Published Date

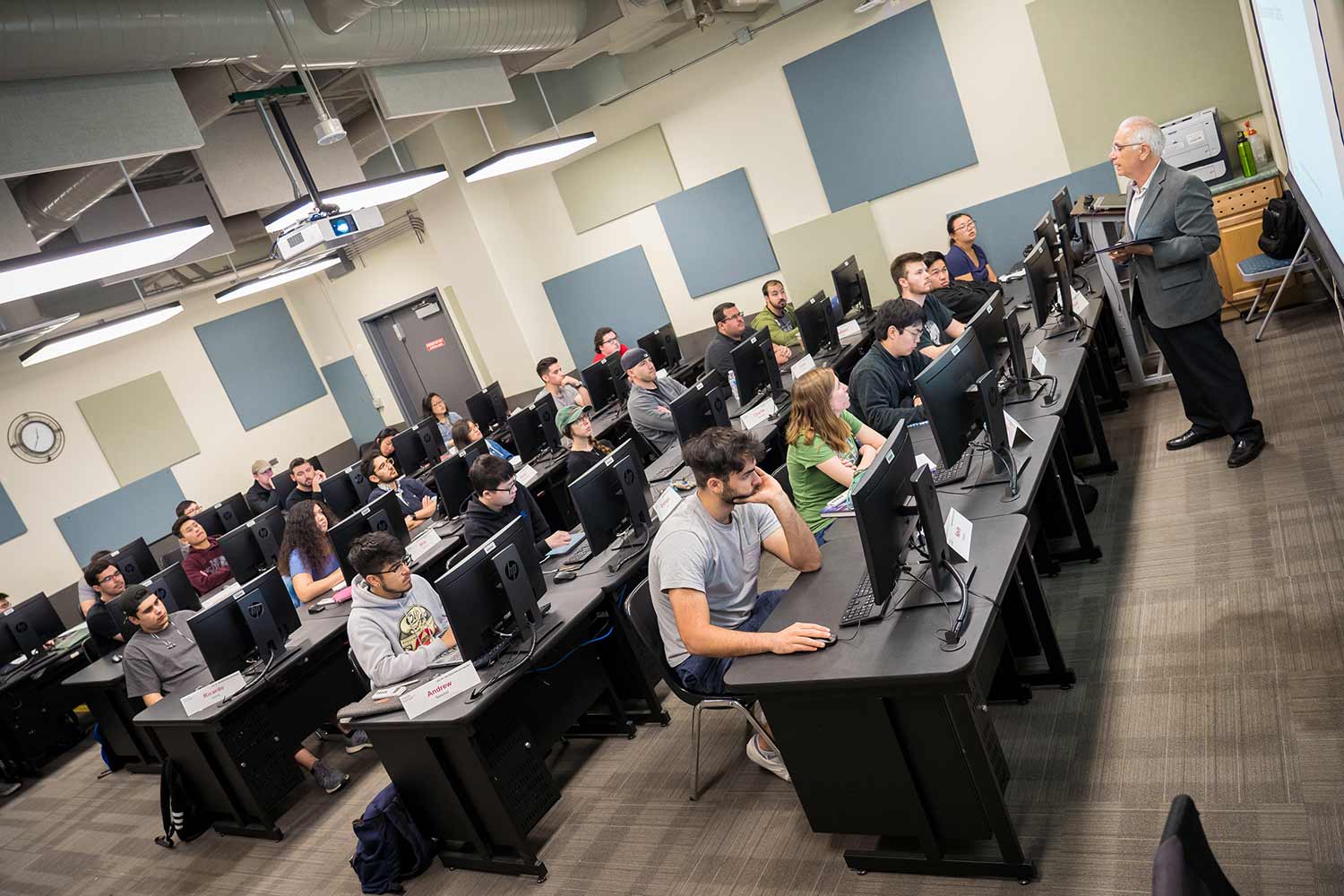

Nicholas Abi-Samra, an energy expert and industry veteran, is teaching a unique class on Power Grid Resiliency for Adverse Conditions here at UC San Diego.

Power Prof

Energy expert shares experiences in one-of-a-kind class

When New York and the Northeastern United States experienced a massive power blackout in August 2003, Nicholas Abi-Samra became the lead investigator trying to determine the disaster’s cause. He was then a senior technical director at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), the not-for-profit think tank for the power industry. One of his responsibilities was to lead investigations into major incidents, which took him around the world, to Italy, South Africa, Brazil, Korea, and Australia—and more.

Today, Abi-Samra brings his expertise and experience to the University of California San Diego, where he is offering a series of classes on power systems in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. This quarter, he is teaching a class on power grid resilience for adverse conditions, a one-of-a-kind-course based on the textbook he authored, which was endorsed by North American Electric Reliability Corporation, the watchdog for utilities in the United States and parts of Canada and Mexico. To Abi-Samra’s knowledge, it’s the only class of its kind to be offered in the United States.

In the past four decades, he served in senior technical and managerial roles at various power industry companies. He was a Westinghouse Fellow and a senior technical executive at EPRI, the highest technical positions at these two companies. Before coming to UC San Diego, he was the senior vice president at DNV-GL, a large international company, where he was responsible for the Americas region.

“I teach because I love it and I want to share what I know with my students,” he said.

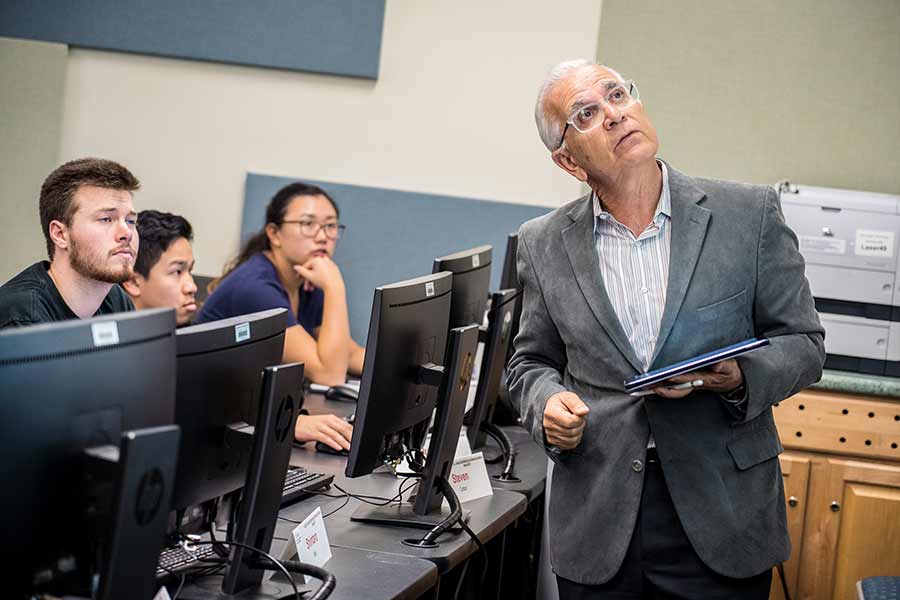

Abi-Samra describes the impact of the 2006 heat wave of California's grid.

In this quarter’s class, students learn about all the different natural and man-made disasters that threaten power grids, from fires, to hurricanes, to droughts to blackouts. The goal is to prepare students for jobs at power companies and research in graduate school. It is part of a series of 12 courses that Abi-Samra developed that examine all the different components of a power grid, from the “generators to toasters”.

“We look at the whole energy chain and what we can do to make it more resilient,” he said.

A number of students who took the class this past year have already been hired at power companies. They also have published and presented research papers.

This quarter, students are talking about the effect of droughts on California’s grid; what happens to grids during floods; and how to prevent grids from being vulnerable to hacking. They say the class has taught them a lot.

Ashley Freeman, an electrical engineering senior who plans to work in industry, said she now has a better understanding of how complex power grids are. “I got a better idea of the big picture,” she said.

Khalid Alrabiah, an electrical engineering senior who plans to go to graduate school, said he appreciates that Abi-Samra shares his industry experience. “He’s more practical and focused on real life,” the student said. “I really like it.”

On a recent Wednesday morning, Abi-Samra walked his students through what happened to the grid during the 2006 heat wave that left 2 million Californians without power in June and July of that year. The heat wave was particularly hard on the grid because it hit both Southern and Northern California roughly at the same time. This made it impossible to transfer energy from one part of the state to the other to meet demand.

During the day, temperatures reached 110 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperatures did fall at night, but not enough to lower demand on the power grid. As a result, hundreds of distribution transformers, which are installed on power poles, or on curb, failed—at the same time—leading to blackouts and brownouts.

One lesson from the 2006 heat wave was that the lifespan of a distribution transformer depends on its loads and temperature, Abi-Samra explained. Before then, distribution transformers were “run to failure”: utilities installed them and left them unattended until they failed. And because California enjoys particularly stable weather, transformers could last for decades without inspections or maintenance—until a catastrophic event causes them to fail. Based on the analysis he did on those failures, he came up with transformer loading models, which are used today to assess the impact of electric vehicles on the transformer.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.