From Lebanon’s Vineyards to Vision Restoration

Growing up in rural Lebanon, tinkering with cars and working the grape harvest gave professor Shadi Dayeh a hands-on foundation that now informs his innovations in brain mapping and potentially vision-restoring whole-eye transplantation.

Published Date

Article Content

Today, Shadi Dayeh is working at the frontiers of medicine and engineering, including on potentially vision-restoring whole-eye transplants. But his earliest explorations weren’t in a lab or lecture hall: it was a sun-baked car repair shop and the sprawling vineyards of his hometown in Lebanon.

“During my teenage years, I worked in car repair shops, and that instilled in me the desire to do something related to engineering," he said. Dayeh, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at University of California San Diego's Jacobs School of Engineering and affiliate of the university’s Qualcomm Institute, explained that the six summers he spent working as a mechanic meant that the principles of physics and experiments came naturally to him years later.

The rest of Dayeh's summers were spent harvesting grapes or selling pistachios by the road, as he’s from a wine-producing town where most of the town kids worked in the vineyards during the summer.

Dayeh grew up in Kefraya, a small mountain village of about 100 homes that overlooks eastern Lebanon's Beqaa Valley. While he pursued physics and electronics during his undergraduate years at the Lebanese University in the country’s capital, Beirut, Dayeh took the leap to the United States to carry on his studies at Southern Methodist University — despite most of his peers pursuing graduate school in France.

At SMU, Dayeh started researching the applications of infrared sensors on flexible materials; his work ultimately brought him to pursue a Ph.D. at UC San Diego.

“I enjoyed collecting information, looking at the missing pieces and talking with key leaders about ways to fill those gaps and solve certain challenges in the field,” he explained, adding that it was challenging, but "when it worked, it was very rewarding."

"I love that process and feeling like I can contribute to something," Dayeh said. "I'm the type of person who gets fully committed to get a project done regardless of the challenges and will put in a lot of overnight work sessions if I need to."

That blend of curiosity, persistence and hands-on experimentation became a hallmark of his approach even after he pivoted from working on circuits to researching semiconductor devices and nanoscale materials for vertical transistor structures, which use quantum mechanical properties to offer unprecedented control over how electronics behave. His work culminated in a series of publications that made him one of the most highly cited researchers in his field.

After earning his Ph.D., Dayeh joined Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2008 for a Director’s postdoctoral fellowship, where he expanded his expertise in silicon germanium heterostructures and nanoscale electronics and realized those structures could be used in neural interfaces. He then became a Distinguished J.R. Oppenheimer Fellow and established his own research group where he co-mentored over half a dozen postdocs — all before taking a faculty position at UC San Diego in 2012.

Bringing nanoscale precision to the brain

Soon after joining UC San Diego, Dayeh’s focus shifted toward neurotechnology. Rather than focusing on nanoscale devices, he pivoted toward recording neuronal signals; within a year, Dayah was in operating rooms recording neural activity from patients during surgery. By the end of 2018, his lab had a breakthrough.

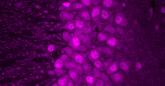

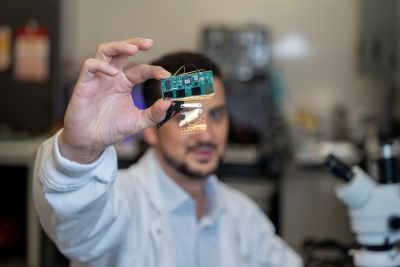

"We figured out how to stack thousands of sensors on the surface of the human brain to read the brain's activity," he explained. Between 2019 and 2021, Dayeh's team recorded activity from 26 patients with 2,048 channels and grids, which allowed him to capture highly granular details about the brain’s electrical activity. By stacking thousands of ultra-thin, flexible sensors, he explained, Dayeh's team could monitor fine-grained signals from each of the brain's cortical columns, or fundamental processing units.

"We have around 150,000 cortical columns in our brain, so we really need tens of thousands of sensors to be able to understand how our brains process information," he said.

The challenge wasn't just technical but also logistical. As the brain is soft and moving all the time, it was tricky to find a way to incorporate electronics in the brain sensors, especially given safety concerns. And, it took seven unsuccessful grant proposals over seven years before he received a major $12.2 million National Institutes of Health (NIH) BRAIN(R) award in 2021 to address this problem adequately.

Now Dayeh leads a large, multi-institutional NIH program on wireless epilepsy monitoring, further underscoring his ability to orchestrate milestone-driven collaborative research.

“The challenging aspect was getting the resources to do this work,” Dayeh said, adding that in the end, it led the team to innovate new solutions by adapting manufacturing techniques from flat-panel displays. Ultimately, the team was able to build sensors that were more sensitive, flexible and capable of long-term use.

“We were forced to think about it a different way, and that led us in a direction the field wasn’t going,” he said. "Everybody had been taking the same approach for 30 to 40 years, and I looked at it from a different perspective."

The Qualcomm Institute (QI) also played a key role in his discoveries. Dayeh’s group relies on QI’s Nano3 fabrication facilities, a hub for advanced micro- and nanoscale device fabrication, for nearly all its work, making his group the largest user of the facility on campus.

“QI is a unique infrastructure at UC San Diego because it’s like a testbed of innovation,” he explained, adding that support from QI leadership, combined with cross-departmental collaboration, has allowed his research to scale from concept to clinical impact.

The clinical implications are significant, as high-resolution grids can not only guide neurosurgeons during procedures, but also enable precise monitoring of epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Dayeh’s technologies achieved U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 2024, a milestone demonstrating regulatory readiness and translation into patient care./p>

Dayeh also noted that the current neural interface project he's working on with clinicians from UC San Diego Health and two other hospitals has been particularly illuminating.

“The clinical input keeps us grounded and helps us better understand patient needs,” Dayeh added, describing himself as a “feedback junkie” who prioritizes going out into the field to see what kinds of solutions will best fit a certain problem.

He also spoke highly of his neurosurgery and neurology colleagues at UC San Diego, saying that he has “some of the best forward-looking neurosurgery and neurology colleagues and leadership that helped to turn dream solutions into a reality.

“We want to make sure that our technologies address the gap we’re trying to fix, and we’re not always right. Sometimes approaches need to be reworked, but that doesn’t mean we made the wrong judgement—it just means we need to pivot toward a better solution and learn from our failures.”

“My lab was built with engineers and neurosurgical residents who share both the credit and the success,” Dayeh said, pointing out that many of these mentees went on to become successful faculty members in various academic departments.

“We want to make sure that our technologies address the gap we’re trying to fix, and we’re not always right,” he added. “Sometimes approaches need to be reworked, but that doesn’t mean we made the wrong judgement—it just means we need to pivot toward a better solution and learn from our failures.”

The optic nerve frontier

Perhaps the most audacious project in Dayeh’s lab isn’t even focused entirely on the brain — it deals with whole-eye transplantation.

In collaboration with Scripps Research, the independent nonprofit research institute down the road from UC San Diego, and with funding from Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), he's helping pioneer whole-eye transplantation>. The goal? Not just to transplant the eye, but also to bring back sight by reconnecting the optic nerve to the visual cortex.

He explained that Dr. Anne Hanneken, an associate professor of translational research at Scripps Research, had shown that it's possible for the eye to be revived within four hours of death if handled a certain way.

Now, he said, "the final frontier is to connect the optic nerve to the brain," and he sees his role as figuring out how to fix that connection.

Already, Dayeh's lab has developed high-density electrode arrays that map the retina’s representation within the optic nerve, which helps to guide reconnections between the organ donor and the recipient. They then apply electrical stimulation to guide axonal regrowth to help form new pathways to the brain.

“There are about 800,000 to a million axons in the optic nerve," Dayeh explained. "It’s extremely compact and complex. But we think we have the technology to break down the challenge piece by piece and deliver the best therapy one can for the treatment of vision disorders.”

He is also the founder of Cortical Science, Inc., a company that’s set to translate his neural interface technologies into commercial products and will draw on both Dayeh’s entrepreneurial skills and his academic achievements.

More broadly speaking, Dayeh sees the next decade of neuroengineering as a fusion of biology and technology where minimally invasive devices, gene therapies and stem cell interventions will complement and eventually integrate with engineered solutions.

“You can use technology to make biology stable on its own and then take the technology back out of the body,” he explained. “That’s what I’d like to work on in the next phase of my career: I want to merge my neurotech work with biologics to figure out how we can better integrate tech and biology to treat patients with neurological diseases and disorders.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.