Study Finds Pattern in DDT Contamination Among Fish off Southern California

The findings could help predict fish toxin levels and inform fish consumption advisories

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Share This:

Article Content

The toxic pesticide DDT was dumped into the ocean off Southern California more than 50 years ago by the Montrose Chemical Corporation, and it is still contaminating fish and sediments in the region decades later, according to researchers. Banned in 1972, the pesticide is now known to harm human and wildlife health, with prior research linking it to cancer as well as reproductive and neurological issues.

UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography is one of numerous institutions exploring the extent of the environmental damage still being caused by DDT contamination, especially at a series of offshore dumpsites that gained public attention in 2020.

Now, new research led by Scripps Oceanography combines nine different datasets spanning two decades to provide a comprehensive look at DDT contamination in Southern California’s ocean sediments and fishes. The study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Science Foundation, revealed new patterns and some good news.

The team found that DDT concentrations in ocean sediments were highest close to known dumpsites, suggesting the contaminated sediments have mostly stayed put. Fishes from locations where the underlying seafloor had higher levels of DDT also tended to contain higher concentrations of the pesticide. But the strength of this relationship between sediment and fish DDT levels also varied in predictable ways depending on a given fish’s habitat and diet.

Researchers say the good news is that DDT contamination in fish has decreased over time and the vast majority of recreationally caught fish in the region were safe to eat — meaning they were below the threshold used to create California's consumption guidelines. Notable exceptions include bottom-dwelling fish such as halibut caught near the most contaminated sites, such as the Palos Verdes Shelf superfund site. Recreational anglers remain cautioned to consult relevant consumption advisories to ensure their catch is safe to eat.

By revealing robust relationships between DDT levels in fishes and their habitat, diet and location, researchers said the study will lead to more accurate, location-specific fish consumption advisories.

“I was surprised by how strong the relationship was,” said Lillian McGill, lead study author and a postdoctoral researcher at Scripps, “strong enough to reasonably predict DDT concentrations in a fish based on where it was caught and its diet and habitat.”

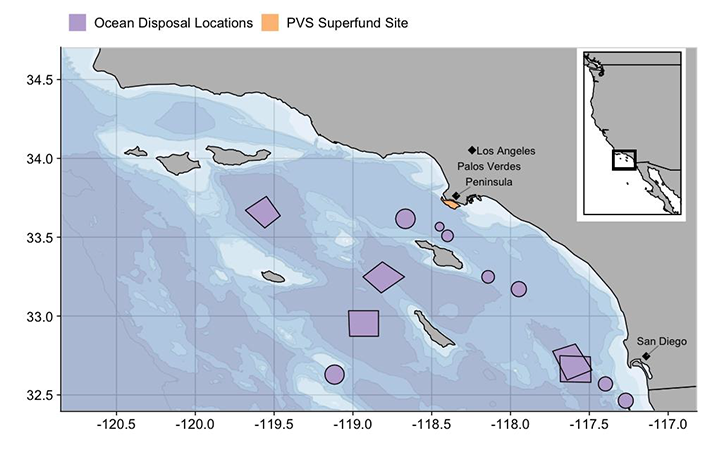

The Palos Verdes Shelf superfund site (orange shaded area) and 13 known deep ocean disposal locations (purple shaded areas) for DDT manufacturing waste. Credit: McGill et al 2024

Various agencies and research groups have been measuring DDT contamination in fish and sediments off Southern California for decades. Beginning in 2023, McGill and her co-authors sought to compile those data to get a better big-picture understanding of DDT contamination and to find out how it changed through time. The researchers also wanted to explore potential connections between contamination levels in fish and ecological factors including the fish’s location, habitat preferences and diet.

Some of the key data sources were the Southern California Bight Regional Monitoring Program, the Coastal Fish Contamination Program, the Statewide Coastal Screening Survey, the City of San Diego Ocean Monitoring Program and the Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts Local Trends Assessment.

“There was actually a lot of information out there on DDT in fish and sediments, but it wasn’t easily accessible,” said Toni Sleugh, study co-author and a PhD candidate at Scripps. “Combining the datasets makes them more powerful, and it might be comforting for the public to know that these monitoring efforts have been happening for some time and they’re pretty comprehensive.”

The compilation included nine datasets spanning 60 fish species from across the Southern California Bight from 1998 through 2021. First, the team analyzed the DDT concentrations in ocean sediments and fish. Next, the researchers used statistical models to tease apart the relationships between DDT’s distribution in sediments and contamination levels in fish as they related to the fish’s location, diet and habitat.

The study found the highest DDT concentrations in ocean sediments at the original dumping locations, even after half a century. Fish DDT levels generally reflected the degree of sediment contamination from where the fish were collected, but the strength of the relationship depended on the fish’s habitat and diet.

Sediment DDT levels were most strongly tied to fish contamination for species that lived near the bottom. Sediment contamination, however, was not as good a predictor for fishes that lived closer to the surface or for fishes higher in the food chain, which each had relatively consistent DDT levels across locations.

According to the researchers, these findings demonstrate the persistence of certain chemical pollutants in the ocean, while also showing that the remaining hazards from DDT in Southern California appear to be relatively localized and follow a generalizable pattern.

“If DDT contamination is moving through the ocean in predictable ways, then we can mitigate our exposure while still making use of the ocean,” said Brice Semmens, Scripps Oceanography marine biologist and co-author of the study.

Overall, DDT levels in fish decreased between 1998 and 2021.

“The jury is still out, but I think one of main reasons for the decrease is that the contaminated sediment is slowly being buried by new sediment,” said Semmens. “This could be why we are seeing less in the food web over time.”

Though the vast majority of fishes in the study did not contain levels of DDT contamination that exceeded California’s guidelines for human consumption, Semmens pointed out that the study’s samples focused on fish and sediment contamination near shore, and can’t directly speak to deep water dumpsites farther offshore that came to light in 2020.

“It remains to be seen whether DDT from these deep dumping sites is more problematic than what our results reflect,” said Semmens. “Researchers from Scripps and other Southern California research institutions are currently working on this question.”

The researchers have used their findings to create a framework for predicting contamination in individual fish based on sediment data near the location where the fish was caught and information about the ecology of the species, even for species not included in the present study.

The researchers are collaborating with students in UC Santa Barbara’s Masters of Environmental Data Science program to develop a user-friendly website where anglers can input their catch details and receive information about anticipated DDT contamination and consumption guidelines. A beta version of the site, called SaferSeafood, is now up and running. The website aims to improve the accuracy of consumption advisories, which could benefit vulnerable communities that rely on fishing for food.

A follow-up study led by Sleugh is currently underway to measure present concentrations of DDT in a range of Southern California fishes. The study will include additional measurements such as fish age and diet that were not included in previous datasets but that might prove to be important factors in an individual fish’s level of contamination.

In addition to McGill, Sleugh and Semmens, Colleen Petrik and Lihini Aluwihare of Scripps as well as Kenneth Schiff and Karen McLaughlin of the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project co-authored the study.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.