The Long Road to the Sandbox: An Unlikely Journey to a World-Class Technology Hub

School of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor Uri Manor overcame the challenges of a disability that caused social neglect and other obstacles on the way to leading UC San Diego’s new high-tech cluster

Story by:

Published Date

Article Content

When the Goeddel Family Technology Sandbox opens its doors on the UC San Diego campus on August 29, the cutting-edge facility will immediately take its place as a unique world-class resource for science, education and training. A gathering point for top-flight scientific instruments, the Technology Sandbox also is a nexus for partnerships with the life sciences industry, including Thermo Fisher Scientific and Nikon Instruments.

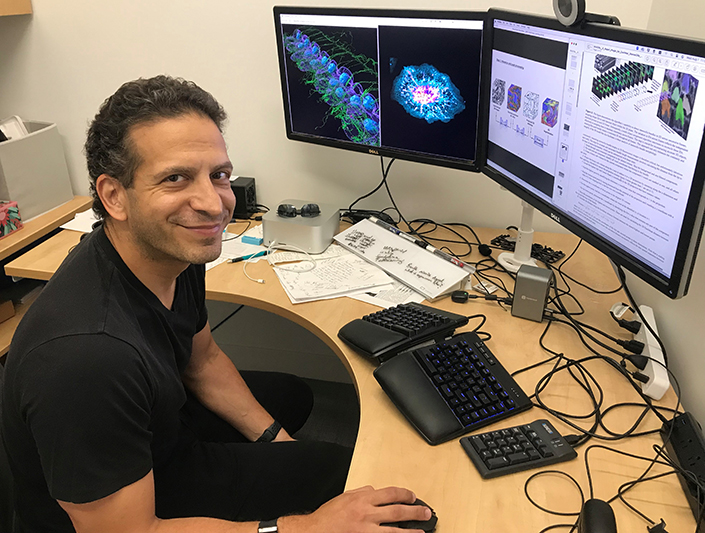

The inaugural faculty member charged with leading the new facility comes to UC San Diego with an extraordinary background. School of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor Uri Manor’s journey to the Goeddel Family Technology Sandbox is a winding path filled with challenges, including a hearing disability that sometimes led to bullying, social neglect and educational hurdles. Now he has flipped the script. It’s his turn to invite others to join him in the Sandbox to play with science’s most advanced “toys.”

Did you always know you were going to be a scientist?

I definitely did not know. I was born with severe-to-profound hearing loss. As there was not routine newborn hearing tests performed at that time, my family did not know I was hearing impaired until I was almost two years old. Growing up, I was horrified that my disability meant I was perceived as “abnormal,” so I made every effort to deny my disability. Because I often didn’t understand what was said in conversations or in the classroom, I was mocked and perceived as less intelligent by many of my classmates. I just never felt like I fit in. I wasn’t really invited to hang out with anyone and in many cases I was bullied because I was so different from most of my classmates — I wore hearing aids, I had a strange name, much darker skin, etc.

Thankfully, I transformed my insecure energy and desire to prove myself into a productive lifestyle with a huge passion and love for my scientific work. Providing the scientific community with cutting-edge scientific tools and discoveries has enabled me to prove to myself that I was never as dumb as my bullies claimed. By helping humankind through my work, I am proof that people with disabilities are just as valuable and can contribute as much as anyone else.

Tell us about your road through education?

I was really bored in the classroom as a child, almost certainly exacerbated by some combination of my hearing loss and ADHD. It took so much effort to understand what the teacher was saying that it was exhausting. The content wasn’t interesting to me either so I didn’t really enjoy school and I wasn’t a good student. When I was very young I wanted to be a baseball player. I grew out of that by the time I hit 12 then I really got into guitar and I thought I could be a musician, which is also kind of ironic because of my hearing loss. Then again, one of my guitar heroes, Paul Gilbert (of Mr. Big fame), also has hearing loss, so who knows? Either way, I suffered from massive depression and couldn’t focus at school and dropped out almost immediately from college. I worked in the restaurant business for a few years, starting as a busboy and expeditor, then eventually as a waiter and bartender, working 12-hour double-shifts six days a week.

How did you return to academia?

At some point I became really interested in magnetoreception, which is how animals navigate using Earth’s magnetic fields. I thought it would be cool to learn physics, and use physics to understand biology. I started attending St. Louis Community College, taking classes during the day and working night shifts in the restaurant. At that point I was much more engaged in my learning and so I was suddenly getting straight As, then transferred to a four-year university.

You completed graduate studies with Dr. Bechara Kachar at Johns Hopkins University and postdoctoral work in the Lippincott-Schwartz lab at the National Institutes of Health. How did these experiences shape your research interests?

Dr. Kachar invited me to come to his lab and started showing me beautiful electron and fluorescence microscope images of the sensory hairs of the inner ear, of which I had never seen real images, even though I had seen cartoons of the cochlea in audiologists’ offices hundreds of times before. These microscope images blew me away. I simultaneously fell in love with microscopy imaging as an art and also the inner ear sensory hair cell as a system. Maybe I was biased by my hearing loss. You don’t have to have hearing loss to appreciate it, but maybe there was a tiny bit of this feeling of destiny that I had suddenly somehow ended up with an opportunity to work on hearing, completely unexpectedly. Today I continue to do work on the inner ear and stereocilia, the hairs of the inner ear, which are skeleton-based structures. I now am also interested in the synapses of the inner ear, which are a major target for age-related hearing loss.

Within my lab I’ve personally realized that hearing loss research is of particular interest to people with hearing loss, who are one of the most underrepresented populations in STEM. I’m actively recruiting people with hearing loss to come work in my lab — soon we will have an incredibly talented undergraduate student with hearing loss joining the lab and I could not be more excited.

By helping humankind through my work, I am proof that people with disabilities are just as valuable and can contribute as much as anyone else.

With your interest and experience in advanced scientific instruments, you oversaw a technology core at the Salk Institute and now you are serving as faculty director of the Goeddel Family Technology Sandbox. What’s behind your interest in these technology clusters?

The Technology Sandbox is truly one of a kind in that it has multiple kinds of research technologies from traditionally separate disciplines. This is the only center in the world that has all these technologies together under one roof with the experts to go with them. Everything from neuroscience to plant biology to bacterial cell biology are all going to be propelled forward by having access to these technologies. It’s hard to predict exactly what will happen because it’s really never been done before, but I’m sure it will be beautiful.

My fantasy is to build models that start at the atomic level and then go all the way up to the macromolecules, cells and tissues of an organism. I’m really attracted to the idea of having a single center where you’re going to have the capability of mapping the atomic structure, then the cellular organization and even the dynamics of the same or similar samples in one place.

What drew you to UC San Diego and the Sandbox?

One of the things I’m excited about with the Sandbox is being able to play a role in helping orchestrate the collection and curation of different data sets in a way that’s amenable to machine learning to obtain new biological insights.

From the microscopy end we’ve figured out that deep learning is really the future of processing and analyzing large sets of microscopy data. Ultimately machine learning (aka “artificial intelligence”) is exponentially more powerful than other methods we used in the past. The Technology Sandbox is going to be a way for all the biologists to get together and bring different kinds of data from various kinds of samples, contexts, conditions and preparations. All these data can and will be used to feed ever larger and more powerful models that we plan to release to the wider scientific community as open source tools for research.

Education and training are also very close to my heart. That’s another big reason why I was excited to move to UC San Diego, to work more closely with students and do more teaching. The Sandbox is going to be an amazing resource for students to be able to be exposed to cutting-edge tools and data analysis.

What career advice do you have for those with disabilities?

One of the big things that hits people with hearing loss and probably anyone with a disability is imposter syndrome. I encourage anyone who is struggling because of their disabilities or other types of challenges to not forget that everything you’ve accomplished is in spite of your challenges.

In some ways you have strengths that others around you don’t have. That actually gives you an edge and it means that you can do things that others can’t. Try to invert that imposter syndrome and realize that you have a really unique perspective and strength, whether that’s fair or not, because you had to deal with those extra burdens and you continually deal with them.

At the same time, it is important to realize that just because some people can be unhelpful or even hostile, they are the minority. Most people are good and want to help each other, and sometimes what feels like a big ask or favor is actually a really easy opportunity for someone to feel helpful and supportive. Long story short, do not be afraid to ask for help when you need it! I suffered needless difficulties for years because I was too shy to ask for accommodations and I am grateful that today most people recognize the value of supporting those who are different.

The Technology Sandbox is truly one of a kind in that it has multiple kinds of research technologies from traditionally separate disciplines. This is the only center in the world that has all these technologies together under one roof with the experts to go with them.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.