Scientists Locate Brain Area Where Value Decisions Are Made

Data from mouse neurons point to unexpected brain region, carrying implications for health and disease

Published Date

By:

- Mario Aguilera

Share This:

Article Content

Neurobiologists at the University of California San Diego have pinpointed the brain area responsible for value decisions that are made based on past experiences.

Senior author Takaki Komiyama says data from tens of thousands of neurons revealed an area of the brain called the retrosplenial cortex, or RSC, which was not previously known for “value-based decision-making,” a fundamental animal behavior that is impaired in neurological conditions ranging from schizophrenia to dementia and addiction.

Such decision-making is not the kind we encounter, for example, when navigating traffic lights, which are external cues that dictate our car-driving decisions. Rather, Komiyama, lead author Ryoma Hattori and their colleagues found that the RSC is the home region for decisions such as where we buy our morning coffee. When we visit a coffee shop, our subjective value of the shop is updated based on our experience in the RSC where the value is maintained until the next time we go out for coffee.

The research is published May 9 in the journal Cell.

“When you have two coffee shops to choose from, no one is telling you which one to go to—you rely on the internal value in order to choose one over the other,” said Komiyama, a neurosciences professor in UC San Diego’s Division of Biological Sciences and School of Medicine, and a founding faculty affiliate of the Halıcıoğlu Data Science Institute. “How the brain maintains this value information—and how it might be different in healthy and disease states—could be relevant in clinical applications.”

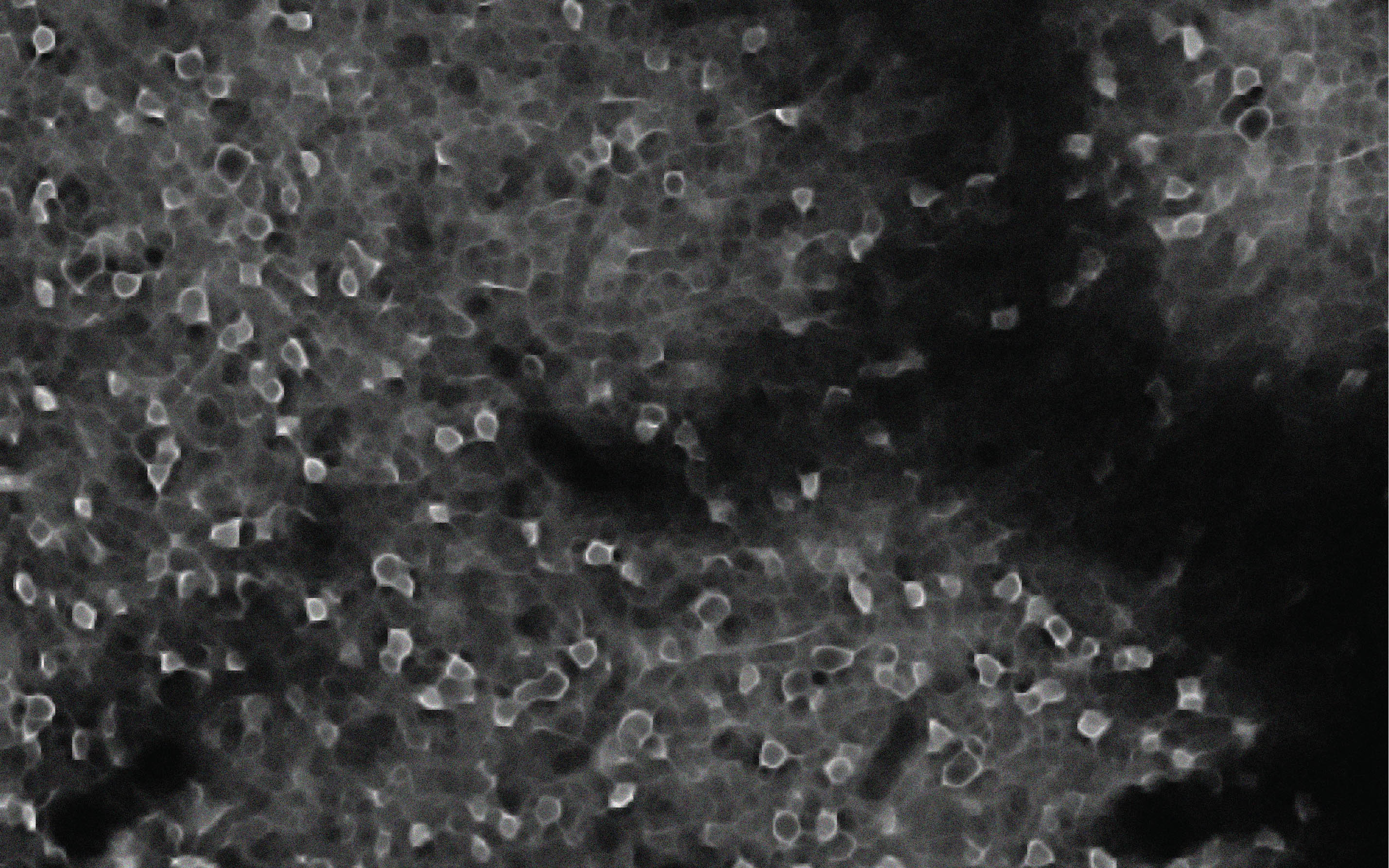

The research team simultaneously imaged more than 500 neurons across six brain regions in mice. The resulting data trove of more than 45,000 recordings allowed them to compare how value-related information is processed in each brain area. This vast data set led them to the RSC, an area in the outer layer of the cerebrum known as the cortex, which connects a range of brain networks and functions.

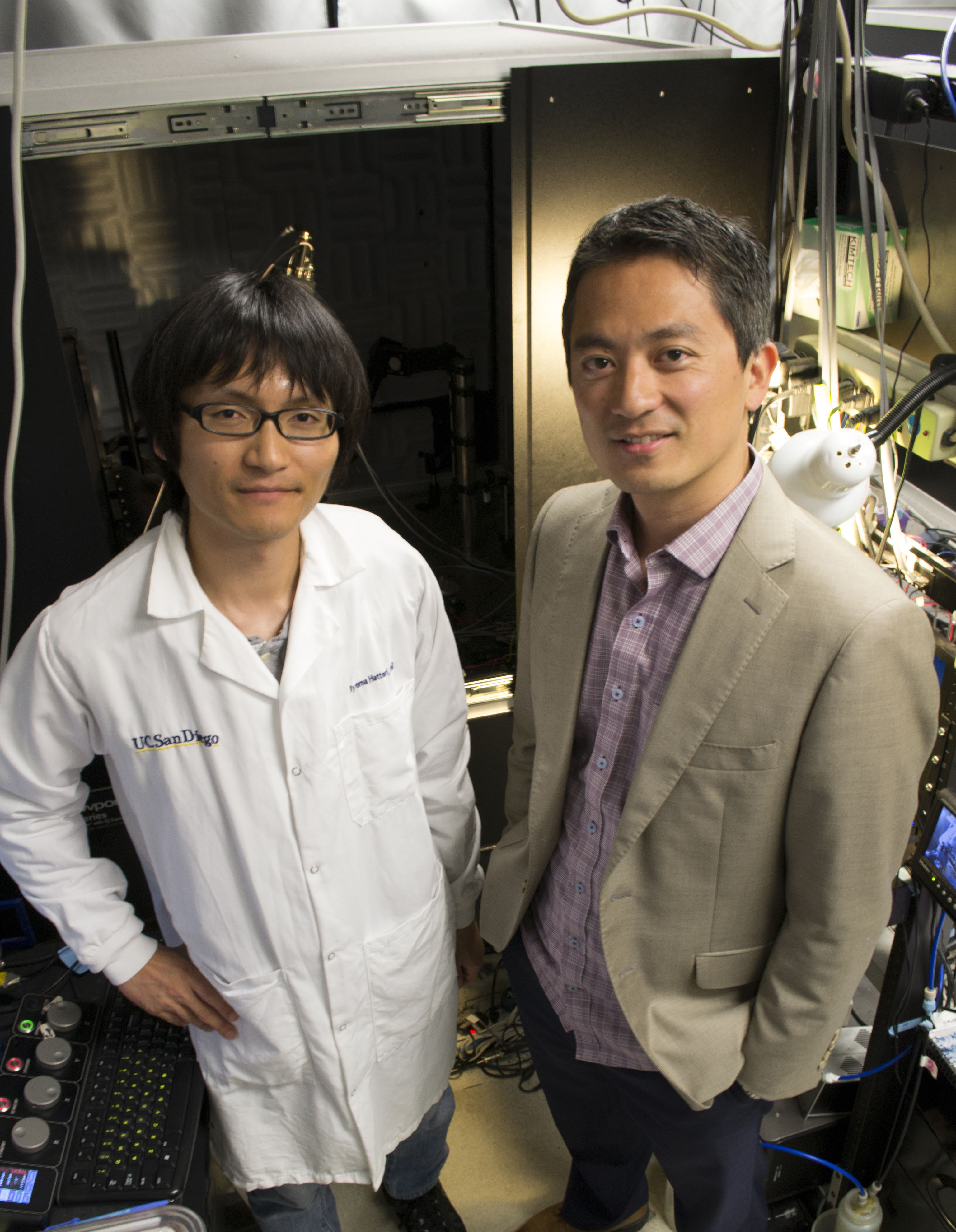

Ryoma Hattori (left) and Takaki Komiyama.

“We found that the RSC, which previously had not been studied in the context of value-based decision-making, showed the strongest value information most persistently over time. These were unique characteristics,” said Komiyama.

To confirm whether the value information in RSC is used for decision making, the researchers inactivated the RSC using a technique called optogenetics, which uses light-activatable proteins to manipulate neural activity. Results showed that these mice did not remember what happened in previous experiences.

“Basically, we made the mice forget the recent history by inactivating this particular RSC area,” said Hattori.

The researchers are now studying how the RSC interacts with other brain systems to establish and maintain value-based activity patterns.

Komiyama, whose lab generates nearly a terabyte of data per day, says science’s recent capacity to record and study massive data sets opens new windows to our understanding of basic neurological functions.

“Previously these types of experiments were with one neuron at a time, which was simple to analyze,” said Komiyama. “Technological advances are allowing new experiments with thousands and thousands of recordings of neuronal activity that can be related to various features of behavior. I’m sure we’re still just scratching the surface of these complex data so the next new challenge has become big data analysis.”

Coauthors of the study in the Komiyama Laboratory included Bethanny Danskin, Zeljana Babic and Nicole Mlynaryk of UC San Diego’s Division of Biological Sciences Section of Neurobiology, the Center for Neural Circuits and Behavior and the Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS091010A, R01 EY025349, R01 DC014690, U01 NS094342 and P30EY022589), Pew Charitable Trusts, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, McKnight Foundation, New York Stem Cell Foundation, Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind and the National Science Foundation (1734940).

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.