By:

- Brittany Hook

Published Date

By:

- Brittany Hook

Share This:

Giving the Ice a Voice

Composer Brings Sounds of Antarctic Ice Shelves to Life with Help of Scripps Researcher

Composer Glenn McClure listens to the ice on the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. “I placed my ear to the sea ice and I could hear not only the ice cracking and moving, but I could also hear seals talking to each other underneath,” said McClure. Photo by Glenn McClure.

Deep within the ice shelves of Antarctica, there are stories—and musical compositions—to be told.

Composer Glenn McClure recently teamed up with researchers at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Birch Aquarium at Scripps to transform Antarctic ice shelf vibrations into unique musical arrangements.

“What I want to do is to give a voice to the ice,” said McClure, a faculty member at SUNY Geneseo and Eastman School of Music.

McClure received a National Science Foundation Artists and Writers Fellowship for the project, called “Music in the Ice,” which led him on a 40-day expedition to Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf. There he worked closely with a scientific team led by Scripps researcher Peter Bromirski.

Bromirski and other scientists are interested in the 800-kilometer (500-mile) wide Ross Ice Shelf as it’s the largest in the Antarctic and a region destined to be greatly impacted by the effects of climate change. The front of the Ross Ice Shelf is directly impacted by ocean waves, which send vibrations throughout it. Similar to how a beating heart sends a pulse throughout the body, ice shelf vibrations can be used to help assess the health—the structural integrity—of the ice shelf.

In 2014, Bromirski and colleagues deployed an array of broadband seismometers on the ice shelf surface to measure the amplitude and speed of these vibrations. McClure assisted the research team with the retrieval of the seismometers in the austral summer (October to December) of 2016.

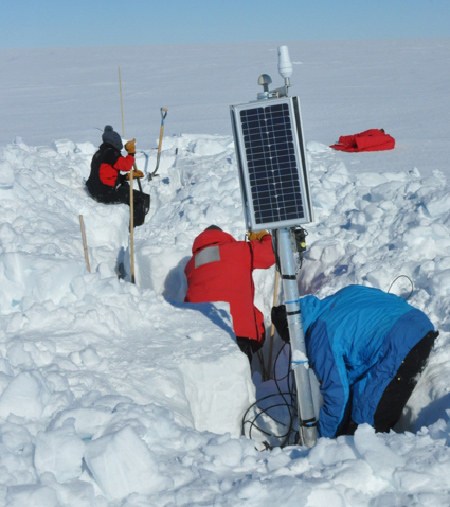

The Scripps-led research team retrieves a seismometer from the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Photo by Glenn McClure.

He is now using modular mathematics to translate the data collected from the seismometers into symphonic works. The resulting musical compositions from McClure’s project will be incorporated into the second phase of a new immersive exhibit at Birch Aquarium at Scripps, entitled The Expedition, which will likely open sometime early next fall.

The work is deeply personal for McClure, who is afflicted with severe stutter but has learned ways to control his disability through music.

“The only time I could open my mouth without the physical and the emotional stress of a disability was when I sang because music circumnavigates the brain of a stutterer,” said McClure, recalling the struggle he went through as a child. “Stuttering was something that silenced me but music gave me a voice, so now I want to give that same voice to the silence of the ice.”

McClure contacted Bromirski after learning about his research on ice shelf vibrations, and after several discussions, the two decided to collaborate.

“I’m very confident that Glenn’s transformation of the Ross Ice Shelf seismic data to a musical composition will produce an excellent symphonic work,” said Bromirski, a researcher in the Integrative Oceanography Division at Scripps. “His plan to present his composition at a variety of venues as orchestral and choral work will further the awareness of my project and, hopefully, draw attention to the importance of Antarctica’s ice shelves to sea level rise resulting from global warming.”

In addition to hosting live musical performances featuring McClure’s work, the aquarium plans to use some of his photographs, videos, and audio clips from Antarctica for part of a forthcoming polar exhibit called “Footprints in the Snow.” This exhibit will highlight Bromirski’s ice shelf research and will connect aquarium visitors to science at Scripps.

“When you’re trying to translate complex science to general audiences, you don’t want to start with a lot of text. So the way that we’re approaching connecting our science to public visitors is by creating these immersive experiences that are compelling and strike all of your senses,” said Harry Helling, executive director of Birch Aquarium at Scripps. “Once we get you interested and hooked, then we can start getting you more interested in asking your own questions about the nature of science and how it works. We think that leads to a better learning cycle for people to understand both our science and their place on the planet.”

Scientific divers investigate the underwater world below the seasonal sea ice near McMurdo station. Composer Glenn McClure also takes in the view from an underwater observation tank. Photo by US Antarctica Program/NSF.

Visitors to the new exhibit will be able to see seismic instrumentation used by Scripps scientists, view recorded footage of incoming Antarctic storms using virtual reality, and hear crunching sounds from footprints in the snow—as recorded by McClure—with each step they take inside the space.

“It’s very authentic; every time you hear that sound, it is real, and it was collected by an artist in Antarctica,” said Helling. “We’re using new technologies and art to immerse people in science and connect them to this cutting-edge research.”

McClure’s “home base” in Antarctica was on Ross Island at McMurdo station, a science and research facility that houses up to 900 people. He was surprised by the amount of music and art that happens at McMurdo station.

“There was live music all the time,” said McClure, noting that on any given night, there were up to three venues featuring live music. “In the ways that we often think of the sciences and the arts as being these separate things, it just simply isn’t true in McMurdo, because it is a vibrant artistic community.”

He spent a week camping on the Ross Ice Shelf at an isolated deep-field site called Yesterday Camp—appropriately named because the camp is located near the International Date Line, so the clock-time is a day earlier than McMurdo. Yesterday Camp was the central base for McClure and the Scripps-led research team as they spent their days digging seismometers and GPS instruments out of the ice—hard work that involved lots of shoveling.

Glenn McClure in an observation tank below the seasonal sea ice near McMurdo station. Photo by US Antarctica Program/NSF.

There aren’t any geographic markers to figure out which direction one is facing at Yesterday Camp, and McClure described the experience as disorienting.

“The sun does a circle in the sky, so you never really know what time it is if you don’t have a watch on. When the snow blows or the fog comes in, you can’t even see the horizon anymore, so you can’t tell where the land stops and the sky begins,” he said.

Despite the sense of disorientation, McClure said he found the overall experience to be quite liberating and that it changed the ways in which he views the world.

“I think the most important quality of Antarctica’s beauty is its starkness, the way that it strips away frivolous things and sort of takes beauty down to its most basic form,” said McClure. “The ice and the cold and the mission all have this quality of distilling down those things that are most important in any moment of the day.”

McClure is thrilled to have been given the opportunity to cross-collaborate with Scripps on this project in which he’s pushing traditional boundaries in efforts to fuse science with art. He is greatly looking forward to showcasing this innovative work at Birch Aquarium and across other platforms.

“I hope these musical compositions will allow a very broad audience to get excited about the material,” said McClure. “I think the more that we can help Antarctica tell its story, the better we all will be.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.