Breaking Down Barriers: What Happens When the Vaginal Microbiome Attacks

UC San Diego study begins to explain why a common and seemingly benign condition of the vaginal microbiome is linked to pregnancy loss, preterm birth and other health complications

Story by:

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

Bacterial vaginosis is a common condition in which the natural microbiome of the vagina falls out of balance, sometimes leading to complications in sexual and reproductive health. But exactly how these bacterial populations disrupt vaginal health has remained unclear.

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine have now found that in bacterial vaginosis, certain bacterial species dismantle protective molecules on the surface of the cells lining the vagina, dysregulating key processes that mediate cell turnover, death and response to surrounding bacteria.

The findings, published November 29, 2023 in Science Translational Medicine, may help explain why bacterial vaginosis is associated with many adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes — a longstanding mystery in gynecology.

“The balance of bacteria in the vagina play a key role in a person’s health,” said co-corresponding author Warren G. Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “Bacterial vaginosis is known to be linked to pregnancy loss, preterm birth, postsurgical infections, pelvic inflammatory disease and sexually transmitted infections.”

Bacterial vaginosis is one of the most common vaginal conditions among women of reproductive age. The CDC estimates that in the United States, bacterial vaginosis affects approximately 29% of women between the ages of 14 and 49. While the condition is associated with higher risks of many health complications, it does not always cause noticeable symptoms on its own.

“Even when bacterial vaginosis is identified and treated with antibiotics, recurrences occur in most individuals within a year,” said Lewis.

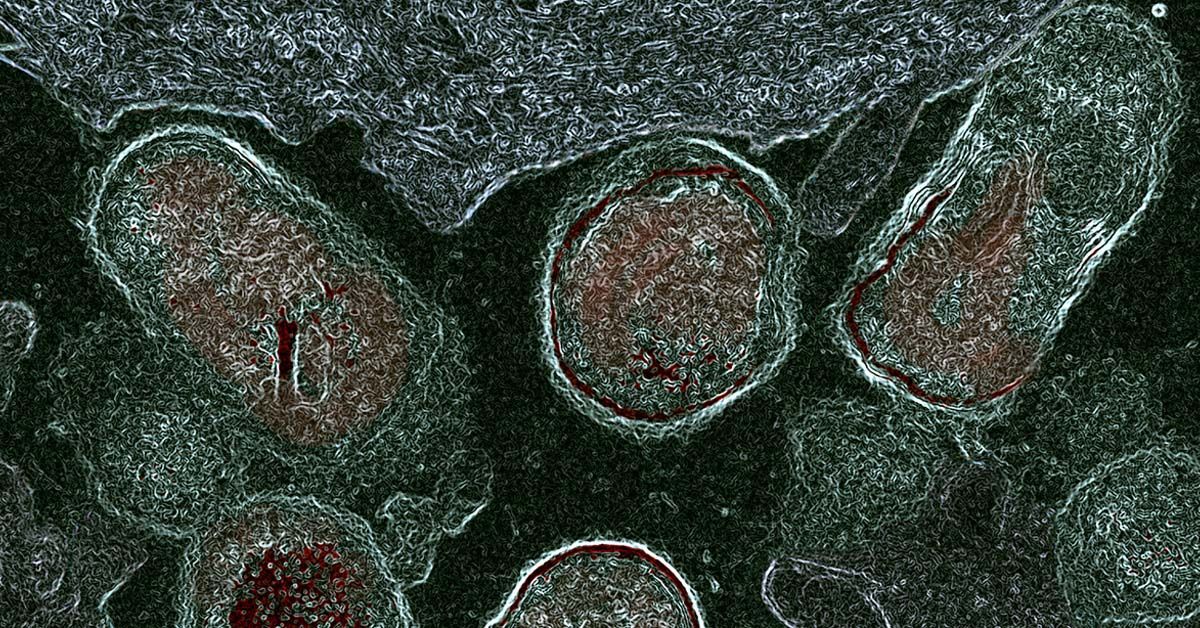

To understand how these bacteria impact vaginal health, the researchers studied the epithelial cells that line the vagina. Because the surface of epithelial cells comes into contact with bacteria and other microbes, it is densely coated with sugar chains, called glycans. Glycans play key roles in cell biology and disease, such as protecting against microbial invasion and helping cells adhere to each other. However, glycans can also be a food source for bacteria.

“We knew that bacterial species implicated in bacterial vaginosis can feed on glycans in secreted mucus. The current study allowed us to look directly at what those bacteria are then doing to the vaginal epithelial surface landscape on a biochemical and microscopic level,” said co-corresponding author Amanda Lewis, PhD, professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

The researchers obtained epithelial cells derived from human vaginal specimens and used them to explore glycan dynamics. With a combination of biochemistry and microscopy techniques, they discovered that in bacterial vaginosis, bacteria release enzymes called sialidases that partially dismantle protective glycan molecules on the surface of epithelial cells. The researchers were also able to induce a bacterial-vaginosis-like state in ‘normal’ epithelial cells by treating them directly with sialidase enzymes produced in the laboratory.

“The fact that we were able to replicate some of the effects of bacterial vaginosis suggests that we may be on the right track to finding a common cellular origin for the various complications associated with this condition,” said Amanda Lewis.

Studying the surface of vaginal epithelial cells at this level of biochemical detail could help make diagnosing bacterial vaginosis easier. The authors suggest differences in glycosylation patterns could also help identify subsets of people with the condition who may be at the greatest risk for negative health outcomes, including recurrence.

“We now have a blueprint of the glycans present on epithelial cells in the vagina, and we showed that these glycans are shaped by the bacteria that live there,” said Warren Lewis. “However, it will take more work to fully understand the functions of glycans in the vaginal epithelium and how bacterial vaginosis impacts those functions.”

As research on the mechanisms of bacterial vaginosis continue, clinicians urge people with vaginas to familiarize themselves with the symptoms of bacterial vaginosis and avoid douching or using scented products, which could result in further microbial imbalances.

Co-authors include: Kavita Agarwal, Biswa Choudhury, Sydney R. Morrill, Daisy Chilin-Fuentes, Sara B. Rosenthal, Kathleen M. Fisch at UC San Diego, Lloyd S. Robinson at University of Washington School of Medicine, Yasmine Bouchibiti and Carlito B. Lebrilla at University of California Davis, Jenifer E. Allsworth at the University of Missouri, and Jeffrey F. Peipert at Indiana University School of Medicine.

This study was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AI114635, R01 AI127554 and UL1TR001442), the Burrroughs Wellcome Fund Preterm Birth Initiative and the University of California through the UC Glycosciences Consortium for Women’s Health.

“The fact that were able to replicate some of the effects of bacterial vaginosis suggests that we may be on the right track to finding a common cellular origin for the various complications associated with this condition.”

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.