Atmospheric River Reconnaissance Flights Begin

On the heels of an exceptionally wet year, an expanded data collection program using Air Force and NOAA aircraft will begin flights over the Pacific from November through March

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Share This:

Article Content

Seven atmospheric rivers classified as strong or greater dumped rain and snow on California during the 2022-2023 rainy season, lifting the majority of the state out of drought conditions and causing disastrous flooding. This duality of promise and peril typifies atmospheric rivers, which are ribbons of water vapor in the sky that can deliver massive amounts of precipitation, and makes accurate forecasting essential to both water managers and public safety officials.

To better understand and forecast atmospheric rivers, “Hurricane Hunter” aircraft from the U.S. Air Force Reserve 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron have begun flights over the Pacific Ocean starting this November as part of Atmospheric River Reconnaissance program (AR Recon), led by the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The program represents a research and operations partnership between science and operational weather forecasting, which ensures that methods and their impacts are continually refined and improved over time.

This year, AR Recon is taking the first step toward expanding its reach farther west across the Pacific by testing flight operations from Guam for a two-week period. This adds to the Air Force aircraft stationed in California and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Gulfstream IV (G-IV) jet stationed in Hawaii, which could facilitate even earlier warnings of incoming severe rain and snowfall. The 2023-2024 campaign also features a longer season of potential flights, new sensors aboard the aircraft, and the deployment of more than 80 additional drifting ocean buoys.

"The AR Recon partnership is a great example of state, federal, and academic collaborative research using emerging technologies to improve California's ability to manage water with increasing weather extremes,” said Michael Anderson, state climatologist with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). “This critical research allows for DWR to use new innovative strategies for water management in a changing climate."

The opening November window for forays into the skies over the Pacific comes as the traditional rainy season begins and with El Niño conditions in the Pacific Ocean, which can create a more active North Pacific storm track and steer more storms towards Southern California.

Despite the importance of accurately forecasting where atmospheric rivers will make landfall and how strong they will be, doing so is challenging with traditional sources of meteorological data such as weather satellites, which often cannot measure the key patterns of water vapor, wind, and temperature within atmospheric rivers.

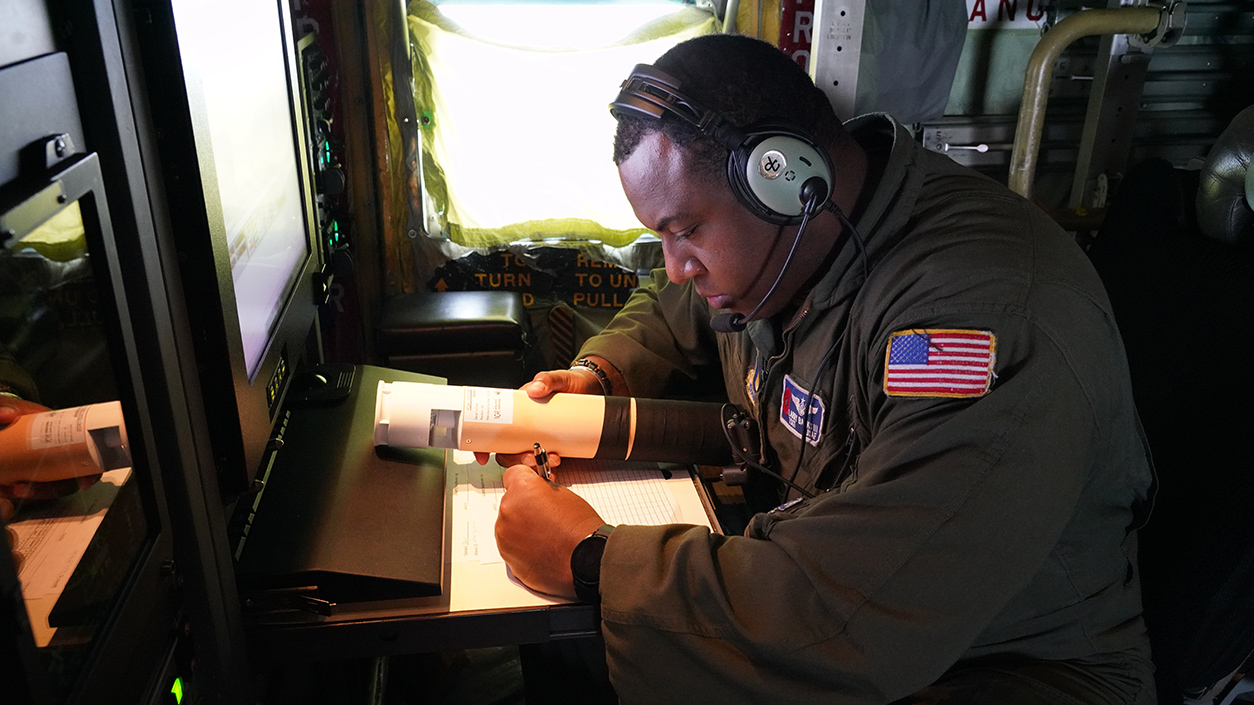

Credit: Senior Master Sgt. Jessica Kendziorek/U.S. Air Force.

“If you want to predict where a car is going to be five minutes from now you need to know where it’s starting from and how fast it’s moving,” said Marty Ralph, a research meteorologist at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and founding director of Scripps’ Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E). “Similarly, if there is an atmospheric river out near Hawaii, and we want to forecast where it will hit the California coast a few days later and how strong it is, we need to get out there and take direct measurements.”

Ralph leads the AR Recon program along with Vijay Tallapragada, Senior Scientist at NOAA’s Environmental Modeling Center. The program’s partners include the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the California Department of Water Resources, NOAA Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, and the U.S. Air Force Reserve 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron.

"Data collected by NOAA’s G-IV and the U.S. Air Force’s WC-130’s during an unprecedented series of ARs in January 2023 contributed to more than 10% improvement in National Weather Service (NWS) Global Forecast System precipitation forecasts especially over the Central California and other regions impacted by landfalling atmospheric rivers," said Tallapragada.

"Data collected by NOAA’s G-IV and the U.S. Air Force’s WC-130’s during an unprecedented series of atmospheric rivers in January 2023 contributed to more than 10% improvement in National Weather Service Global Forecast System precipitation forecasts especially over the Central California and other regions impacted by landfalling atmospheric rivers,"

Rivers in the sky

Atmospheric rivers form when winds over the Pacific send a ribbon of warm, moisture-laden air toward the West Coast. These rivers in the sky flow at altitudes mostly below 10,000 feet altitude and can measure 500 miles across and 2,000 miles long. When an atmospheric river hits mountains, such as California’s Sierra Nevada, it is forced even higher in the atmosphere where cooler temperatures condense its vapor, rapidly transforming it into huge amounts of rain or snow concentrated over one to three days.

The average atmospheric river carries an amount of water vapor roughly equivalent to 25 times the average flow at the mouth of the Mississippi River, but severe atmospheric rivers can transport even more. The intense rain and snow storms caused by atmospheric rivers can account for up to half of California’s annual rainfall.

Atmospheric rivers are expected to become stronger as human-caused climate change heats up the globe, because hotter air can hold more moisture, said Ralph. Climate models also suggest that dry spells between these intense bouts of precipitation are likely to become more pronounced, ping-ponging California between bouts of extreme weather and creating what some call “weather whiplash.”

Planes, buoys, and balloons

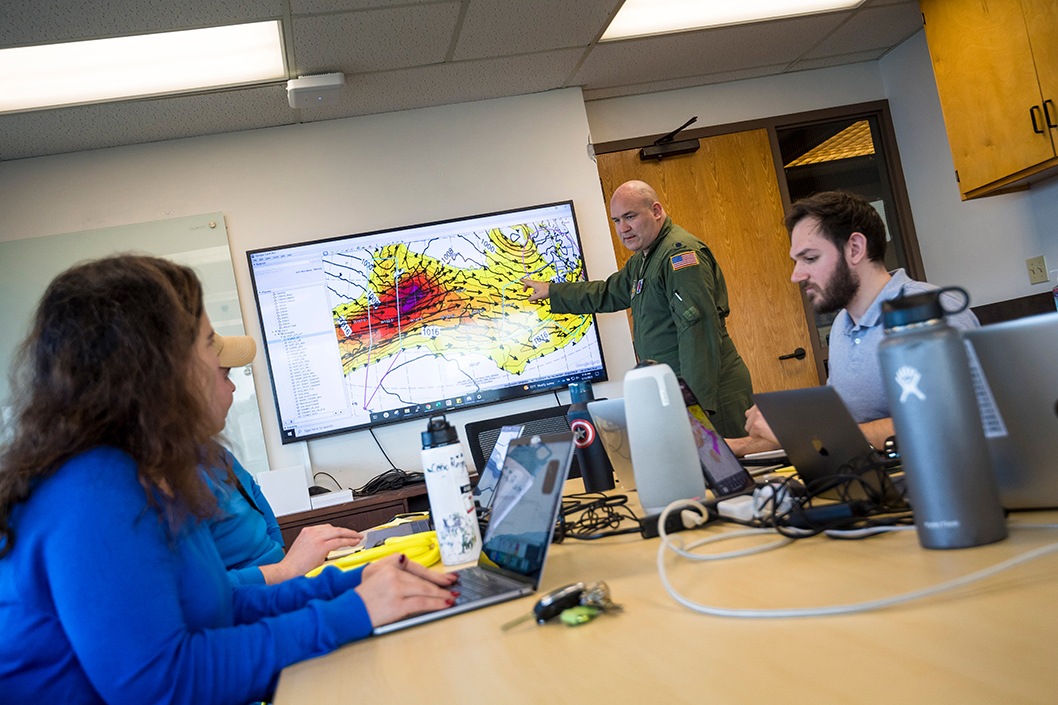

The aim of AR Recon is to “fill in information gaps with direct observations of atmospheric rivers and improve forecasting to inform Western decision-makers regarding storm impacts, water management, and flood mitigation,” said Anna Wilson, Field Research Manager at Scripps’ CW3E and AR Recon coordinator. Advanced warning can help reservoir operators to manage water levels or help state and local officials issue warnings to areas at risk of flooding, she added.

The AR Recon program has expanded since its first flights in 2016 as its data has been shown to improve forecasting. Last year, AR Recon data improved three-day lead time forecasts of heavy precipitation over California by up to 12% – a level of improvement which roughly equates to 8 additional years of honing forecast models with traditional methods.

The core elements of the AR Recon program are the U.S. Air Force Reserve’s WC-130J Super Hercules aircraft and NOAA’s Gulfstream IV. Each of these aircraft are outfitted to fly into and above intense weather to collect huge amounts of meteorological data.

The primary way the aircraft collect these data is by dropping about thirty cylindrical instruments called dropsondes into the atmospheric river in each flight. Each dropsonde has a small parachute and as it floats down to the ocean it collects and transmits data back to the aircraft including air temperature, pressure, water vapor, and wind speed. The dropsondes are “a bit like an MRI for an atmospheric river, they let us see the internal structure,” said Ralph.

Each flight is meticulously coordinated between scientists, forecasters, and flight navigators to pinpoint where to deploy dropsondes into the atmospheric river to collect the most useful data. In the 2022-2023 season, AR Recon’s 51 flights successfully deployed 1,380 dropsondes in the North Pacific.

This season the flight windows for both the U.S. Air Force Reserve WC-130J and the NOAA Gulfstream IV aircraft are longer than ever.

The U.S. Air Force Reserve WC-130J aircraft are available as resources permit for the months of November, December, and March. Four aircraft will be fully assigned to AR Recon beginning January 3, 2024. Two will be stationed in California until February 28 and, for the first time, the other two will be stationed in Guam until January 13.

Ralph said having aircraft in Guam this season will be a huge advance for AR Recon. “Atmospheric rivers usually move from west to east in the Pacific,” said Ralph. “The farther west we can go in collecting observations the greater potential we have for improving the lead time in our forecasts.”

NOAA’s G-IV will be stationed in Hawaii and is set to be fully assigned to AR Recon from December 1-22 and January 3-February 20 for a total window of 71 days, a significant increase from last season’s 49 days. In coming years, NOAA is also updating their aircraft from the G-IV to the G550, which is capable of flying longer duration missions. The first of two new G550 aircraft is expected to be operational for the 2025-2026 AR Recon missions.

AR Recon is also experimenting with a promising method known as airborne radio occultation, (ARO) which was invented by Scripps geophysicist and atmospheric scientist Jennifer Haase. The technology measures delays in the signals from GPS satellites to infer atmospheric properties such as moisture and temperature up to 186 miles (300 km) to the sides of the aircraft, adding additional context for the detailed observations of the dropsondes that measure directly below the aircraft. This winter, all AR Recon aircraft will be outfitted with ARO for the first time. ARO’s development was partly supported by a Navy initiative that invests in the development of research instrumentation.

In addition to these flights, AR Recon also adds atmospheric pressure sensors to ocean buoys that collect water temperature and wave measurements as part of the NOAA-funded Global Drifter Program at Scripps. These buoy deployments, which target areas of the Pacific where atmospheric rivers form and have been shown to improve forecast model accuracy, are a collaboration between CW3E and the Lagrangian Drifter Laboratory at Scripps led by research oceanographer Luca Centurioni. The 2023-2024 season will see the deployment of 83 drifter buoys via ships and aircraft, a marked expansion from last season’s tally of 50.

Finally, during atmospheric river events, AR Recon’s land-based stations release weather balloons called radiosondes, which are similar to the dropsondes released from the aircraft, but ascend upwards measuring pressure, temperature, and relative humidity. These radiosondes can ascend up to 115,000 feet and drift more than 125 miles. This season, AR Recon is adding two new stations to deploy weather balloons in Aberdeen and Tacoma in Washington State, adding to existing California launch sites in La Jolla, Catalina Island, Seven Oaks Dam, Bodega Bay, and Marysville.

More data, better forecasts

Many of these observations will be assimilated in real-time into weather forecast models to deliver more precise forecasts to flood control managers, water supply authorities, and reservoir operators so they can prepare for and mitigate flooding or take advantage of the water supplied by atmospheric rivers.

To this end, the AR Recon program works closely with Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations (FIRO), a multi-agency effort to efficiently manage water levels in California reservoirs. CW3E pilot studies showed that AR Recon-improved forecasts of atmospheric rivers increased water reliability at Lake Mendocino in Northern California, with the Sonoma Water Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and at the Prado Dam in Southern California. AR Recon’s forecasts enhanced water reliability by improving streamflow forecasts generated by the NWS Hydrologic Ensemble Forecast System that FIRO uses to inform water management.

NOAA and CW3E are also developing a new high-resolution Atmospheric River Modeling and Data Assimilation System within the Unified Forecast System framework for improved prediction of atmospheric rivers and their impacts on the U.S. West Coast. Among other improvements, the new modeling system is being designed to make better use of AR Recon data.

“The AR Recon program fills a big information gap over the Pacific Ocean where these atmospheric rivers form,” said Ralph. “Climate models suggest atmospheric rivers are only going to become more important as hazards and as water sources, making efforts like ours to better forecast and understand them an essential facet of adapting to our world’s changing climate.”

Follow the work of Scripps scientists at the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes on X (formerly Twitter) at @CW3E_Scripps, the U.S. Air Force Reserve 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at @53rdWRS, and NOAA Aircraft Operations Center at @NOAA_HurrHunter.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.