Antarctic Bottom Waters Freshening at Unexpected Rate

Shift could disturb ocean circulation and hasten sea level rise, researchers say

By:

- Robert Monroe

Media Contact:

- Robert Monroe - scrippsnews@ucsd.edu

- Mario Aguilera - maguilera@ucsd.edu

Published Date

By:

- Robert Monroe

Share This:

Article Content

Aboard Scripps Oceanography research vessel Roger Revelle, WHOI and Scrippps researchers gathered seawater samples using an instrument called a rosette—a rose-like array of 36 bottles that can be individually opened and closed to collect samples at different locations and depths in the ocean. Photo: Alison Macdonald, WHOI

In the cold depths along the seafloor, Antarctic Bottom Waters are part of a global circulatory system, supplying waters rich in oxygen, carbon, and nutrients to the world’s oceans. Over the last decade, scientists have been monitoring changes in these waters.

But a new study from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego suggests these changes are themselves shifting in unexpected ways with potentially significant consequences for the ocean and climate.

In a paper published Jan. 25 in the journal Science Advances, a team led by WHOI oceanographers Viviane Menezes and Alison Macdonald and Scripps researcher Courtney Schatzman report that Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) has freshened (become less saline) at a surprising rate between 2007 and 2016—a shift that could alter ocean circulation and ultimately contribute to rising sea levels.

“If you change the circulation, you change everything in the ocean,” said Menezes, a WHOI postdoctoral investigator and the study’s lead author. Ocean circulation drives the movement of warm and cold waters around the world, so it is essential to storing and regulating heat and plays a key role in Earth’s temperature and climate. “But we don’t have the whole story yet. We have some new pieces, but we don’t have the entire puzzle.”

The puzzle itself isn’t new; past studies suggest that AABW has been undergoing significant changes for decades. Since the 1990s, an international program of repeat surveys has periodically sampled certain ocean basins around the world to track the circulation and conditions at these spots over time. Along one string of sites, or “stations,” that stretches from Antarctica to the southern Indian Ocean, researchers have tracked the conditions of AABW—a layer of profoundly cold water less than 0°C (it stays liquid because of its salt content, or salinity) that moves through the abyssal ocean, mixing with warmer waters as it circulates around the Antarctic continent in the Southern Ocean and northward into all three of the major ocean basins.

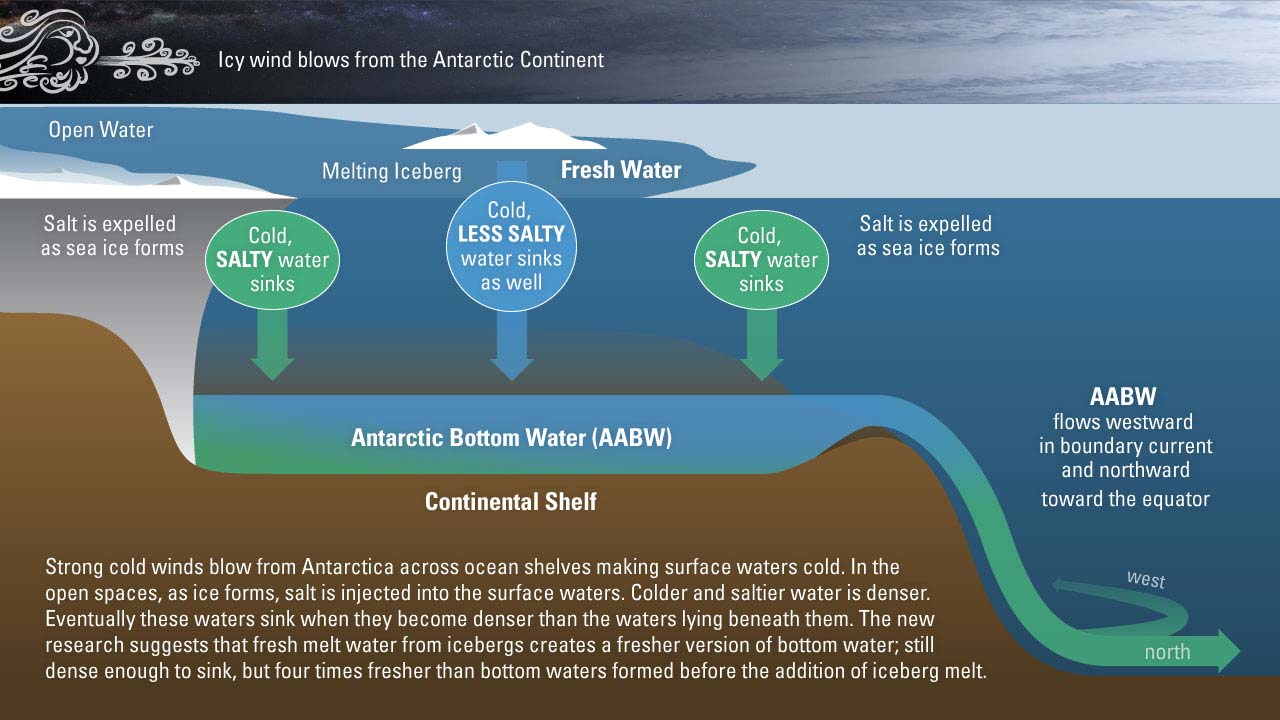

The AABW forms along the Antarctic ice shelves, where strong winds cool open areas of water, called polynyas, until some of the water freezes. The salt in the water doesn’t freeze, however, so the unfrozen seawater around the ice becomes saltier. The salt makes the water denser, causing it to sink to the ocean bottom.

“These waters are thought to be the underpinning of the large-scale global ocean circulation,” said Macdonald, a WHOI senior research specialist and the study’s co-author. “Antarctic Bottom Water gets its characteristics from the atmosphere—for example, dissolved carbon and oxygen—and sends them deep into the ocean. Then, as the water moves around the globe, it mixes with the water around it and they start to share each other’s properties. It’s like taking a deep breath and letting it go really slowly, over decades or even centuries.”

As a result, the frigid flow plays a critical role in regulating circulation, temperature, and availability of oxygen and nutrients throughout the world’s oceans, and serves as both a barometer for climate change and a factor that can contribute to that change.

Infographic on Antarctic Bottom Water freshening. Image: Eric Taylor, Woods Hole Oceanographic.

A past study using the repeat survey data found that AABW had warmed and freshened between 1994 and 2007. When Macdonald, Menezes, and Schatzman revisited the line of stations, they measured how AABW has changed in the years since.

During the austral summer of 2016, they joined the crew of Scripps Research Vessel Roger Revelle and cruised north from Antarctica to Australia, braving frequent storms to collect samples every 30 nautical miles. In a shipboard lab, they analyzed the samples using data from conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensors, which measure the water’s salinity, temperature and other properties. Schatzman processed the raw data.

"It is exciting to be closely involved with this research,” said Schatzman. “We have seen similar results aboard the U.S. Antarctic Program research ship Nathaniel B. Palmer in 2011. TAMU scientists Alexander Orsi and Scripps scientist James Swift identified Antarctic Bottom Water freshening in the western Ross Sea as well. New findings like this help make the long hours even more worthwhile."

The team found that the previously detected warming trend has continued, though at a somewhat slower pace. The biggest surprise, however, was its lack of saltiness: AABW in the region off East Antarctica’s Adélie Land has grown fresher four times faster in the past decade than it did between 1994 and 2007.

“I thought, ‘Oh wow!’ when I saw the change in salinity,” said Menezes. “You collect the data and sometimes you spend 2 to 3 years to find something, but this time we knew what we had within hours, and we knew it was very unexpected.”

Such a shift, were it global, could significantly disrupt ocean circulation and sea levels.

“The fresher and warmer the water is, the less dense it will be, and the more it will expand and take up more space – and that leads to rising sea levels,” Macdonald said. “If these waters no longer sink, it could have far reaching affects for global ocean circulation patterns.”

Questions remain around the cause of the shift. Menezes and Macdonald hypothesize that the freshening could be due to a recent landscape-changing event. In 2010, an iceberg about the size of Rhode Island collided with Antarctica’s Mertz Glacier Tongue, carving out a more-than-1,000-square-mile piece and reshaping the icescape of the George V/Adélie Land Coast, where the AABW observed in this study is thought to form. The subsequent melting dramatically freshened the waters there, which may have in turn freshened the AABW as well. Future studies could use chemical analysis to trace the waters back to the site of the collision and calving and confirm the hypothesis.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.