By:

- Brittany Hook

Published Date

By:

- Brittany Hook

Share This:

Usurp the Burp

How seaweed could help curb cow burps—one of California’s greatest sources of methane emissions

Marine ecologist Jennifer Smith has been cultivating Asparagopsis taxiformis seaweed in her lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Researchers have found that adding small amounts of this seaweed to cattle feed can dramatically reduce methane-laden cow burps. Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

Agricultural and marine scientists at the University of California have joined forces to combat one of the greatest sources of methane emissions in California: cow burps.

Scientists have found that a certain species of red algae seaweed, Asparagopsis taxiformis, produces a compound that could halt bovine production of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that is 30 times more potent than CO2. This is significant because more than half of all methane emissions in California come from livestock, primarily from the state’s 1.8 million dairy cows as they burp, exhale, fart and produce manure. Of these cattle-related emissions, belches pack the most punch, accounting for roughly 95% of the methane released into the environment.

When Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego marine ecologist Jennifer Smith read about a recent UC Davis study involving Asparagopsis, she was intrigued. With a background in marine botany, specifically phycology—the study of seaweeds and algae—Smith is very familiar with Asparagopsis. In fact, she recalled seeing some of the red algae growing haphazardly in a tank at Scripps’ Experimental Aquarium, a research facility supplied by seawater pumped in from the end of Scripps Pier.

Asparagopsis taxiformis seaweed in the wild just off Catalina Island in California. Photo by Jennifer Smith

Ongoing research led by agricultural scientists at UC Davis has found that adding just a small amount of Asparagopsis seaweed to cattle feed can dramatically reduce methane emissions from dairy cows by more than 50 percent. These preliminary results are promising, but still very little is known about whether it’s possible to grow enough seaweed to meet the potential demands of the livestock industry.

Seeking an opportunity for collaboration, in fall of 2018, Smith reached out to Ermias Kebreab, an animal science professor at UC Davis and leader of the seaweed study. Smith was interested in trying to grow Asparagopsis in the lab—something which has never been done before—and exploring cultivation of this red algae on a larger scale. Kebreab replied almost immediately, and soon Smith found herself embarking on a seaweed passion project loaded with potential.

“I'm really excited about all of the research opportunities that lie ahead to essentially understand the complexities of this beautiful red seaweed and to try to understand how we might be able to use it to mitigate methane production in cattle,” said Smith, associate professor at the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at Scripps.

Smith is well known for her research on coral reefs, particularly her work with the 100 Island Challenge project that aims to map and collect coral reef data from islands around the globe. But she also has experience with seaweed cultivation through her work with California Seaweed Company, a startup she co-leads with former student Brant Chlebowski that seeks to sustainably cultivate top quality culinary seaweeds.

She is well aware of the challenges that she will face with her latest venture.

“Asparagopsis is a complicated seaweed and little is known about its biology, so that poses a lot of opportunity from a scientific perspective, and it's not something that we can just start scaling tomorrow,” said Smith. “We have a lot of work to do to learn more about its biology, physiology and ecology before we can develop a model for scaling cultivation.”

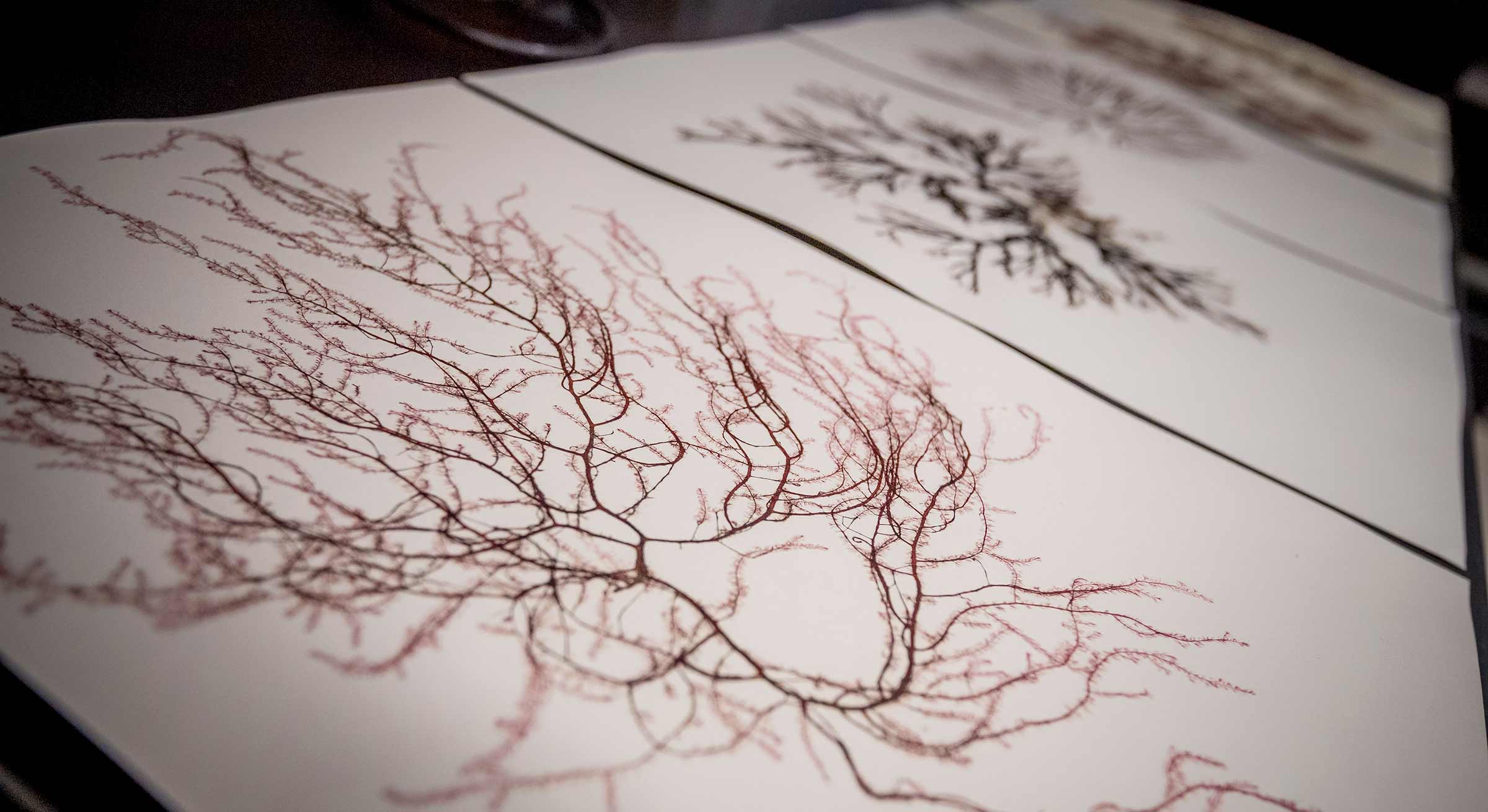

Pressed seaweed specimens serve as important historical and taxonomic records for marine scientists. These recently pressed seaweed samples are stored in the herbarium, a dried plant archive, housed in the Smith Lab.

The UC Davis study was prompted, in part, by the passing of a recent California law requiring dairy farmers and other producers to cut methane emissions 40 percent by 2030. As businesses and farmers are looking for affordable and effective methods to curb methane emissions, there has been increased interest in a potential seaweed solution.

“We asked Jen to join us because we needed a marine biologist to work on how best to grow the seaweed and scale up production,” said Kebreab, Sesnon Endowed Chair in the Department of Animal Science at UC Davis. “Once we show its potential, we expect high demand so we need to start working on meeting that demand—and Jen would be crucial to the success of this technology.”

Shortly after her initial conversation with Kebreab, Smith went back to the Experimental Aquarium in search of the “pink scuzzy” seaweed she had seen there two years prior. To her delight, it was still in the aquarium, growing strong. For the past few months, she’s been using these initial samples to grow the seaweed, similar to the way succulents can be propagated from a single clipping.

These samples of Asparagopsis taxiformis seaweed are in the sporophyte phase of growth; just one of the three phases that exist in this alga’s life cycle.

The Asparagopsis samples now housed in the Smith Lab are presented in a dazzling array of bubbling flasks filled with what looks like tiny pink pom poms moving wildly about. These little pink balls are actually algae in the sporophyte phase of growth; just one of the three phases that exist in this alga’s life cycle. Smith is particularly interested in working on the seaweed in this smaller phase because she’s seen some of the samples double in size in less than a week.

Right now, she’s trying to find the “sweet spot” where the seaweed is growing at its highest rate, while also increasing its concentration of bromoform—the compound responsible for interfering with the enzymes that make methane in a cow’s gut.

Smith has also been conducting a variety of experiments to understand how the chemical composition and growth rates of the seaweed change under different laboratory conditions including temperature and light, nutrient concentration, and CO2 concentration.

In order to ensure clean cultures, she is not using flow through seawater, as this has the potential to bring in “hitchhikers,” potentially harmful marine critters or contaminants that could foul the samples.

Smith notes that no one has ever completed the lifecycle of Asparagopsis in captivity, and there’s much work to be done to see if cultivation of this red algae is possible on a larger scale.

Asparagopsis taxiformis is a subtropical species native to places including Australia and the Hawaiian Islands, but it’s also found in areas further north including Baja California, Mexico and various locations off Southern California including San Diego and Catalina Island.

The dried seaweed used for the UC Davis study was harvested in the wild from Australia, where it’s most abundant. It’s possible that in the future, researchers at UC Davis might use seaweed samples grown by Smith in her studies, but she does note that there’s a limit to what one lab can produce.

Agricultural scientists at UC Davis have found that adding just a small amount of Asparagopsis seaweed to cattle feed can reduce methane emissions from dairy cows by more than 50 percent. Image by Olha Rohulya/IStock

“I don’t think that I will personally be growing all the seaweed that's going to feed all the cows, but I would certainly like to contribute to the technology development, the approaches and finding the most efficient and sustainable way of doing it,” said Smith.

In the near future, Smith plans to collect different populations of Asparagopsis from other places off California so she can have different genetic strains growing in the lab. She’s also involved in another collaborative seaweed study in which scientists will sequence the genome of 12 different types of seaweed, one of them being Asparagopsis.

Her long-term goal is to understand the most efficient and carbon negative way to move from cultivating seaweed in the laboratory to cultivating it outside in large tanks, or potentially even in the open ocean, a venture she thinks is much farther down the road. But for now, Smith says working on land-based cultivation is the way to go.

Smith’s current work on Asparagopsis cultivation is a one-woman show, but she plans to expand her research team soon. She is driven by the possibility of contributing to research that could have lasting impacts on the environment. Unlike CO2, which lingers in the atmosphere for hundreds to thousands of years, methane has a relatively short lifespan of about 10 years, meaning changes made today could have an impact in the near future.

“The opportunity to potentially manage methane emissions from cow burps had never really been on the table,” said Smith. “But with this unusual collaboration—a marine biologist working with the livestock industry and livestock scientists—we might have an influence on greenhouse gas emissions. It's a crazy marriage of three totally disparate fields of science and I’m just really excited to be part of that.”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.