Underwater Soundscapes

Scientists use high tech equipment to study marine life and inform protection efforts.

Published Date

Story by:

Share This:

Article Content

This story was published in the Spring 2023 issue of UC San Diego Magazine.

Far from crashing waves and boisterous beachgoers at the shoreline, one might expect the deep sea to be a quiet refuge. But even in the dark depths of the ocean, a cacophony of human-related noise can be detected, often the result of activities related to shipping activity, military sonar and energy exploration.

“We perceive the world with our eyes, but the animals in the ocean rely on sound,” says Simone Baumann-Pickering, a professor and biological oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “And so changes in the soundscape are going to be so much more impactful for them than for us.”

Baumann-Pickering began her academic career with a bachelor's degree in media engineering and later studied echolocation in bats in her home country of Germany.

“I knew about sound from the engineering side of things, and bats are cool,” she says with a shrug and a smile before explaining that a growing affinity for marine science prompted her to change course. “From bats to dolphins is not that far of a stretch.”

Baumann-Pickering now leads the Scripps Acoustic Ecology Laboratory, a group of researchers working to contribute to the management and conservation of marine mammals in their ecosystem. She and her team work in collaboration with other campus labs, including the Scripps Whale Acoustics Laboratory and the Scripps Machine Listening Lab, to uncover the mysteries of the marine environment using a network of underwater listening devices and other technology.

“We're taking advantage of sound as a sensing method, in a way no other method allows us to do,” she says. “These devices give us the opportunity to go year-round, in remote places and at night.”

This spring, she and her team will lead a seagoing expedition to service and collect data, a task completed every six months. They record all the sounds, from low-frequency ship or baleen whale sounds to very high-frequency echolocation clicks of dolphins. The data is reviewed and studied at a processing facility at Scripps Oceanography.

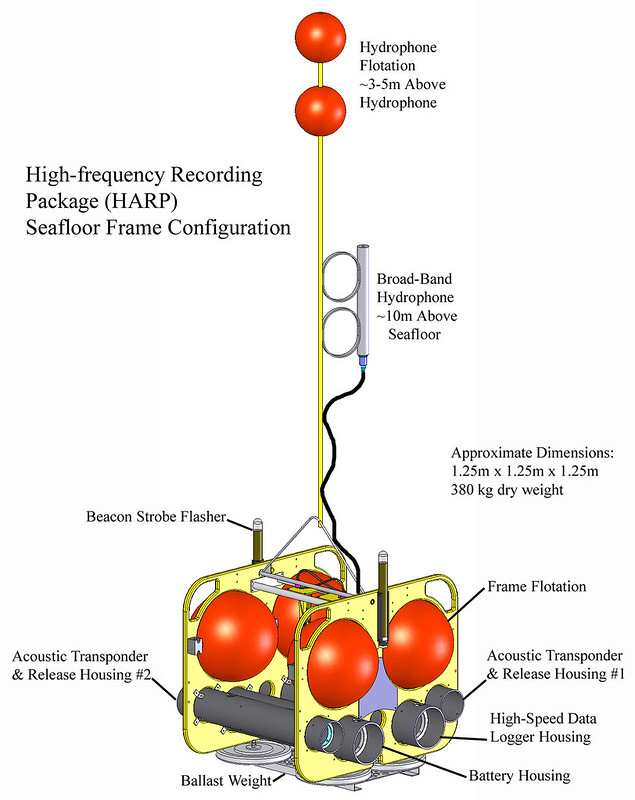

One of the instruments, the Scripps-developed High-frequency Acoustic Recording Package (HARP), sits on the seafloor with a hydrophone, or underwater microphone, to record the sounds of predators such as marine mammals.

“You would think that whales and dolphins are big enough that we know a lot about them, but the time series measurement of top predators is really difficult,” she says. “The acoustic time series that we are generating now helps fill gaps to understand overall trends in population.”

For several years, Baumann-Pickering has led a project funded by the Office of Naval Research to study the noise impact of naval activities on whales, dolphins and porpoises in waters off Southern California.

“We are studying how these whales naturally behave and what happens when we introduce anthropogenic noise,” says Baumann-Pickering.

The resulting data will help the U.S. Navy understand the impacts of its national security-related activities — for example, the training exercises that take place off the coast of San Diego and the related use of mid-frequency active sonar — and inform mitigation efforts.

“The ultimate goal is to understand the kind of disturbance levels we have and figure out if it’s going to be notable for a population within a certain region over the long term,” she says.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.