UC San Diego-led Team Discovers Scarab from Time of Biblical Pharaoh

Published Date

Article Content

Dig site at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan

Archaeologists led by University of California, San Diego Anthropology Professor Thomas E. Levy have discovered a small Egyptian scarab bearing the name of Sheshonq I – the only historical figure mentioned in both the Hebrew Bible (as Shishak) and Egyptian monuments indirectly related to the Biblical King Solomon.

A description of the discovery was published last week in the British journal Antiquity. Levy, Stefan Münger of Bern University and Jordanian archaeologist Mohammad Najjar are co-authors on the paper.

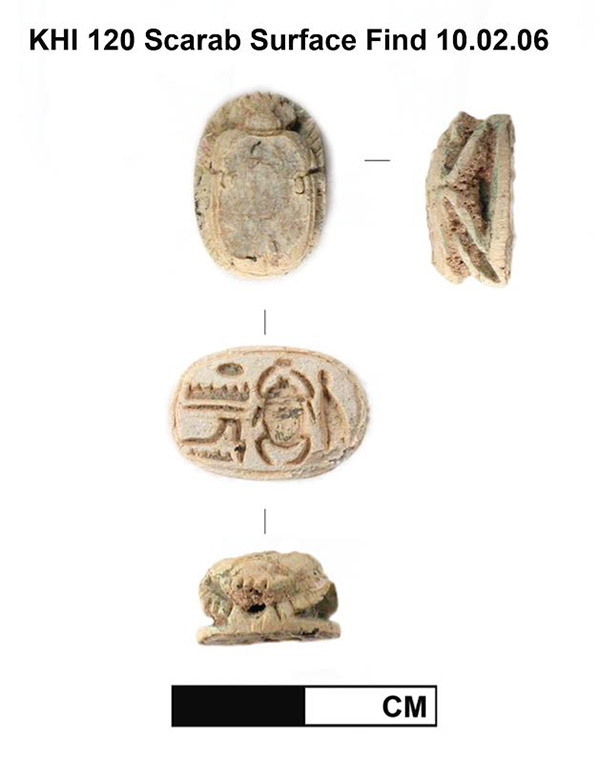

The scarab was found at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan in southern Jordan at the site of an ancient copper manufactory dating to the Early Bronze Age, c. 3000-2000 BC, which also bears evidence of Iron Age (ca. 1000 – 900 BC) smelting activities. Most scholars agree that Sheshonq I, the founder of the 22nd Egyptian Dynasty, may be identified with the Pharaoh Shishaq mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament; I Kings 11:40, 14:25, and 2 Chronicles 12:2-9). Essential evidence for Sheshonq’s reign comes from a monumental carving on the Bubastite Portal of the Amun-Re temple complex at Karnak in Egypt, which lists the cities that Sheshonq I conquered.

Detail of the scarab found at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan, which bears the name of the Egyptian Pharoah Sheshonq I.

The discovery marks the second time in the archaeological history of the southern Levant (Israel/Palestine/Jordan) that an epigraphic text has been found bearing the name of Sheshonq, whose rule is traditionally dated to 945 – 924 BCE (known to archaeologists as the Iron Age IIA period). University of Chicago excavators discovered the first such artifact – a large fragment of a victory stele or monument that the Egyptians erected to celebrate Sheshonq I’s military campaign – in the 1930s at the famous site of Megiddo in Israel.

“While the word ‘Pharaoh’ appears 240 times in the Bible, only in a handful of instances are a specific name given,” Levy added. “The Shishaq narrative is thus the earliest event described in the Hebrew Bible that is supported by an extra-biblical text.”

Levy, who is the associate director for the Qualcomm Institute's Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology (CISA), noted that amulets in the shape of scarab beetles became very popular in ancient Egypt beginning around 2000 BCE and remained popular throughout the rest of pharaonic times.

“Their function, and thus their symbolism, changed often,” he added. “Most of the time, they were amulets, sometimes jewelry and periodically they were inscribed for use as personal or administrative seals. We think this is the case with the Sheshonq I scarab we found.”

Although the scarab was found in 2006 as part of a ‘deep time’ study of the role of ancient mining and metallurgy in this region of the Faynan district, it is being published by the UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press this coming November. The major two-volume monograph concerning Levy’s expeditions in southern Jordan will include a chapter on the Egyptian amulets found in their excavations and surveys – including a detailed treatment of the Sheshonq I scarab.

The scarab was discovered after Levy invited UC San Diego student Ben Volta to join his dig, per the recommendation of Volta's adviser, Geoff Braswell of the UC San Diego Department of Anthropology. Braswell, who specializes in Mesoamerican archaeology, wanted Volta to gain archaeological experience in Old World, Middle Eastern archaeology.

“The first day of the expedition," recalled Levy, "I was leading a hiking tour for the undergraduate and graduate students around Faynan. We walked several kilometers to the Early Bronze Age copper manufactory at Khirbat Hamra Ifdan. In several areas of the site, there are concentrations of typical large Iron Age smelting slags. After my nattering on to the students for some time, Ben came up and showed me a little scarab in his hand. ‘What is this thing?’ he asked. Like all good field archaeologists, Ben had his eyes peeled to the ground and found the scarab on the surface.”

Although the scarab was not found in situ– which might have led to further archaeological discoveries – Eric H. Cline, Professor of Classics and Anthropology at George Washington University and Co-Director of the Megiddo Excavation, called the discovery of the scarab “extremely exciting and potentially very significant.”

“Its rapid publication by Levy, Münger, and Najjar will now allow other scholars to take this artifact into consideration in their studies, alongside the stela fragment found in the 1920s at Megiddo,” added Cline. “It seems quite possible that additional objects of this pharaoh will be found in the future, which may shed additional light on his campaign to this region."

University of Toronto Professor Timothy Harrison – who published some of the University of Chicago's early excavated assemblages of the Iron Age Megiddo material – agrees that the scarab "provides important new epigraphic evidence of the extent of Sheshonq I's military and political activities in the southern Levant at the end of the United Monarchy Period in the Hebrew Bible."

"The scarab, found in the Wadi Faynan south of the Dead Sea, supports previous suggestions that Sheshonq campaigned in this mineral rich and strategic region," he continued, "while providing corroborating epigraphic evidence for the Egyptian and Biblical accounts of this campaign, which occurred during the reign of Rehoboam, Solomon’s son and successor as king of Israel.”

According to the Biblical narrative, five years after the death of King Solomon, Shishaq (Sheshonq I) invaded the land conquering numerous cities in the Jezreel Valley, the international road in the Sharon Plain, Penuel and Mahaniam in Transjordan, and sites in the northern Negev and Negev highlands in the south.

Levy noted that it’s possible to read a list of place names inscribed at Karnak and recreate the route of Sheshonq’s campaign in Canaan, but his team’s discovery “adds an important new datum point for identifying the route of what the noted Egyptologist Professor Kenneth Kitchen (University of Liverpool) refers to as a ‘flying wing’ of Sheshonq’s army that crossed the Negev desert.”

Levy said the find shows that Sheshonq I’s forces or representatives were in the copper ore resource zone of Jordan’s Faynan district. In 2008, he and his colleagues published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science that identified a major disruption in industrial copper production in Faynan, which they attributed to the Sheshonq campaign. They based their conclusion on a series of excavations of rock layers in the area of an ancient copper slag mound at Khirbat en-Nahas dated with numerous high precision radiocarbon dates. They were able to link to the site a series of 22nd Dynasty amulets that were common at the time of Sheshonq I.

“However,” said Levy, “the scarab we found that bears Sheshonq I’s name is the first time we can definitively link the disruption to his forces.”

The scarab is now in the main storage facility of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.