This Wireless, Handheld, Non-invasive Device Detects Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Biomarkers

Next steps include testing saliva and urine samples with the biosensor

Story by:

Published Date

Article Content

An international team of researchers has developed a handheld, non-invasive device that can detect biomarkers for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. The biosensor can also transmit the results wirelessly to a laptop or smartphone.

The team tested the device on in vitro samples from patients. The tests showed the device is as accurate as the state of the art testing methods. Ultimately, researchers plan to test saliva and urine samples with the biosensor. The device could be modified to detect biomarkers for other conditions as well.

Researchers present their findings in the Nov. 13, 2023 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

The device relies on electrical rather than chemical detection, which researchers say is easier to implement and more accurate.

“This portable diagnostic system would allow testing at-home and at point of care, like clinics and nursing homes, for neurodegenerative diseases globally,” said Ratnesh Lal, a bioengineering, mechanical engineering and materials science professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and one of the paper’s corresponding authors.

By the year 2060, about 14 million Americans will suffer from Alzheimer’s Disease. Other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s, are also on the rise. Current state of the art testing methods for Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s require a spinal tap and imaging tests, including an MRI. As a result, early detection of the disease is difficult, as patients balk at the invasive procedures. Testing is also difficult for patients who are already exhibiting symptoms and have difficulty moving as well as those who have no early access to local hospitals or medical facilities.

One of the prevailing hypotheses in the field, which Lal has focused on, is that Alzheimer’s Disease is caused by soluble amyloid peptides that come together in larger molecules, which in turn form ion channels in the brain.

Lal wanted to develop a test that would be able to detect amyloid beta and tau peptides – biomarkers for Alzheimer’s – and alpha synuclein proteins – biomarker for Parkinson’s – non invasively, specifically from saliva and urine. He wanted to rely on electrical rather than chemical detection, as he believes it is easier to implement and more accurate. He also wanted to build a device that could wirelessly transmit the test results to the patient’s family and physicians. The device is the result of his three decades of expertise, as well as his collaboration with researchers globally, including those co-authors in this work from Texas and China.

“I am trying to improve quality of life and save lives,” he said.

To realize Lal’s vision, he and colleagues adapted a device they developed during the COVID pandemic to detect the spike and nucleoprotein proteins in the live SARS-CoV-2 virus, which they described in PNAS in 2022. That breakthrough had been made possible by chip miniaturization and by large-scale automation of biosensor manufacturing.

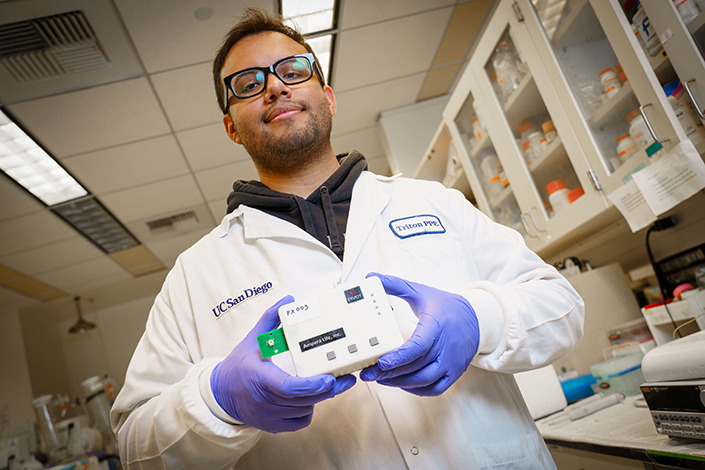

Bioengineering senior Armando Ramil holds the biosensor.

Photos: David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

How the device is made and how it works

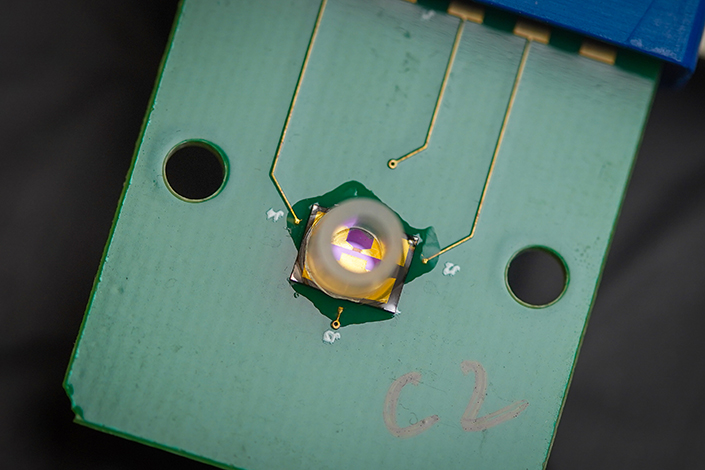

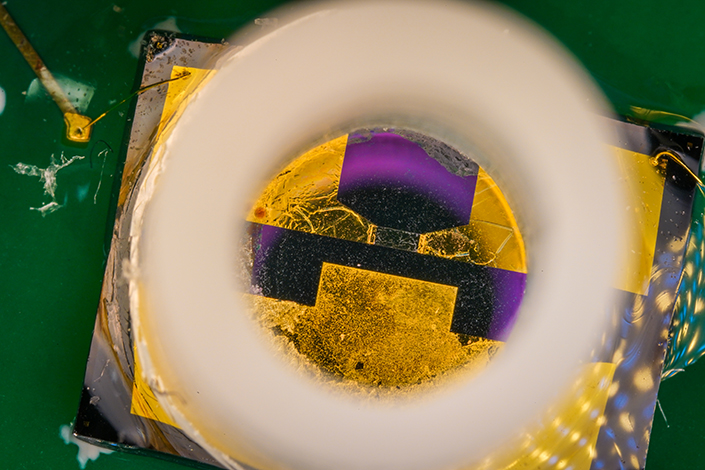

The device described in the 2023 PNAS study, consists of a chip with a high sensitivity transistor, commonly known as a field effect transistor (FET). In this case, each transistor is made of a graphene layer that is a single atom thick (GFET, with the G standing for graphene) and three electrodes–source and drain electrodes, connected to the positive and negative poles of a battery, to flow electric current, and a gate electrode to control the amount of current flow.

Connected to the gate electrode is a single DNA strand, which serves as a probe that specifically binds to either amyloid beta, tau or synuclein proteins. The binding of these amyloids with their specific DNA strand probe, called an aptamer, changes the amount of current flow between the source and drain electrode. The change in this current or voltage is the signal used to detect the specific biomarkers, like amyloids or COVID 19 proteins.

The research team tested the device with brain-derived amyloid proteins from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s deceased patients. The experiments showed that the biosensors were able to detect the specific biomarkers for both conditions with great accuracy, on par with existing state of the art methods. The device also works at extremely low concentrations, meaning that it needs small quantities for samples–down to just a few microliters.

In addition, the tests showed that the device performed well even when the samples analyzed contained other proteins. Tau proteins were more difficult to detect. But because the device looks at three different biomarkers, it can combine results from all three to arrive at a reliable overall result.

The technology has been licensed from UC San Diego to a biotechnology startup Ampera Life. Lal is the company’s chairman but does not receive financial support for his research from the company.

Next steps include testing blood plasma and cerebro-spinal fluid with the device, then finally saliva and urine samples. The tests would take place in hospital settings and nursing homes. If those tests go well, Ampera Life plans to apply for FDA approval for the device, hopefully in the next five or six months. The ultimate goal is to have the device on the market in a year.

Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health, the University of California San Diego and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In addition, researchers used facilities that are a part of the NSF-funded UC San Diego Materials Research Science and Engineering Center.

In pursuit of degenerative brain disease diagnosis: dementia biomarkers detected by DNA aptamer-attached portable graphene biosensor

University of California San Diego: Tyler A. Bodily, Anirudh Ramanathan, Abhijith Karkisaval, Armando Rami, Prachi Heda. M. Leite, Ratnesh Lal

Shanghai Institute of Microsystem Information Technology Shahong Wei, Yi WAng, Tie Li, Jianlong Zhao

University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Shahong Wei

University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas Nemil Bhatt, Cynthia Jerez, Md Anzarul Haque

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Sanjeev Kumar

The biosensor consists of a chip with a highly sensitive transistor, made of a graphene layer that is a single atom thick and three electrodes–source and drain electrodes, connected to the positive and negative poles of a battery, to flow electric current, and a gate electrode to control the amount of current flow.

A close up of the silicon well in the biosensor with the graphene-based transistor at the bottom.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.