The Epic Lives of Albert Lin

Published Date

Article Content

Originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Triton Magazine.

UC San Diego engineering alumnus Albert Yu-Min Lin can be described in many ways: explorer, engineer, scientist, artist, surfer, humanist, traveler, philosopher, father. It’s a challenge to capture Lin, whether in a few words or just for a quick phone call. He seems to have an endless supply of momentum—an energy, curiosity and optimism as big as the world he is continually exploring.

When I do reach Lin, he’s wrapped a day of shooting a new series for the National Geographic channel. A few days before, he’d been traveling down Norwegian fjords and soon he’d be hanging out of a Black Hawk helicopter in Jordan. But I’m able to catch him just after a dive in the English Channel; it’s late and he’s freezing, drawing a bath in his hotel room to warm up.

“It’s been wild,” he says. “We’ve been shooting through the night because it never gets dark in Norway. At like two in the morning you realize you’re supposed to be sleeping,” he adds with a laugh. But that seems to befit Lin’s mission for the show: “We’re finding places where there are secrets hidden within extreme conditions—things that might tell you more about the human story.” (The series, Lost Cities with Albert Lin, just finished its first season.)

Lin’s own story, filled with extremes and adventure and unexpected twists, can also shed light on our human condition. Born to a mother who was a former Hong Kong movie star and an astrophysicist father who took the young Lin on sabbaticals throughout Europe and Russia, he seemed destined to be on this worldly journey. In fact, his middle name, Yu-Min, translates to “Citizen of the Universe.”

But his own age of discovery began at UC San Diego in classes with professor Marc A. Meyers, a materials scientist in the Jacobs School of Engineering. “He was a renaissance person,” Lin recalls. “I always thought you had to be an expert in one thing. But he wrote poetry and novels; he went down the Amazon. He did all these other things, but he was also a materials scientist. He was a human being.”

For Lin, Meyers sparked a classic romantic notion of the explorer-scientist, so much so that every summer Lin would take shoestring trips to cultivate his own sense of adventure.

One such trip found Lin on a train in the Gobi Desert, in the middle of the night on the Chinese- Mongolian border. A chance encounter led him to intervene on behalf of a Mongolian woman and her friend who were having trouble making the crossing. “The situation was intense,” he recalls. “It was a very scary place to show up in the middle of the night.”

Fluent in both Mandarin and English, Lin helped translate for the couple and got them safely through the border—a seemingly small yet important act that would end up changing the course of his trip, and his future. In a gesture of gratitude, the woman took Lin in, introducing him to her family as well as their nomadic culture, one that goes back thousands of years into ancient history and involves the emperor Genghis Khan. Lin became an adopted son of sorts: “They gave me a horse and taught me about a history I didn’t even know was there—one in which Khan was a hero,” he says. “Of course, he was a warrior at the time, but he changed the entire course of the planet within a single lifetime, defeating armies that were more advanced by every account.”

Lin returned home and finished his master’s and PhD in materials science and engineering, but the fascination with Khan stuck with him. Upon graduation he poured himself into the subject, selling everything he owned and sleeping in his car and on couches, devoting all his time and resources to building an exploratory project of his own. He wanted to investigate the history of Khan and go deeper than anyone into the mystery of his final resting place. He gave himself one year.

“I ate so much ramen and eggs I almost get sick thinking about it today,” he says. “But it was one of the happiest times in my life in some ways.” Such a minimalistic life allowed for intense focus on exploring the lost history of Khan from a scientific and engineering standpoint, an approach that would be shaped by a lecture he attended in graduate school by Maurizio Seracini ’73. Seracini talked about new technology that allowed researchers to study cultural artifacts without harm or intrusion, and opened Lin’s eyes to how they could see below the surface of paintings and through walls using multispectral imaging and other non-destructive techniques. The lecture also introduced him to the interdisciplinary endeavors of the Qualcomm Institute, known then as the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, or Calit2.

“I immediately fell in love with that place,” Lin remembers. He started showing up at the institute, a research unit on campus, every day. “I’d be in a suit, but with no job, just pretending I belonged there. I found a desk to sit at, and I just sort of shoehorned my way in.”

Though he was essentially a squatter, institute directors Larry Smarr and Ramesh Rao nurtured Lin’s drive and curiosity. “They didn’t dismiss me,” says Lin. “It really is a place where ideas can sprout. They gave me a fishing license in a way, because they let me use this amazing place as a home base.”

Little by little, Lin built credibility and partnerships, while still being determined and scrappy. It all paid off when the president of National Geographic made a visit to campus. Lin figured out his path, hopped on his bike and caught him in front of the Price Center. “I had a one-page proposal and a one-minute pitch,” he says with a laugh. “I wouldn’t let him leave until he gave me his card— and that’s when really I started harassing him.”

Lin earned a grant from National Geographic for his Khan project, and with the connections fortuitously made on his previous trip, he gained access to Mongolia’s so-called “Forbidden Zone,” where Khan’s tomb is believed to be. Lin points out that within some circles in Mongolian culture, Khan’s final resting place is considered sacred and meant to remain hidden and undisturbed, which is precisely why the novel use of ground-penetrative radar and non-invasive methods such as satellite and drone imagery proved so important.

Ultimately, the tomb was not found, but Lin piqued widespread interest in the methods employed in his search. He became National Geographic magazine’s Readers Choice Adventurer of the Year for 2009, and continued traveling the world using the same technology, searching for lost Mayan temples in Guatemala and finding secrets in ancient Chinese tombs. It was all documented in various National Geographic specials and series, making Lin became a familiar face for the organization, if not the epitome of modern exploration.

Yet in September 2016, Lin went on another excursion, this one local and relatively low-risk: an afternoon off-roading with a friend in a small 4×4 vehicle near Poway, Calif., not even 15 miles from UC San Diego. “My friend was driving and it rolled,” he says. “It was a split second, and I instinctively tried to stop it from tipping.”

He stuck out his right leg to do so, but to no avail—the roll cage landed on top of the limb, his bones splintering like bamboo. And just like that, in a cloud of dust, dirt and blood, his life was changed.

Within this turning point of loss and rebirth, Lin points out there’s a love story. He’d been dating a woman for just a week when the accident happened. She held his head as he lay in the dirt awaiting an ambulance, guiding him through deep meditation to help keep him calm and keep the pain, which would later become unbearable, at bay.

The entire time he was in the hospital, Lin says, his partner didn’t leave his side.

He remained in the hospital for a month, battling infections invading his bones, deciding whether to fight to keep the mangled limb or move on without it. Lin, the father of a young son and daughter, the avid runner, surfer and rock climber who once scaled Yosemite’s El Capitan, took to Instagram to recount his decision:

The choice was clear for many reasons (including a growing infection), but at its core it was a decision to move forward over holding on to what was already gone. This is true for so many situations in life, and it’s never easy.

Lin’s leg was amputated below the knee, and a new life began. Through a series of moments seemingly small and insignificant, he had to remaster things many take for granted: How to get a glass of water from one side of the room to the other. How to go the bathroom without relying on his partner. Yet none of these challenges would be as intense as what he would experience in the onslaught of phantom limb pain.

“It felt like it was on fire, ripping apart, folding over backwards,” he says. “The kind of pain I was feeling, it’s hard to describe. Never a relief. I was desperate.”

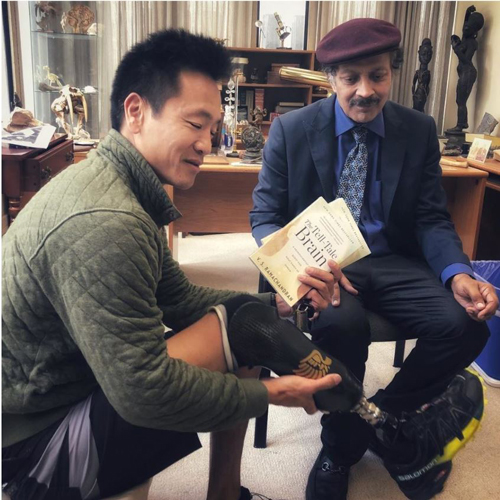

| Racked with phantom limb pain, Lin collaborated with psychology professor V.S. Ramachandran to test new applications of his novel treatment methods. |

Lin sought solutions outside of typical pain medications and traditional therapies, ones that relied on the mind. After all, the place where he was feeling pain didn’t exist anymore. A couple of weeks after becoming an amputee, he and his partner began going out to the desert, leaving his pain medications behind and relying on solitude and mental focus to try and control what he was feeling.

Lin also sought help from his colleagues at UC San Diego, in particular psychology professor V.S. Ramachandran, a leading expert in phantom limb pain. The author of the acclaimed book Phantoms in the Brain, Ramachandran is credited with developing mirror therapy, which can significantly reduce chronic pain and phantom limb pain by showing a patient a reflection of his or her painful body part.

“It’s using mirrors to trick your brain into seeing a new story,” Lin says. The two of them authored a paper published in the journal Neurocase detailing the effort it took to achieve what Lin calls “remapping the brain.” But among the most important factors in the process was being surrounded by a wide and accomplished community from UC San Diego. This included the Qualcomm Institute’s Rao, who, Lin notes, has studied the science behind cultural traditions of understanding the mind, such as mediation and yoga.

Ultimately, the key to curing this crippling pain, Lin found, “was something as simple as choosing to let my mind create a new reality.”

With this newfound knowledge and perspective he gained, Lin was ready to embrace his new life—bionic, as he likes to say. He’d seen and experienced firsthand the possibilities and potential of the human body and mind. But as so much of his success was due to his unique access to UC San Diego experts and modern medical care, it made him think about the millions of amputees without such an advantage.

“I became part of a community that was much larger than I ever knew,” he says, “but I was part of a privileged corner of that community. Ninety-five percent of the amputees in the world couldn’t do what I was doing because they didn’t have access to prosthetics.”

Just as he had used the power of technology to advance the frontiers of exploration, he set his sights on a new horizon.

One morning, last May, Lin met with about a dozen UC San Diego students working on one of the latest projects of the Center for Human Frontiers (CHF), the interdisciplinary research initiative Lin founded to harness technology to augment human potential. The students were sharing their progress with Project Lim(b)itless, a technology that could bring affordable, custom-fitting prosthetics to amputees around the world. In a conference room at the Qualcomm Institute where Lin’s center is based, they discussed the development of a cell phone app that can capture and transport photos of an amputee’s residual limb to a 3-D printer, in order to make a custom-fit prosthetic.

“It didn’t seem fair to me that I could walk down a street, or go back to surfing and scuba diving when someone nearly identical to me was begging on the streets just because of a lack of access to a simple piece of technology,” Lin says. “Prosthetics are not that complicated; it’s really just a game of trying to figure out how to customize it to your body in a way that allows it to be functional.”

The process behind Project Lim(b)itless begins with a cell phone, a few photos and a creative use of photogrammetry—the same imaging technique Lin used to map ancient sites in Mexico, China and Guatemala. In theory, an amputee could take a series of photos of their residual limb to produce a scan, then electronically deliver a virtual model of their limb to a prosthetist, who uses advanced software to design a more comfortable, custom-fitted artificial limb.

With 3-D printing added into the process, the prosthesis would take fewer hours of manpower to produce, require fewer trips to be fitted correctly, and result in significantly less cost. For amputees around the world, many of whom already have limited money and mobility, these factors could make the difference between coping and thriving.

“I want to find a way to put this into every village around the planet,” Lin says. “From the streets of Mumbai to the mountains of Nepal, I’d like to take the technology that’s already in our pockets and use it to give 40 million people their lives back.”

The project has made some significant strides forward in recent months. A new 3-D printer was installed in the Qualcomm Institute, allowing the team to create its first prototype of a socket in September. Lin, Qualcomm Institute Director Roa and a dozen students, led by mechanical and aerospace engineering PhD student Isaac Cabrera, recently traveled to India for the INK 2019 conference and to test their software with the prosthetists and amputees at Jaipur Foot, a world-renowned clinic specializing in low-cost artificial limbs.

“I recognize the privilege of my life,” Lin says, and despite being not even 40, he says he feels like he’s lived four very different lives already, given all that he has done and what he’s been through. But the loss of his leg has given him a new perspective on all of it—“all the things I’ve done in my career have been enabled because of access to a piece of technology,” he says. “Almost unknowingly, all the things I’d been doing before were in preparation for this project.”

Lin looks at the socket that just emerged from the new 3-D printer. “What we are trying to do is come up with ways to make the world a better place. And when you go for the moon, the things that come from that are remarkable.”

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.