By:

- Jackie Carr

Published Date

By:

- Jackie Carr

Share This:

The Doctrine of Doctors

The art and science of medicine evolves, but the School of Medicine's goal is constant: Create physicians who are as compassionate as they are brilliant

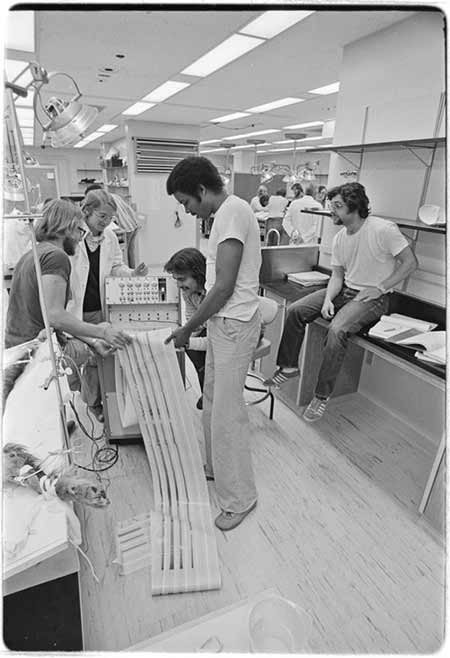

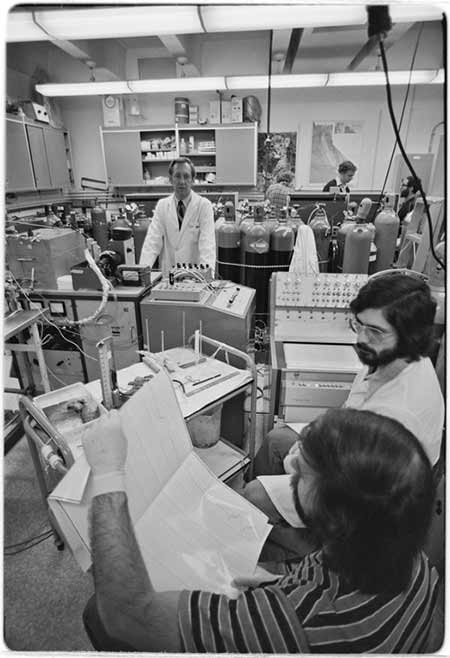

In a few months, a new class of students will begin studies at UC San Diego School of Medicine, future doctors in pursuit of future careers. They will look a lot like the inaugural class that opened the school 50 years ago.

But this new generation will be working toward much different jobs. They will become trained clinicians, of course, but also stewards of society’s resources, medical economists, efficiency experts, disparities reductionists and big data gurus. Some will possess a CEO’s business acumen.

They will enter a world as complex as the diseases they treat.

With each scientific discovery, there is more to know every year, said Jess Mandel, MD, professor of clinical medicine and former associate dean for undergraduate medical education at UC San Diego School of Medicine. The way medical care is delivered is more complex, requiring more technological interfaces and teamwork. Learning to become a doctor is harder than ever.

“Since 1968, UC San Diego School of Medicine has evolved in innovative ways with its curriculum and training,” said Mandel. “Back then, you mastered a body of knowledge through lectures. Now, medical students need to know more than there is time to teach. Back then, patients took on faith recommendations for care. Now, patients want to understand their treatment based on their physician’s perspective and their own research. These shifts have radically altered medical education.”

Modern Stethoscopes

Not everything about medical school has changed. Students still attend lectures and still dissect human cadavers. To understand anatomy in three dimensions, the body’s structures are best experienced with the eyes and hands. With modern simulation technology, physicians-in-training can now also test procedural skills, including laparoscopy, robotics and endoscopy.

“In medicine today, there is an increasing use of ultrasound beyond radiology,” said Mandel. “It is a critical tool used in many standard-of-care procedures. Ultrasound serves the dual role of teaching anatomy, but also as a point-of-care device for placing central lines, draining abscesses and locating blood clots.

“Our goal has been to introduce ultrasound use to first-year medical students without making it overly disease focused,” said Anthony Medak, MD, associate professor. “They learn ultrasound from many houses of medicine, including emergency and internal medicine, cardiology, radiology, critical care and ob-gyn. Including ultrasound training as part of a pre-clinical medical school curriculum is used in about 30 percent of medical schools in the US.

“We’re not trying to make these doctors professional sonographers. We’re trying to introduce them to a safe, portable, inexpensive tool that can be used in almost any specialty to answer a variety of clinical questions.”

Medack said ultrasound helps students develop a better understanding of anatomy and physiology. The students serve as models, scanning themselves and each other to look at the heart, lungs and musculoskeletal system.

“It’s amazing to see the student’s faces light up when we look at the joints, knees and hands,” said Medak. “With ultrasound, the students can see the tendons of the hand move dynamically as the fingers extend and flex. It comes together visually in real-time.”

“Time and time again, we can see that ultrasound lends to a better patient experience,” he said. “We orient medical students to understand that ultrasound impacts safety. It can help narrow down a differential diagnosis from a dozen possibilities to perhaps three. As these young doctors become more clinically oriented, the utility of point-of-care ultrasound becomes increasingly clear.”

Safety First

“My view is we feel compelled to teach students aspects of cell biology that no one ever uses in practice, and then there isn't enough time for safety and systems,” said Ian Jenkins, MD, professor of medicine.

Jenkins designs coursework for fourth-year medical students with class titles like America’s Cost-Quality Crisis, Quality Improvement 101, How to Kill Your Patient (Our Most Dangerous Medicines) and Teamwork in Healthcare. Students who take these courses are headed into internships, and need to be aware of potential risks inside fast-paced, high-intensity clinical environments.

“When I went to medical school, we never heard the word ‘teamwork,’ Jenkins said. “We were not taught systems or patient safety, and were explicitly told that if something bad happened that it was our fault, and to try harder to be a better doctor.

“The fact is, most doctors are already doing their best. What we are teaching today is that teamwork, quality control and patient safety make a difference, and that doctors who are aware of and engage in these systems are more successful.”

When doctors take care of one patient at a time, they may not think to improve the system of care in which they operate. Jenkins teaches students how to make the physical environment safer. This means understanding software, machines and devices such as electronic medical records and medication ordering systems. To bring the lesson to life, he leads a group project on understanding blood transfusions and blood banks as part of a hospital ecosystem.

“The project helps medical students see what happens when too much blood is ordered and how it impacts the patient’s health and hospital finances,” said Jenkins. “We work through the standard of care to understand the necessity of transfusion, how to implement a hospital protocol for care and how to measure results.”

Jenkins said that he hopes students walk away from the classes seeing that it can be incredibly rewarding to help patients they may never actually meet.

“We teach our medical students that by putting the right policies, protocols and systems in place, you can help more patients than just the ones in front of you.”

Osler Approves

One aspect of medical education at UC San Diego that remains true to its forefathers is an emphasis upon the Oslerian approach to bedside teaching. John Osler (1849-1919) was a Canadian physician credited with transforming medical teaching, including bringing students out of the lecture hall for bedside clinical training. The modern twist is that the doctor is a subject of examination, not just the patient.

With both desire and dread, most medical students are hungry for time with attending physicians. UC San Diego has set up a process for third-year medical students to be observed by a group of highly decorated clinicians.

“The master clinicians directly observe students on the pediatrics clerkship during work, physical examination and clinical reasoning rounds,” said Christopher R. Cannavino, MD, and director of Pediatric Medical Student Education. “They get direct, constructive and unfiltered feedback to shape their doctoring skills. This one-to-one mentoring makes a huge impact.”

The students are not judged or graded. They receive purely informational feedback on things like eye contact, interpersonal skills and working with other medical professionals. The master clinicians silently observe; then privately share with the students how they can improve their clinical skills.

“How do you deliver news to a patient that is less than great? How can you be forthright and upfront while also being compassionate?” said Cannavino. “The clinicians give the students the modeling and even word phrases to communicate better. We fill up their doctor’s bag, so to speak.

“We all have different blind spots, therefore the feedback varies. Some need help synthesizing seemingly disparate symptoms and putting them together to form a diagnosis. It’s not just about getting the right answer. It’s about getting their deductive thinking right.”

Luke Burns, Class of 2018, described the experience: “I'd never encountered anything like this program in any of my rotations, so honestly I didn't know what to expect. It was a genuine privilege to have someone at the senior attending level offer direct feedback. As medical students, we are accustomed to sneaking bits and pieces of feedback from our supervising residents and attendings in between patients. Knowing that my master clinician had been keenly observing me, I was more inclined to take the advice to heart.”

Burns said the program taught him to slow down, speak confidently and organize his presentation in a way that was most useful to the rest of the team.

“This is wisdom I have heard dozens of times before in lectures or conversations with attendings,” said Burns, “but it took several sessions with my master clinician, bouncing ideas back and forth, and dissecting my presentations for me to truly understand.”

Burns learned that the art of medicine is both social science and hard science.

“I have never struggled to communicate with a patient, to be friendly and approachable. The art of medicine is maintaining this social bond while simultaneously gathering data, processing it, forming a differential diagnosis and offering a plan. My mentors in medicine are all individuals who are capable of tackling both these tasks at the same time.”

Who’s Applying

Carolyn Kelly, MD, associate dean for admissions and student affairs, said the school has become increasingly selective in accepting applicants.

“The matriculation rate has gone up with fewer and fewer students being accepted to fill the class,” she said. In 2016, we accepted only 3 percent of the total number of applicants.”

“When we asked students why they were choosing UC San Diego, we learned that the school has a reputation for providing a rigorous education in the science of medicine along with superlative training in the acquisition of clinical skills.”

Mandel agreed: “Our ability to compete with elite institutions for top students has improved in the last decade in a tangible way, and we are proud of that. We are in a situation where our students are spectacular and that becomes one of our greatest recruiting tools. Our students have a credibility with applicants that is higher than that of faculty and administrators.”

The type of applicant accepted has changed.

“We are looking for conscientious students who are academically ready to succeed in medical school,” said Kelly. “We are seeking students with good interpersonal skills, who are ethical and empathic. We look for adaptability and resilience, for students who show promise as future members of a health care team. We hope to uncover their motivation for being part of this profession of service.

“Our students see themselves as members of a larger community facing challenges with health care delivery to all patients. We do our best to help students attain their goals, even if they hit bumps along the way. Academically, we ask a lot of students and the pace is very challenging. Adapting to this pace can be hard. We try to de-stigmatize seeking help. Our mantra is that ‘asking for help is a sign of strength.’ If ever a student feels overwhelmed, there are faculty mentors, advisors and counseling services readily available.

“We are not all supermen and women,” said Mandel. “In order to serve others, physicians need to remain healthy. A depressed physician can’t be a good or compassionate physician. We have to inculcate patterns of behavior that are sustainable over a doctor’s career so that we can be as energetic and compassionate with last patient as the first.”

This is the second in a four-part series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the UC San Diego School of Medicine. See part 1 here.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.