By:

- Heather Buschman

Published Date

By:

- Heather Buschman

Share This:

School of Medicine Turns 50

1968 was an unforgettable year.

North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive. Richard Nixon was elected president. The Beatles released the White Album. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Upon hearing the news a few hours later, just as he was about to give a scheduled speech, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy responded with a powerful extemporaneous eulogy in which he called upon those who would “tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

Far above it all, Apollo 8 orbited the moon, the first manned spacecraft to do so.

Back on Earth, Bill Jessee had a tough decision to make. He had been accepted to two medical schools: UCLA and UC San Diego. The problem was UC San Diego didn’t actually have a medical school yet.

“Sure, UCLA would’ve been a safe bet,” said Jessee, MD. “But their acceptance letter was a just mimeograph — a stenciled copy, the precursor to the photocopy. In contrast, from UC San Diego I received a personal letter of acceptance from Hal Simon, the associate dean for student affairs, himself. I knew then that UC San Diego would give me the kind of personal attention I wouldn’t have found elsewhere.”

Starting from scratch

Jessee decided to take a chance on the new school, despite its lack of history or reputation. He started medical school at UC San Diego that fall with 46 others in the charter class. From the beginning, the school attracted risk-takers like Jessee, who welcomed the chance to be a part of a new type of medical education.

One of these innovators was the school’s first dean, Joseph Stokes III, MD. In addition to his work in medical education, Stokes led research in preventive medicine, infectious diseases and cardiovascular disease, particularly as they related to the relatively new field of genetics.

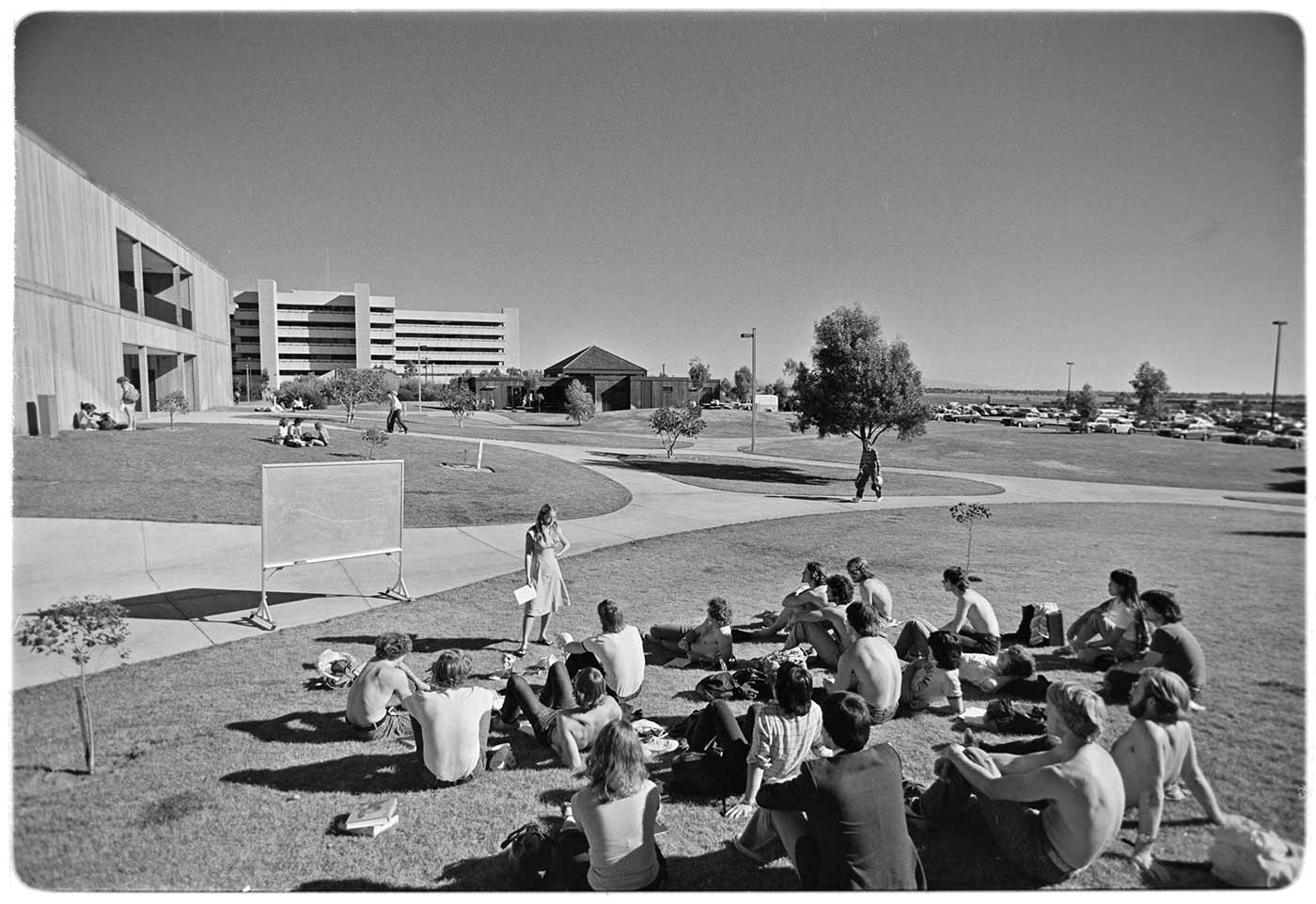

Perhaps due to his own varied, interdisciplinary research interests, Stokes and the other founding faculty wanted to build a school that didn’t just have medical students memorize disease symptoms and their treatments from a textbook. They wanted to provide a medical education strongly rooted in the basic sciences and the underlying causes of disease. At the same time, they didn’t want students who did nothing but sit in lectures for their first two years.

In a 1964 university press release announcing his appointment, Stokes said he hoped the new medical school would attract a special type of student who is “able and willing to innovate, investigate, and educate…So greatly has scientific investigation advanced medicine that today’s generation of doctors can hardly speak to the doctors of a generation ago. The research output of the medical school is every bit as important as the number of students who are graduated.”

But to attract those special students like Jessee, Stokes and team first needed to build a faculty of the best and brightest. So they rolled up their sleeves, built bridges with other science departments across the UC San Diego campus and traveled the country to recruit more like-minded educators, clinicians and scientists.

One of Stokes’ first recruits was Eugene Braunwald, MD, who served as founding chair of the Department of Medicine. Braunwald left a comfortable academic life at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to take a chance on a new endeavor — a new school of medicine that was just one building in the middle of nowhere and a newly acquired community hospital a ways down the freeway in Hillcrest.

“I was attracted by the concept of a new school starting from scratch, with interesting ideas about education that still had to be fleshed out,” Braunwald said. “The fact that we started with an empty slate attracted me—no students, no buildings and sort-of a hospital. Things were primitive. It was really a desert, literally and figuratively. But it was an exhilarating experience.”

Others quickly followed.

Braunwald’s own wife, Nina Starr Braunwald, MD, was among this intrepid group. She was the first woman to be board certified in cardiac surgery. In 1960, at the age of 32, she had led the surgical team at the NIH that implanted the first successful artificial mitral human heart valve replacement, which she had also designed and built. At UC San Diego School of Medicine, she was acting director of the Division of Cardiac Surgery. The year the school admitted the first class, she was cited in a publication called “American Men of Science.”

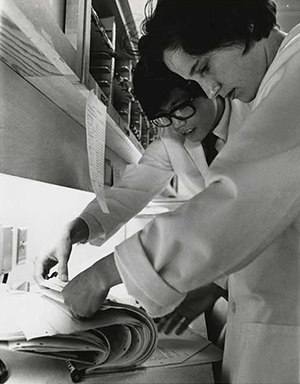

And there were many more visionaries who came in those early years: Robert Burr Livingston, MD, the first professor and chair of the Department of Neurosciences, was credited with building the first computerized map of the human brain. John S. O'Brien, MD, second chairman of the same department, discovered the genetic cause of Tay-Sachs disease and developed the first tests for the disorder. Daniel Steinberg, MD, PhD, founding head of the Division of Metabolic Diseases, was one of the first to determine that high cholesterol is a major contributing factor in the development of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, MD, who founded the Rancho Bernardo Heart and Chronic Disease Study in 1972, a landmark project that tracked thousands of participants over more than 40 years.

Re-defining medical education

From the beginning, Stokes and the other founders believed the basic science part of the medical school curriculum didn’t need to be taught in isolation in the School of Medicine—they thought it should be taught by other campus departments, such as the Department of Biology (now the Division of Biological Sciences). David Bonner, PhD, founding chair of the Department of Biology, once said, “There is no such thing as basic versus applied science; there is only good or bad science.”

That philosophy led to what’s known as the “Bonner Plan.” Eventually, UC San Diego medical students would take graduate-level classes in biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology alongside graduate students devoted to those fields. Second-year medical students took their anatomy and pathology courses with clinical faculty, but could continue working in labs and taking electives in general campus graduate departments.

While the Bonner Plan set the stage for an unparalleled intermingling of basic sciences in a medical school, Clifford Grobstein, PhD, the school’s dean when the first class entered in 1968, continued that tradition.

“Dr. Grobstein was a cellular physiologist and it was unusual at that time to have a medical school dean who was not a physician,” Jessee said.

But it was consistent with the concept of a strong basic science foundation.

“We’ve always tried to do things a bit differently,” said John West, MD, PhD, DSc, a pioneer in physiology who has been at the School of Medicine almost since the first day. He still teaches today.

“From day one, medical school students are taught by clinical scientists and working researchers. There’s a deep, long-standing, inextricable connection here between the science and the art of medicine. The curriculum has always been about making it real—and about making really good doctors and scientists.”

But Stokes, Grobstein and their faculty recruits didn’t stop there.

“One of the problems in American medical education at the time was that medical schools were divided into two years in classroom, two years in in the clinics,” Braunwald said. “These two had little to do with each other, and yet they are intellectually intertwined. We saw that as an opportunity for making a change.”

So Stokes, Braunwald and the other founding faculty integrated both worlds. They introduced students to patients the first week they arrived. And they expected every student to conduct a research project suitable for publication before graduation.

“We stood the curriculum on its head—we intermingled clinical and science work like nobody else was doing at the time,” Braunwald said. “UC San Diego was a model for what everyone else is doing now.”

Bending the rules

Many of the early faculty and students did things differently in other ways, too.

“To better understand the hospital in Hillcrest, I lived in a patient room for six weeks,” Braunwald said.

Braunwald moved to San Diego at the end of April 1968, but his wife and children stayed behind to finish out the school year. Instead of living in a motel during the interim, he found an empty room in the hospital and camped out. He even brought in a desk and set up a small office.

“The experience gave me tremendous insight,” he said. “For example, I would go down to the Emergency Department at 3 a.m. and poke around. I’d discover people who should’ve been there, but weren’t, and got that fixed up. I often went to the X-ray department to see how quickly films were being read. I began to see a lot of things other department chairs didn’t. They make their rounds, of course, but then you only see things in a very pasteurized way, not the real McCoy. In those six weeks I got a better sense of the hospital, its strengths and weaknesses, and then I worked on making improvements throughout the subsequent years.”

The students also helped shape the School of Medicine’s curriculum and values.

“It was a selling point that if you want to do something new, there’s no precedent to say you can’t,” Jessee said. “We had a lot of flexibility to pursue whatever interested us.”

He put that philosophy to the test, too. He initially decided not to do a surgery rotation, and instead focus on pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology.

“But that provoked a faculty meeting,” Jessee laughed. “In the end, they had to modify the school’s policy to meet California requirements, which included rotations in surgery.”

If standardized exams are a measure of success, the Bonner Plan and the vision of the founding faculty worked: The school’s second class of 48 students ranked #1 in the U.S. on the 1971 board exams.

Looking ahead

While the art and science of medicine have evolved since 1968, the School of Medicine’s goal is constant: Create physicians who are as compassionate as they are brilliant.

“We take a lot of things for granted,” said Maria Savoia, MD, the current dean for medical education. “Our collaborative and innovative spirit have become so commonplace that it’s just a part of the landscape. Sometimes you don’t even realize how special the things we do are until you’re out in the world at other places and hear about how a school or researcher is ‘innovating’ by doing something we’ve already been doing without even thinking about it. We just do it. And we have been doing it since the beginning.”

Medical students put their procedural, teamwork and communication skills to the test with a manikin in the Simulation Training Center at UC San Diego School of Medicine, 2017.

Today, the UC San Diego School of Medicine is routinely ranked in the top 20 medical schools in the nation, for both research and primary care, by U.S. News & World Report; it also continues to attract adventurous students.

This is the first in a four-part series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the UC San Diego School of Medicine. See part 2 here.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.