Search for the Higgs Boson Turns up a New Particle

UC San Diego has played a major role in the search for the Higgs Boson at the Large Hadron Collider

By:

- Susan Brown

Published Date

By:

- Susan Brown

Share This:

Article Content

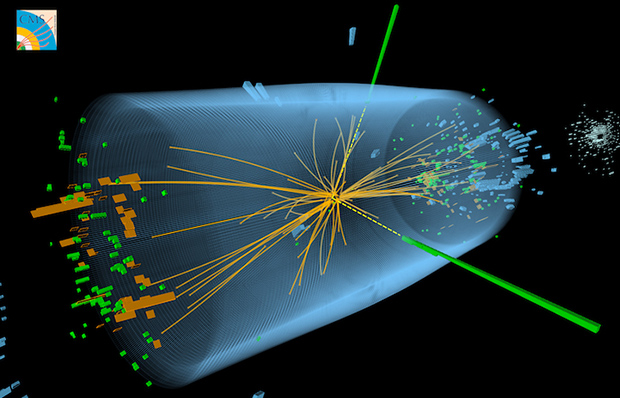

A pair of photons (dashed yellow lines and green towers) recorded by the CMS detector when two protons smashed within it earlier this year. The event shows characteristics expected from the decay of the standard model Higgs boson to a pair of photons but could also be due to other physical processes. Image: CMS/CER

Physicists have observed a new particle that so far matches the signature they expect from the long-sought Higgs boson. But they have not yet collected enough information about the new particle to confirm that it really is the one they seek.

The CMS collaboration, one of two independent teams looking for the Higgs with separate detectors, reported a mass for the new particle of 125 giga electronvolts at a seminar held at CERN July 4. They calculated the chance of that being a false observation at one in 3.5 million.

“This is a historic moment in science. It is amazing how quickly we have confirmed the evidence of a signal at 125 GeV that we reported just six months ago,” said Vivek Sharma, professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego who led the search for Higgs boson in the CMS experiment at CERN from 2010 to 2011 and is now a member of the CMS Editorial board.

When the collider crashes protons together at nearly the speed of light, Higgs bosons should appear for a fleeting moment then break apart right away. Detecting the Higgs depends on tracing the trajectories of the resulting debris and understanding other physical processes that could leave similar trails.

The Standard Model, a theory that describes subatomic phenomena with remarkable accuracy, predicts that a Higgs boson of a particular mass will decay to one of several specific combinations of particles. One possibility is a pair of photons, which create flickers of light as they strike lead tungstate crystals that form one layer of the CMS.

UC San Diego professor James Branson’s group has studied how two photons would arise from a decaying Higgs boson and from other events, for more than a decade. They helped optimize the detector’s ability to precisely measure the photons’ energy and trajectories, information the CMS team uses to determine what exactly happened, including the mass of the disintegrated particle. The most precise measurement of the mass of the new particle came from this two-photon “channel.”

The Higgs could also decay into a pair of Z bosons, which in turn decay into other particles (pairs of electrons or muons). Sharma’s group searched for the Higgs boson in this events, which while rare, are considered “golden” because they provide a unique signature of the Higgs boson. Their observation of a cluster of these events peaking near 126 GeV plays a crucial role in the observation of this new particle.

Both the two-photon and two-Z-boson channels offer excellent opportunities to pin down the mass of the Higgs boson.

The research groups of UC San Diego faculty members Vivek Sharma, Frank Würthwein and Avi Yagil, worked on yet another trail, the decay of a Higgs boson into two W bosons, and event that can indicate that a Higgs boson may have appeared, but doesn’t provide information about its mass.

A rival team of scientists working independently to analyze data collected by a separate instrument, called ATLAS, positioned at a different location within the collider’s tunnel, report similar results, though their estimate of the particles mass was a bit higher at 126 billion electronvolts, about the mass of an iodine atom.

To arrive at a more definite answer on whether the Higgs boson exists in the form predicted by the Standard Model, or as something more exotic, physicists will need to sift through the debris from many more collisions to precisely measure the properties of the particle they have found. The results so far are tantalizing enough that CERN will extend the current run by three months, tripling the amount of data, in the hope of settling the question by the end of this year.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.