Scientists Show Ancient Village Adapted to Drought, Rising Seas

Underwater excavation reveals human resilience through Neolithic-period climate change

Story by:

Published Date

Article Content

Around 6,200 BCE, the climate changed. Global temperatures dropped, sea levels rose and the southern Levant, including modern-day Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, Lebanon, southern Syria and the Sinai desert, entered a period of drought.

Previously, archaeologists believed that this abrupt shift in global climate, called the 8.2ka event, may have led to the widespread abandonment of coastal settlements in the southern Levant. In a recent study published with the journal Antiquity, researchers at UC San Diego, the University of Haifa and Bar-Ilan University share new evidence suggesting at least one village formerly thought abandoned not only remained occupied, but thrived throughout this period.

“This [study] helped fill a gap in our understanding of the early settlement of the Eastern Mediterranean coastline,” said Thomas Levy, a co-author on the paper, co-director of the Center for Cyber-Archaeology and Sustainability (CCAS) at the UC San Diego Qualcomm Institute (QI), inaugural holder of the Norma Kershaw Chair in the Archaeology of Ancient Israel and Neighboring Lands in the Department of Anthropology, and a distinguished professor in the university’s Graduate Division. “It deals with human resilience.”

Signs of life

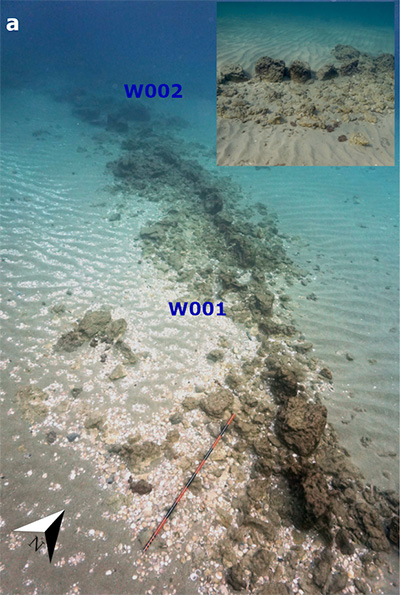

The village of Habonim North was discovered off Israel’s Carmel Coast in the mid-2010s and later surveyed by a team led by the University of Haifa’s Ehud Arkin Shalev.

Prior to its excavation and analysis, there was scant evidence for human habitation along the southern Levantine coast during the 8.2ka event. The dig, which took place during the COVID-19 lockdown and involved a weeks-long, 24/7 coordinated effort between partners at UC San Diego and the University of Haifa, was the first formal excavation of the submerged site.

Led by Assaf Yasur-Landau, head of the Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa, and Roey Nickelsberg, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Haifa, the international team excavated the site using a combination of sediment dredging and sampling, as well as photogrammetry and 3D modeling. Team members uncovered pottery shards or “sherds”; stone tools, including ceremonial weapons and fishing-net weights; animal and plant remains; and architecture.

Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers tested the recovered bones of wild and domesticated animals; the charred seeds of wild plants; crops like wheat and lentils; and weeds that tend to accompany these crops. Their results traced these organic materials back to the Early Pottery Neolithic (EPN), which coincided with both the invention of pottery and the 8.2ka event.

Habonim North’s pottery sherds, stone tools and architecture likewise dated activity at the site to the EPN and, surprisingly, to the Late Pottery Neolithic, when the village was thought to have been abandoned.

As for how the village likely weathered the worst of the climate instability, the researchers point to signs of an economy that diversified from farming to include maritime culture and trade within a distinct cultural identity. Evidence includes fishing-net weights; tools made of basalt, a stone that does not naturally occur along this part of the eastern Mediterranean coast; and a ceremonial mace head.

“[Our study] showed that the Early Pottery Neolithic society [at Habonim North] displayed multi-layered resilience that enabled it to withstand the 8.2ka crisis,” said Assaf Yasur-Landau, senior author on the paper. “I was happily surprised by the richness of the finds, from pottery to organic remains.”

Through 3D “digital twin” technology and the Haifa – UC San Diego QI collaboration, the researchers studying Habonim North have been able to recreate their excavation, virtually, and 3D-print artifacts, opening the path to further study. The team previously received an Innovations in Networking Award for Research Applications from the non-profit organization CENIC for “exemplary” work leveraging high-bandwidth networking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Shifting the focus to resilience

Although scientists debate the cause of the 8.2ka event, some speculate that it began with the final collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet, which shaped much of the North American landscape in its retreat from modern-day Canada and the Northern United States.

As it melted, the ice sheet would have changed the flow of ocean currents, affecting heat transport and leading to the observed drop in global temperatures.

For the authors behind the study, the discovery of lasting and evolving social activity at Habonim North through this period of climate instability indicates a level of resilience in early Neolithic societies. Many of the activities uncovered at the village, including the creation of culturally distinct pottery and trade, formed the basis for later urban societies.

“To me, what’s important is to change how we look at things,” said Nickelsberg. “Many archaeologists like to look at the collapse of civilizations. Maybe it’s time to start looking at the development of human culture, rather than its destruction and abandonment.”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.