Researchers Reveal Behaviors of the Tiniest Water Droplets

UC San Diego, Emory U. Team Create New Simulations on SDSC’s ‘Gordon’ Supercomputer

By:

- Jan Zverina

Published Date

By:

- Jan Zverina

Share This:

Article Content

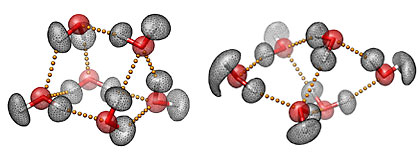

Three-dimensional representations of the prism (left) and cage (right) structures of the water hexamer, the smallest drop of water. The mesh contours represent the actual quantum-mechanical densities of the oxygen (red) and hydrogen (white) atoms. The small yellow spheres represent the hydrogen bonds between the six water molecules. Characterizing the hydrogen-bond topology of the water hexamer at the molecular level is key to understanding the unique and often surprising properties of liquid water, our life matrix. Images courtesy of Volodymyr Babin and Francesco Paesani, UC San Diego.

A new study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and Emory University has uncovered fundamental details about the hexamer structures that make up the tiniest droplets of water, the key component of life – and one that scientists still don’t fully understand.

The research, recently published in The Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), provides a new interpretation for experimental measurements as well as a vital test for future studies of our most precious resource. Moreover, understanding the properties of water at the molecular level can ultimately have an impact on many areas of science, including the development of new drugs or advances in climate change research.

“About 60% of our bodies are made of water that effectively mediates all biological processes,” said Francesco Paesani, one of the paper’s corresponding authors who is an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UC San Diego and a computational researcher with the university’s San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC). “Without water, proteins don't work and life as we know it wouldn't exist. Understanding the molecular properties of the hydrogen bond network of water is the key to understanding everything else that happens in water. And we still don't have a precise picture of the molecular structure of liquid water in different environments.”

Researchers know that the unique properties of water are due to its capability of forming a highly flexible but still dense hydrogen bond network which adapts according to the surrounding environment. As described in the JACS paper, researchers have determined the relative populations of the different isomers of the water hexamer as they assemble into various configurations called ‘cage’, ‘prism’, and ‘book’.

The water hexamer is considered the smallest drop of water because it is the smallest water cluster that is three dimensional, i.e., a cluster where the oxygen atoms of the molecules do not lie on the same plane. As such, it is the prototypical system for understanding the properties of the hydrogen bond dynamics in the condensed phases because of its direct connection with ice, as well as with the structural arrangements that occur in liquid water.

This system also allows scientists to better understand the structure and dynamics of water in its liquid state, which plays a central role in many phenomena of relevance to different areas of science, including physics, chemistry, biology, geology, and climate research. For example, the hydration structure around proteins affects their stability and function, water in the active sites of enzymes affects their catalytic power, and the behavior of water adsorbed on atmospheric particles drives the formation of clouds.

“Until now, experiments and calculations on small water clusters have agreed very well up to the pentamer (in chemistry, meaning molecules made of five monomers) but the energetic ordering of the low-lying isomers of the hexamer has always been controversial,” said Paesani.

Added corresponding author Joel M. Bowman, with Emory University’s Department of Chemistry and the Cherry L. Emerson Center for Scientific Computation: “Ours are the first simulations that use an accurate, full-dimensional representation of the molecular interactions and exact inclusion of nuclear quantum effects through state-of-the-art computational approaches. These allow us to accurately determine the stability of the different isomers over a wide range of temperatures ranging from 0 to 150 Kelvin, (almost minus 460 degrees to about minus 190 degrees Fahrenheit).”

While the prism isomer was identified as the global minimum-energy structure, the quantum simulations predicted that both the cage and prism isomers are present in nearly equal amounts at extremely low temperatures, researchers found. As the temperature increased, more cages, and then book structures, began to appear.

Researchers used SDSC’s new data-intensive Gordon supercomputer as well as SDSC’s Triton compute cluster to conduct the data-intensive simulations.

“Our simulations took full advantage of Gordon distributing the computations over thousands of processors,” said Volodymyr Babin, a researcher with UC San Diego’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. “That kind of parallel efficiency would be hardly achievable on a commodity cluster. The scalability of our computational approach stems from the combination of a state-of-the-art simulation technique (replica-exchange) with path-integral molecular dynamics.”

Babin said the team is currently working on extending this methodology to study the microscopic origins of the unusual properties of liquid water and ice aiming to assess quantitatively the role played by nuclear quantum effects in the topology of the water phase diagram. This project involves a huge number of data-intensive quantum chemistry computations that are only feasible on supercomputers of the same class as Gordon, he added.

The JACS paper is called “The Water Hexamer: Cage, Prism or Both. Full Dimensional Quantum Simulations Say Both,” and also included Yimin Wang from Emory University, who developed the potential used in the simulations. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through grants CHE-1111364 and CHE-1038028, NSF award TG-CHE110009 for computing time on the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), and awards from the CCI Center for Aerosol Impacts on Climate and the Environment.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.