By:

- Amanda Rubalcava

Published Date

By:

- Amanda Rubalcava

Share This:

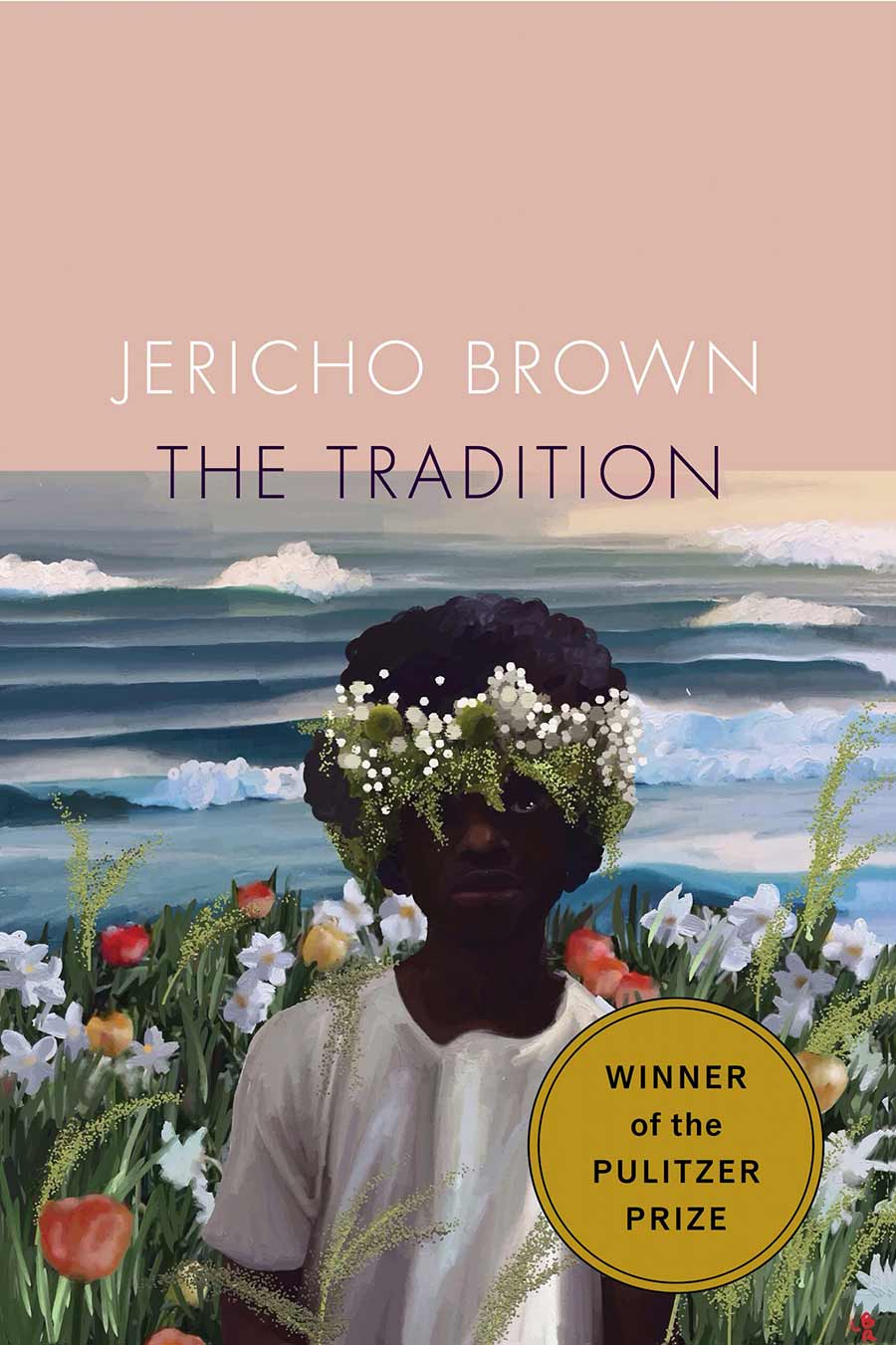

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Poet Brings “The Tradition” to Campus

Jericho Brown to visit UC San Diego for reading and Q&A

Whenever poet Jericho Brown feels like he is chosen to experience something, he jumps into that moment as much as he can. He felt this way when he was awarded the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry—a unique time amid a global pandemic when his words had the opportunity to help heal readers. Next month, he will be sharing these same words with the UC San Diego campus community as part of a poetry reading event at Price Center Theater.

On May 5, Brown will be visiting campus to read from his winning work “The Tradition” and take part in a moderated Q&A session. The event is hosted by the Humanities Program in celebration of the inaugural year of One Book Revelle, which unites readers and builds community around a single title. Guests can register to attend the poetry reading, in person or remote, on the event webpage.

“The Tradition” is Brown’s third book and is recognized by the Pulitzer Board as “a collection of masterful lyrics that combine delicacy with historical urgency in their loving evocation of bodies vulnerable to hostility and violence." We spoke to Brown to learn about his influences, how it felt to win a Pulitzer during the pandemic, his connection to San Diego and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Can you share a bit about where you grew up? Did your roots shape your work?

A. I grew up in Shreveport, Louisiana. I do think my work is quite southern in its vernacular. I definitely make use of the kinds of phrasing and the kinds of talk that I heard as a kid growing up.

I also grew up in a family where there was a lot of partying on Friday and Saturday nights. But no matter how much partying there was, people did not miss church on Sunday morning. I think the Black church in particular has a lot to do with how I think about poems—how I think about performance, how I think about everything that can be staged, or everything that can be given over as art. Just the structure of the order of service at church probably has a lot to do with the way I think about the structure of a poem or a book.

Q. Was there a definitive moment that you knew your path was to become a poet?

A. I don't think there was a definitive moment, but I do think I have moments little by little. I think I still have those moments—sometimes I think it is over for me now, and then I'll finish a poem!

When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time in libraries. I think seeing poems on the page and then hearing them recited every once in a while at church is what inspired me to do them. I knew that I had feeling from poems. I knew that while I read Langston Hughes or Sylvia Plath, I would feel things. I wanted to make that feeling available to other people.

Q. What are some of your influences?

A. I'm really influenced by music. There is something about Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, and the music that was coming out of Motown in the 60s and 70s that has been really influential to me. I think I learned from it how to organize a piece of art—how you create excitement, how you create a mood, how you create sadness in a listener.

I’m also influenced by film. I think my last book would not have been written if I hadn’t seen Moonlight like 17 times. I think there was something about it that changed what I was able to do in my own writing.

Q. How was the experience of being awarded a Pulitzer? What did the accolade mean to you personally?

A. It was very exciting for me. We were in the pandemic when I found out, so I really wasn't leaving my house and nobody was coming over. I found out about the Pulitzer in a kind of isolation that I think is very different from probably how anybody else found out about their Pulitzer in previous years.

So, I didn't get to party, and yet, I had what still seems to me like a huge responsibility. I was the pandemic poet who won the Pulitzer! I had a lot of work to do over Zoom and it was work that I was glad to do.

I felt like, “Oh, we're in the midst of a moment and poetry is always a help and a salve.” I felt like I had been chosen for this moment. And, when I get the feeling that I am chosen for something, I just jump into it as much as I possibly can.

Q. Do you think that the timing of when you won the Pulitzer changed how the audience reacted to your work?

A. I think a lot of people discovered poetry during the pandemic and I think it was the best time for them to discover it. I think poetry fulfills a need we don't know we have.

During the pandemic—because people were isolated and were dealing with things that were very new and very scary—I think people became aware that poetry could somehow hold them through this moment.

Q. When writing ‘The Tradition,’ did you have any specific hopes for what the audience would take away after reading the collection?

A. It's an interesting question—yes and no. When working on a book, it’s actually important for you to not think about the readers. If you do, you'll end up trying to write a book that satisfies what you imagined to be what people want.

Instead, I think it's a good idea to write poems and books that really satisfy what your needs are and what you want from poetry. I also think it is impossible not to have hope that you touch somebody. I am really glad that there are so many people who are interested in “The Tradition,” but beyond that, I have to let it go.

I’m grateful that something I made makes a difference in somebody else's life. I really believe that about art—it makes a difference in our lives that we can't tally up. The value of it is too great. So, we can't do what we do for people and yet, the act of writing is an act of reaching out

Q. Your work features a new poetic form called the duplex. Can you share a bit about this?

A. I wrote the duplex because I was thinking about these three different forms: the ghazal, the sonnet and the blues. I just wanted to own those forms a little more because I feel close to all of them. I wanted to own them in a way where their identity was made full in a single poem.

I wanted to do that because I would like my identity to be made full in a single body, you know? I'm always getting called to the mat about my own identity—people want me to be 60% Black, 20% queer, 7% southern, and so on, and it gets complicated. I would like to be everything I am 100% without this very false idea that I am somehow at war with myself. I think I am all those things whole.

Q. What does your writing process look like?

A. I'll write anytime, anywhere if something comes to me. To be quite honest, sometimes it just looks like changing a period to a dash in one day. I get obsessed over the smallest things.

I wish it looked like this more often, but sometimes it looks like me starting with the first line and ending with the last line in one sitting and getting a first draft. Very often, it looks like looking back at old work and taking the good things from failed poems and putting them with other good lines and good pieces from other failed poems.

Q. Can you share a bit about your connection to San Diego?

A. I used to live there! I used to teach at the University of San Diego—it was my first full-time job as a college professor. While I was there, my first book “Please” came out and I started writing my second book, “The New Testament.” I was there for five years. I have some good friends and colleagues there and I always look forward to coming back.

I'm glad I got to live there because it gave me a new landscape to work with. It seems small and simple, but if a poet spends enough time in a place, what they have to say and the elements that appear in their poems are different. So when I was in San Diego, suddenly there were canyons and sand in my poems, and that hadn't happened before.

Q. Finally, what advice would you give to our campus community of student writers?

A. I think the best advice I can give is to read in a way that allows you to see beyond the subject.

We know it's possible to write a very unsuccessful poem about kittens. We know it's possible to write a very beautiful poem about kittens. So, my advice is that you figure out, in any poem, what went right. Try to figure out, quite literally, how that happened. How were you led to fall in love with the poem? Make use of those same strategies in your own poems.

To learn more about the upcoming poetry reading with poet Jericho Brown, please visit the event website. The free event is hosted by Revelle College and the Humanities Program. It is in partnership with UC San Diego New Writing Series, Office of the Vice Chancellor for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, Black Resource Center and the LGBT Resource Center.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.