Neuronal Structures Associated with Learning and Memory Sprout In Response to Novel Molecules

Drug candidates protect neurons against damage from substance implicated in Alzheimer’s disease

Published Date

Article Content

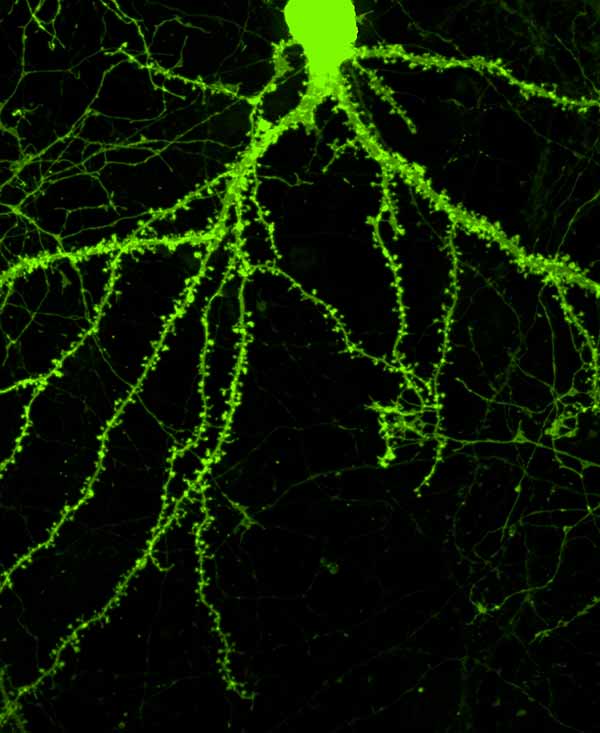

Tiny thorns along the branches of this neuron are dendritic spines, which form the receiving end of synapses. Treatment with a novel compound induced the cell to sprout 20 to 25 percent more spines than a normal, untreated neuron. Image credit: Jessica Cifelli

Chemists at the University of California San Diego have designed a set of molecules that promote microscopic, anatomical changes in neurons associated with the formation and retention of memories. These drug candidates also prevent deterioration of the same neuronal structures in the presence of amyloid-beta, a protein fragment that accumulates in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease.

The study looked at the effect of drug candidates on the density of tiny thornlike structures called dendritic spines that bristle along the branching processes of neurons and receive incoming signals.

"Problems with learning and memory in many neurodegenerative and neurodevelopment disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and certain forms of autism or mental retardation involve either loss or misregulation of dendritic spines," said Jerry Yang, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry who led the work. "The compounds we have developed may offer the possibility to compensate, or ideally preserve, neuronal communication in people suffering from problems with memory."

When the researchers treated neurons from a part of the brain critical to forming and retrieving memories with their new compounds they saw an increase in the density of dendritic spines. The new compounds also prevented the loss of these spines that occurs in the presence of amyloid-beta, the substance that forms amyloid plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, the team reports in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

The greater the concentration of the drug candidate, the greater the density of spines within the range of doses the team tested. The effect is also reversible: once the compounds were washed away, the spines receded within 24 hours.

Earlier versions of these compounds, also developed by Yang's research group, improved memory and learning in normal mice and a mouse model for Alzheimer's disease, but were too toxic to pursue as drug candidates.

Jessica Cifelli, a graduate student in Yang's group, worked out a way to keep the part of the molecules that they believe promoted the growth of dendritic spines, but alter the chemical features that impart toxicity. These novel compounds, called benzothiazole amphiphiles, are new tools to study relationship between dendritic spines and cognitive behavior.

We know from a wealth of prior research that spine densities on neurons change over time and that increases in the densities correlate with improved memory and learning. As potential drugs, benzothiazole amphiphiles could be useful for combatting spine loss in neurodegenerative disease, or possibly for general cognitive enhancement.

Co-authors include Lara Dozier, Tim Chung and Gentry Patrick. UC San Diego's Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, funded by the National Institute on Aging, partially supported this research.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.