Neil Smith Charts the Future of Cyber-Archaeology

Story by:

Published Date

Article Content

Neil Smith volunteered for his first field expedition abroad when he was 19. Then a sophomore in the UC San Diego Department of Anthropology, he responded to Professor Thomas Levy’s call for students interested in an excavation in southern Jordan. What Levy needed, above all, was someone who could transform handwritten data into digital maps of dig sites.

Although Smith had never undertaken this type of work, he had plenty of experience tinkering with computers—his father worked for IBM and often brought computers home. In preparation for the trip to Jordan, Smith learned geographic information systems (GIS) with Mark Waggoner at the UC San Diego Geisel Library to provide the skillset Levy needed.

Although Smith was one of more than 100 students and staff who ultimately joined Levy on the excavation, Smith quickly set himself apart.

“He seemed to be a typical California kid,” Levy said, “but had an unusual passion to immerse himself totally in exploring the historical roots of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) from a scientific perspective, in the lands where it took place.”

Today, Levy and Smith co-direct a center dedicated to studying, digitally preserving and sharing endangered cultural sites around the Eastern Mediterranean. Called the Center for Cyber-Archaeology and Sustainability (CCAS) at the UC San Diego Qualcomm Institute (QI), the initiative combines engineering, computer science and the natural sciences to forge an exciting new branch of an established field.

The Past, Modernized

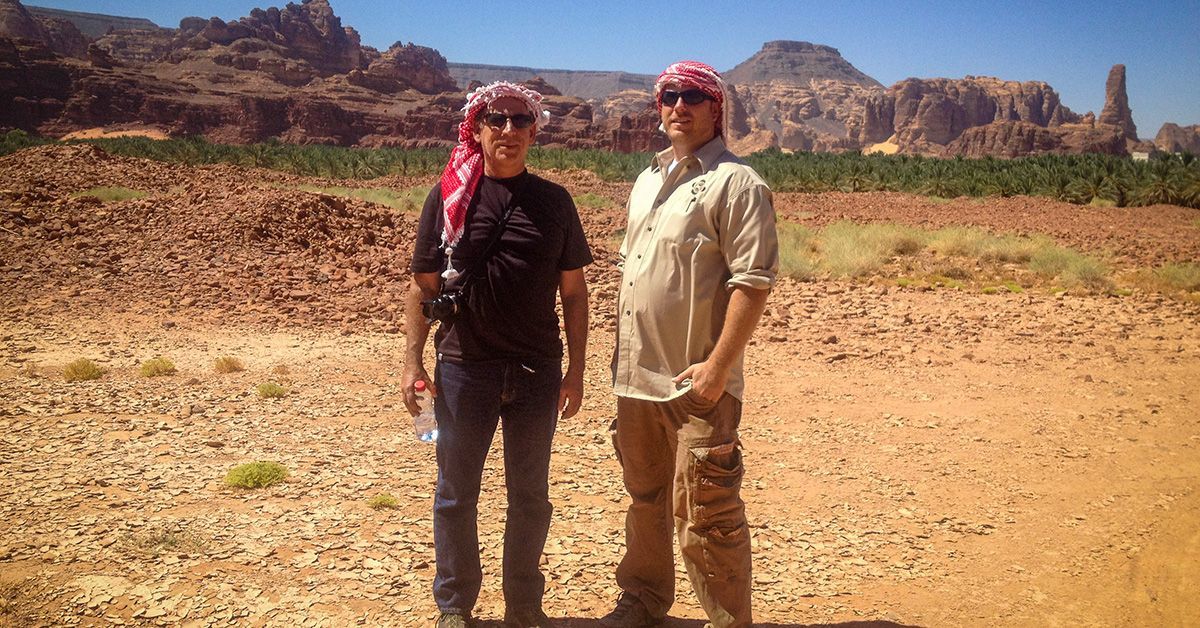

When Smith joined the expedition to Wadi Faynan, Jordan, in 1999, Levy was one of a number of scientists championing an emerging field he calls “cyber-archaeology.” The approach uses GIS and other computer- and math-based technologies and techniques to study the archaeological record in a shared immersive, digital environment.

Smith saw the new discipline as a way to combine his fascination with both computer science and the Levant, a region that includes Israel and Jordan.

“Ancient Israel, or what we call the southern Levant, is not just the center of the Jewish faith, but also the Christian, Muslim and many other faiths,” said Smith. “It’s an essential cradle of society and cultures that have emerged over the years. It intrigues me to see how such a small part of the world has impacted culture, beliefs and our understanding of our past, globally.”

Throughout his undergraduate years, Smith joined Levy and others on expeditions into the Southern Jordan highlands, where previous research had uncovered ceramic shards dating back to the late Iron Age. These sites had helped archaeologists and historians build a timeline of the rise of Edom, a Biblical and historical kingdom that encompassed Wadi Faynan and crossed into modern day Israel and Egypt. Historians estimated the kingdom rose to prominence around the time the ceramics were created.

Yet, when Levy and Smith descended to the Faynan lowlands for Smith’s graduate work in 2002, they uncovered results that told a different story.

Within the arid stretch of Faynan’s lowlands lay Khirbat en-Nahas, a 3,000-year-old copper production site marked by hillocks of inorganic waste and the ruins of an Iron Age fortress. Smith—newly married to Kristiana Bobczynski, a historian and photographer who joined him on his travels—and Levy led further excavations and performed radiocarbon dating on charcoal and seeds found associated with ancient ceramics and other findings from the site. Their results pushed the rise of Edom as an organized kingdom back to the 9th or 10th century, approximately 200 years earlier than previously estimated.

For his dissertation, Smith compared ceramics recovered from the full breadth of Southern Jordan, from its plateaus to Khirbat en-Nahas. With the aid of a doctoral dissertation grant from the National Science Foundation, he and Kristiana moved to Jordan full-time to ease traveling between dig sites.

While there, Smith established a “portable” digital archaeology lab in an apartment above a fruit store. Soon, he had gathered a community, including other excavation directors, who conferred with him on archaeology’s transition into the digital realm.

An Experimental Approach

“I saw archaeology as an avenue to discover new data and information about people we know very little about from the Hebrew Bible. That’s what really intrigued me—that we could go beyond what history has written."

Following his doctoral work and defense back in San Diego, Smith took up a position with Thomas DeFanti, a research scientist with the UC San Diego branch of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, later renamed the Qualcomm Institute in recognition of Qualcomm Inc.’s philanthropic support. DeFanti specialized in scientific visualization, a branch of science that transforms data into visual encodings that researchers can then study to better learn about their subjects.

In years prior, DeFanti had formed a partnership with the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, and established a scientific visualization lab on the university campus in 2009. On Smith’s first trip accompanying DeFanti to KAUST in 2012, Smith’s work drew the eye of Helmut Pottmann, director of the KAUST Visual Computing Center. Before the trip was done, he’d been offered a job as a research scientist in Saudi Arabia.

“I was really excited, but it was also kind of shocking,” said Smith. “I didn’t think that I’d be offered a position on the spot. I came home and told my wife, ‘I’ve been offered a job in Saudi Arabia, what do you think?’ And she said, ‘This sounds like another adventure and a rare open door we should step through.’”

Again, Smith and his wife gathered up their small family and moved to another country. Their new community was open and warm, and offered a sense of hospitality that Smith says he had encountered only in the Middle East.

At KAUST, he met Luca Passone, a then-Ph.D. student pursuing the earth sciences and engineering. Passone was in the process of capturing 3D images of the KAUST Grand Mosque, a sweeping complex of white and blue stone, using drones. Smith, who was experimenting with photogrammetry or structure-from-motion, a technique in which hundreds of data points make up 3D images, offered his own expertise.

Together, they captured the entirety of the mosque within the span of five minutes. Their final product was so lifelike that it caught the attention of the vice mayor of Jeddah on a visit to the university. To their surprise, he requested their aid in documenting Al-Balad, a historic stretch of Jeddah that dates back to the seventh century, as part of its consideration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The experience showed Smith that there was a need for rapid data capture and 3D modeling beyond the world of research. Together with Passone and KAUST Senior Research Scientist Mohamed Shalaby, he applied for and secured seed funding to establish a startup called FalconViz.

At its core, the company uses the rapid capture of data via drones to digitize the world for clients ranging from public officials to NEOM, a region of futuristic cities and resorts under construction in northern Saudi Arabia. The firm’s goal is to provide digital twins of real-world sites and buildings for infrastructure projects, public safety and more.

Jump-Start in a New Direction

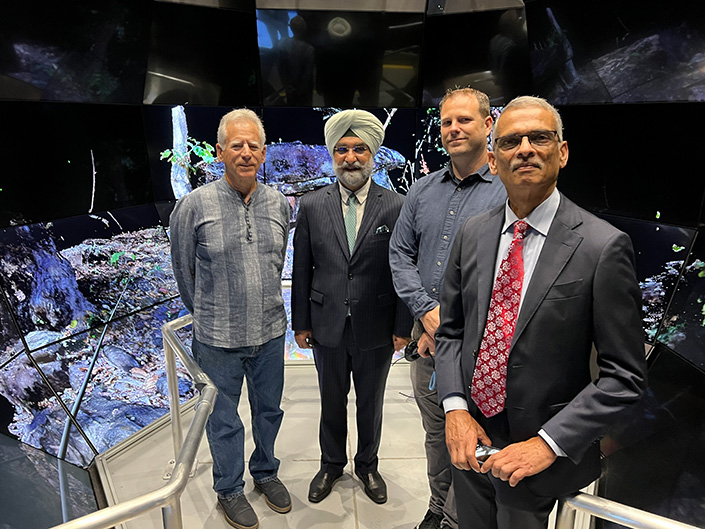

Academic research and the establishment of an American branch of FalconViz finally drew Smith back to San Diego in late 2022. As part of the UC San Diego campus community, he lectures within the Departments of Anthropology and Computer Science and Engineering; runs QI’s SunCAVE, a walk-in virtual reality facility; and mentors students through the Cyber-Archeology Warehouse, or CyberArchWarehouse for short.

Like many others around the world, Smith was barred from traveling to research sites during the pandemic. While the restrictions raised obvious challenges, they also highlighted cyber-archaeology’s strengths. Thanks to the push for digitization, led by Levy, Smith and others in years past, Smith and his colleagues could access virtual copies of their artifacts and make progress even under lockdown. All they lacked was a virtual common space where they could work together.

“I think that’s the next stage of cyber-archaeology: creating an immersive environment in which new ways of research can be done digitally, remotely and, hopefully, in a better way than what we can do physically today,” said Smith.

The CyberArchWarehouse is a step in that direction. Supported by QI’s CCAS and run by Epic Games’ Unreal Engine 5, the warehouse can be imported anywhere. Already, it has produced boundary-pushing projects, such as the recreation of the archaeological site Tel Dan in northern Israel.

The recreation of Tel Dan was a collaborative effort between the Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem, Levy, Smith and three UC San Diego interns in Anthropology, Computer Science and Engineering, and Interdisciplinary Computing and the Arts. Simply by donning a virtual reality headset at QI, visitors can instantly travel to Tel Dan, where they’ll pick up and examine artifacts and learn from an avatar of the late Avraham Biran, who devoted decades to excavating the site.

The team is currently planning to make the tour more accessible via the National Research Platform’s Nautilus cluster, a widespread cyberinfrastructure that spans all 10 campuses of the University of California, as well as other major universities across America. The move would mean students of archaeology anywhere can explore Tel Dan, regardless of the strength of their computer or their access to a high-tech headset.

“Ultimately, I’m looking forward to Neil taking over CCAS entirely,” said Levy. “He will lead new students and faculty into that promised land of the metaverse and cyber-archaeology.”

To learn more about CCAS, visit its website at ccas.ucsd.edu; to learn more about QI, visit qi.ucsd.edu.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.