By:

Published Date

Negating a Revolution

China historian says ‘state consumerism’ evolved as an unofficial policy of the Chinese Communist Party, not anti-capitalism

In 1970s China, Chen Yilin became the proud owner of a regionally made wristwatch, a Yangcheng. His colleagues coveted it, and over time they got their own watches—but these were seen as even more prestigious, as they were made in Shanghai. The luster of Chen’s watch declined, though it still kept time just as well as any other.

Seeing himself as “backward,” Chen decided to buy a Shanghai-brand watch too, but this new brand-awareness didn’t end, and he became the first at his place of work to follow the next trend: Japanese-made Citizen watches that just entered the Chinese market.

He may have lived under a government that loudly criticized the evils and inequalities of capitalism, but Chen was clearly becoming a contemporary consumer: someone who used his purchases to communicate who he was to others.

Historian and Chinese-consumerism expert Karl Gerth. Photo credit: Erik Jepsen, University Communications.

Chen’s story and more lay the foundation for the latest research from historian and Chinese-consumerism expert Karl Gerth, who arrives at a counterintuitive conclusion: the Communist Revolution of 1949 that established the People’s Republic of China and the rulership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) actually accelerated the development and entrenchment of capitalism in the country, instead of ending all forms of it as repeatedly declared.

In short, the CCP negated its own revolution by expanding capitalism, not ending it.

“The spread of consumer desires for industrially produced products, which had already begun to take hold before 1949, helps illustrate how the state both deliberately and inadvertently contributed to building consumerism and negating the Communist Revolution,” said Gerth, the Hwei-Chih and Julia Hsiu Chair in Chinese Studies and a professor of history at the University of California San Diego. “Consumer desires for items such as the ‘Three Great Things’ people wanted—watches, bicycles and sewing machines—was, like capitalism itself, self-expanding and compulsory.”

People began to feel they had to acquire these items no matter what. In some cases, without such things a groom could not find a bride. Gerth explains that while the concept of consumerism would not be meaningful to many poor farmers through much of the 20th century, it contributed to the social and economic changes transforming the entire country.

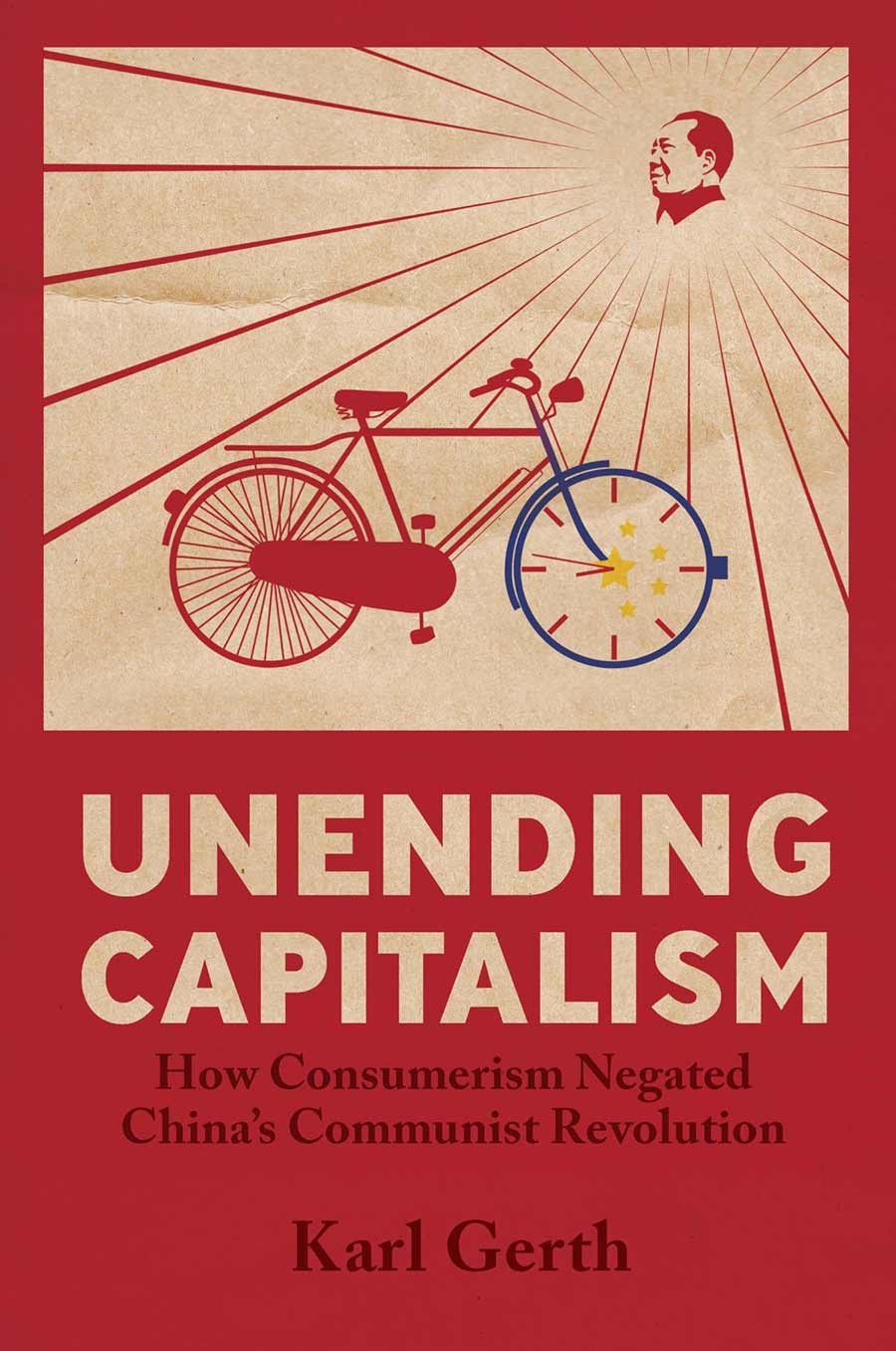

Heavily researched, Gerth’s latest book “Unending Capitalism: How Consumerism Negated China’s Communist Revolution” explains in detail how, under the guise of building socialism, the Chinese Communist Party and its leader Mao Zedong helped accelerate the promotion of the culture of consumption that is critical to capitalism today.

Gerth coins the term “state consumerism,” defined as the wide-ranging efforts within China’s form of state capitalism to manage demand in every respect, from promoting, defining and even spreading consumption while, at the same time, eliminating, discrediting or marginalizing private preferences for the allocation of resources.

“State consumerism is the demand-side correlate of state capitalism. State capitalism is a government having power over the collection and allocation of capital, usually through institutions of central planning and state ownership,” Gerth said. “In the case of the CCP, state consumerism was both the suppression of some consumption and the promotion of other consumption, always with an eye toward helping China industrialize faster. The self-defined socialist state represented not an antithesis to capitalism, but rather a moving point on a spectrum of state-to-private control of industrial capitalism.”

“Unending Capitalism” is the third book from Gerth, director of the Chinese Studies Program in the UC San Diego Institute of Arts and Humanities. His first book was “China Made: Consumer Culture and the Creation of the Nation” published in 2003, followed by “As China Goes, So Goes the World: How Chinese Consumers are Transforming Everything” in 2010.

Gerth said he spent over a decade collecting material for his research on consumerism in China, which, with the publication of “Unending Capitalism” by Cambridge University Press, shows an entire arch of the 20th century to the present.

Using actual histories like Chen’s wristwatch story was important to Gerth. Rather than relying on abstract theories to challenge the entire framework for how we understand communism vs. capitalism during the Cold War, Gerth collected evidence on how Chinese citizens encountered mass-produced goods at the grassroots, learned to desire more and more things, and learned to create and communicate who they thought they were through the things they began to acquire.

Bicycles, film, fashion, travel and even the collection of Mao badges—Gerth explains that the Mao era witnessed the growth of consumer culture through the compulsive participation in what he calls the largest consumer fad in history, the “Mao Badge Phenomenon.” It is, Gerth argues, the desires revealed by everyday, individual lives that expose what is driving history.

“The cases and examples that I use throughout the book are a small fraction of the materials I collected to show how everyday life is better explained as a variety of self-expanding and compulsory capitalism rather than, as the Chinese Communist Party and others argue, a valiant attempt to build a political economy that was the antithesis of capitalism,” he said.

In this new interpretation of the People’s Republic of China, Gerth is suggesting a shift in paradigm regarding how China and other communist countries are defined: definitions that were established during the Cold War as a binary struggle between capitalism and Communism, or “good vs. evil.” While scholarship has added much detail to these histories the dual framing that is perpetuated by states, politicians and the media is seldom challenged even today.

“Since the middle of the 20th century, it’s been pretty easy for politicians and the general public to write off everything bad as ‘socialist’ or ‘communist,’ and associate everything good with ‘free markets, ‘capitalism’ and ‘democracy,’ ” Gerth said, “but rather than being completely opposites, what if we consider the differences associated with ‘socialist’ and ‘capitalist’ countries to be institutional variations of the same underlying priority to expand capital?”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.