How Trauma Gets Under the Skin

Story by:

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

A new study co-authored by Anthony Molina, M.D., professor of medicine and scientific director of the Stein Institute for Research on Aging at the University of California San Diego, has demonstrated that traumatic experiences during early childhood may get "under the skin" later in life, impairing muscle function in people as they age.

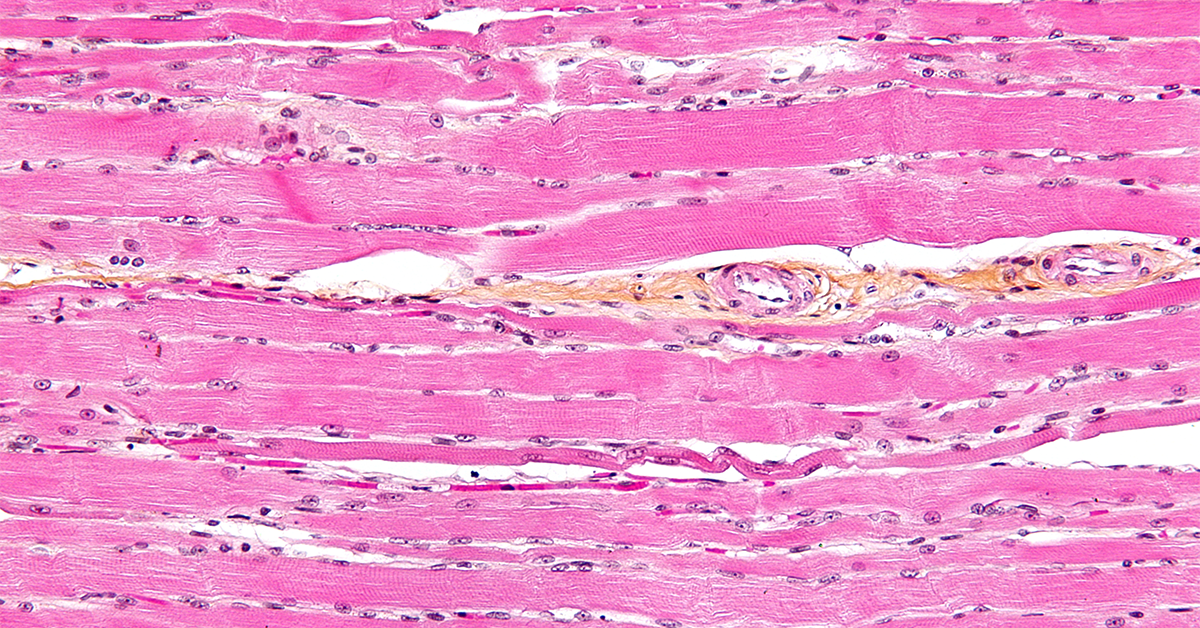

The study, published in Science Advances, examined the function of skeletal muscle of older adults paired with surveys about adverse events they had experienced in childhood. It found that people who experienced greater childhood adversity, reporting one or more adverse events, had poorer muscle metabolism later in life, measured by the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body’s main energy currency.

ATP is produced by structures within cells called mitochondria, which are a major focus of Molina’s research. According to him, these new findings shed light on the mechanisms driving some of his previous observations about mitochondrial function and aging.

"All of my previous studies have been focused on contemporaneous measures: mitochondria and physical function, mitochondria and cognitive function. These studies have shown that these measures are strongly related to our strength, fitness and numerous conditions that impact physical ability. I've also shown that these measures are related to cognitive ability and dementia," Molina said. "But here's the first time we're looking backwards, at what kinds of things that could lead to those differences in mitochondrial function that we know can drive differences in healthy aging outcomes among older adults."

The research team, led by Kate Duchowny, Ph.D. a scientist at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, used muscle tissue samples from people participating in the Study of Muscle, Mobility and Aging, or SOMMA. The SOMMA study includes 879 participants over the age of 70 who donated muscle and fat samples as well as other biospecimens. The participants also were given a variety of questionnaires, physical and cognitive assessments and other tests.

The researchers examined muscle samples to determine two key features of muscular function: how much ATP is produced in muscle cells, and the rate at which cells consume oxygen.

"You can think about oxygen consumption rate as a way to measure the flow of electrons that's going through the electron transport train, and it's these electrons that generate the membrane potential that drives the synthesis of ATP," Molina said. "It's a really precise way of assessing mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity."

They compared these results with questionnaire responses that included information about various early childhood traumas, such as a parent abusing drugs or alcohol, physical or verbal abuse, parental absence, or the loss of a loved one. the team found that about 45 percent of the sample reported experiencing one or more adverse childhood events, and that both men and women who reported adverse childhood events had lower production of ATP. These effects were consistent even after controlling for various other factors that can affect muscle function, such as gender or body mass index, suggesting an underlying relationship between early childhood traumas and mitochondrial function in muscle cells.

"What these results suggest is that these early formative childhood experiences have the ability to get under the skin and influence skeletal muscle mitochondria, which is important because mitochondrial function is related to a host of aging-related outcomes," Duchowny said. "If you have compromised mitochondrial function, that doesn't bode well for a range of health outcomes, including everything from chronic conditions to physical function and disability limitations."

Read the full study: Childhood adverse life events and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function | Science Advances

Additional co-authors of the study include: David J. Marcinek at University of Washington, Theresa Mau, L. Grisell Diaz-Ramierz, Li-Yung Lui, Peggy M. Cawthon and Steven R. Cummings at University of California San Francisco, Frederico G. S. Toledo and Anne B. Newman at University of Pittsburgh, Russell T. Hepple at University of Florida, Philip A. Kramer and Stephen B. Kritchevsky at Wake Forest University and Paul M. Coen at AdventHealth.

Funding: The study was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (grants AG059416, P30AG024827, P30AG021332, UL1 0TR001420, R00AG066846).

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing interests.

This story was adapted from a press release issued by the University of Michigan

"All of my previous studies have been focused on contemporaneous measures: mitochondria and physical function, mitochondria and cognitive function. These studies have shown that these measures are strongly related to our strength, fitness and numerous conditions that impact physical ability. I've also shown that these measures are related to cognitive ability and dementia. But here's the first time we're looking backwards, at what kinds of things that could lead to those differences in mitochondrial function that we know can drive differences in healthy aging outcomes among older adults."

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.