Rising Temperatures: How Can SoCal Survive the Heat Crisis?

NSF-funded Southern California Extreme Heat Research Hub brings together interdisciplinary team of UC San Diego scientists to study extreme heat impacts, mitigation strategies

Story by:

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

It’s shaping up to be another cruel summer for the nearly 24 million people who call Southern California home. After the 2023 season claimed the title of Earth’s hottest on record, the summer of 2024 is well on its way to surpassing it, with temperatures across the globe becoming more extreme and life-threatening heat waves increasing in both frequency and duration. The region’s highly populated coastal areas are bracing for more scorching summers in the years ahead, and the stakes have—quite literally—never been higher.

At UC San Diego’s world-renowned Scripps Institution of Oceanography, this sense of urgency propels the work of scientists from a broad range of disciplines who are studying the complex atmosphere, land and ocean processes that affect extreme temperatures along the Southern California coast.

Their work explores the impacts of heat on human health and investigates how sustainable use of green space can help mitigate those impacts. And that’s not all: they’re taking their real-world research beyond the lab, spearheading climate science education efforts for K-12 students and engaging local community partners in developing innovative solutions to this escalating crisis.

Established in 2022 through funding from the National Science Foundation’s Coastlines and People (CoPe) research initiative, the Southern California Extreme Heat Research Hub—better known as the SoCal Heat Hub— brings together teams from fields like climatology, epidemiology and public policy that wouldn’t ordinarily work collaboratively, explains coastal oceanographer Mark Merrifield, the hub’s principal investigator.

“The breadth of research being done across UC San Diego means that we can pull a whole team together largely from our own bench,” says Merrifield, who also serves as the director of UC San Diego’s Center for Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation. “Together, we’re working to enable a safer, more prepared San Diego and Southern California, to avoid tragic outcomes and to motivate efforts to reduce carbon emissions so that we avoid the worst scenarios going forward.”

Through an innovative, multidisciplinary approach to these complex problems, the hub’s research teams—now two years into a five-year project—are well on their way to generating impactful, data-driven solutions for long-term climate resilience in the face of extreme heat not only in Southern California, but in other coastal regions around the globe.

Understanding the drivers of heat waves

How does proximity to the ocean influence heat waves on land, and what role does climate change play in this highly complex dynamic? What types of predictive models might help people in coastal areas deal with the negative impacts of heat waves?

Within the SoCal Heat Hub, Kristen Guirguis, Rachel Clemesha, Alexander (Sasha) Gershunov and Ph.D. student Alexander Weyant are working together to answer these questions through the study of atmospheric, land and ocean dynamics. Guirguis’ work centers on how weather patterns can predict heat events in specific areas, while Clemesha’s focuses on coastal low clouds—a common sight in San Diego—and how they’re affected by climate change.

A forthcoming paper—one of the first to come out of the Heat Hub project—describes how extreme heat on land in Southern California is tied to extreme heat in the ocean. Lead author Maren Hale, who serves as the SoCal Heat Hub project manager, says that the team found that the number of extreme temperature days in the coastal zone varies with ocean conditions—notably during recent marine heat waves.

Gershunov, a meteorologist and climatologist who has studied extreme weather events for decades, says that his work on heat waves gained momentum following the state’s unprecedented 2006 heat wave, which resulted in hundreds of fatalities and marked a turning point in the region’s public awareness of the growing dangers posed by a warming climate.

Since then, Gershunov’s research has revealed that this trend continues, with heat waves becoming more humid and more dangerous in the region, particularly in coastal areas where air conditioning is less prevalent. The team’s research also indicates that marine heat waves—boosted by the warming of the ocean—exacerbate nighttime expressions of heat waves on land and intensify their overall impact by adding humidity to the heat.

Through an analysis of California statewide temperature trends, the team’s work has revealed that nighttime temperatures, particularly during heat waves, are rising faster than daytime temperatures. These findings highlight a major gap in heat-related policy, as to date nearly all local-level mitigation efforts and actions—such as the operation of cooling centers—are focused on heat solely as a daytime issue.

Not only are there many different “flavors” of heat waves that pose problems both day and night in Southern California—but they’re also occurring year round, Gershunov says. He compares climate change to a “steroid”—one that amplifies weather extremes such as heat waves.

“In this part of the world, we actually have fall, winter and spring heat waves that are driven by Santa Ana winds that send people to the hospital because of heat even in the winter,” says Gershunov. “The same weather patterns that drive coastal heat waves in the fall, winter and spring also can spread catastrophic wildfires."

Collaborating with public health experts such as epidemiologists to connect the dots between weather patterns and hospitalizations, for example, has been crucial to this work. According to Gershunov, the level of communication and collaboration between these two fields within the SoCal Heat Hub and Scripps Institution of Oceanography is unique and unprecedented.

“I don’t think there’s any other place where climate scientists and epidemiologists collaborate as closely as we do here,” says Gershunov. “We’re hoping to provide valuable information for health professionals and other decision-makers to make more informed decisions that will actually have positive impacts, including saving people’s lives during these extreme heat waves that we are experiencing—and unprecedented heat waves that we have yet to experience."

"I don’t think there’s any other place where climate scientists and epidemiologists collaborate as closely as we do here."

Exploring the impacts

Often referred to as a “silent killer,” extreme heat claims more lives and sends more people to the hospital than hurricanes, floods or any other type of weather event in the United States. As heat waves become more intense and prolonged, research at the intersection of public health and extreme heat is increasingly critical—and lives depend on it.

SoCal Heat Hub efforts led by environmental epidemiologist Tarik Benmarhnia delve into the physiological effects and societal challenges posed by rising temperatures. Much of the team’s work in this space focuses on the disproportionate impact of heat waves on vulnerable populations such as older adults, unhoused individuals and those with chronic health conditions—all of whom face compounded risks during extreme heat events.

It's widely understood that heat waves can lead to heat stroke, heat exhaustion and dehydration, but Benmarhnia explains that the impact is disproportionately felt by those already at risk, including individuals with preexisting health conditions—such as diabetes, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—that are exacerbated by heat and the body’s attempts to thermoregulate in response.

The SoCal Heat Hub’s research goes beyond general health impacts to understand the specific vulnerabilities of certain populations and how urban environments and socioeconomic factors determine who faces the brunt of these impacts. Benmarhnia’s team identifies medical conditions—such as pregnancy, diabetes or certain mental illnesses—that can become problematic during heat waves and investigates why these conditions make individuals more susceptible. This research has significant implications for preparedness in hospital emergency departments, which must be ready to handle the influx of patients during extreme heat events.

Working closely with Gershunov and his team of researchers, Benmarhnia also dedicates a significant portion of his work to evaluating the effectiveness of early warning systems for heat waves and improving heat action plans tailored to specific cities, counties or communities. These plans, which can include the opening of cooling centers and implementation of other interventions, aim to mitigate the health impacts of extreme heat and build resilience in vulnerable communities.

Through their work, the team is also exploring the synergistic effects of heat and other environmental factors such as wildfire smoke and ozone.

Developing mitigation strategies

The concept of urban greening—incorporating green spaces into urban environments to help cool down densely populated areas—sounds simple enough. Plants and trees provide shade, which reduces surface temperatures and provides a cooling effect. But the SoCal Heat Hub ecohydrology team, led by Morgan Levy, an environmental scientist with a joint appointment between Scripps Institution of Oceanography and UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy, are finding that in implementation, it’s a lot more complex than that.

They’re working to better understand the interactions between vegetation, water and temperature to develop more effective strategies for heat adaptation, particularly in “urban heat islands”—a term for the amplified heat effects in built environments that largely consist of concrete buildings, asphalt parking lots and dark rooftops.

“We know that trees make places cooler,” she notes. “But in an environment where we’re adapting to heat, we need to understand how specific quantities and types of vegetation can generate meaningful cooling impacts, particularly from a health perspective.”

Armed with data on plants and heat in Southern California and working in collaboration with community partners across the region such as Tree San Diego, Levy’s group is exploring what resources are needed to support trees in urban environments and the vital role that water supplies and water infrastructure play in maintaining and sustaining those cooling effects.

In an arid environment like Southern California, where water supplies are already limited, increasing vegetation to reduce heat means increasing water demand, Levy explains, adding that the Heat Hub’s goal is to identify sustainable greening strategies that can provide significant cooling benefits without straining water supplies.

As the interdisciplinary collaborations within the SoCal Heat Hub progress, Levy and her team aim to produce actionable urban planning designs that outline optimal greening plans for temperature reduction. She believes that San Diego is the ideal location to explore this particular topic.

“We have a number of large cities just in Southern California alone that are on coasts, and coasts provide a perfect scientific environment for experimentation and understanding because of the physical variability, socioeconomic variability and diversity,” Levy says. “All of these create a really good research environment."

Educating the public

The research being conducted within the SoCal Heat Hub may be groundbreaking—but the true heart of its work is found outside of the lab, where Heat Hub scientists are partnering with school districts and local organizations to increase public awareness of the impacts of extreme heat.

Just last month, Gershunov and Weyant installed a weather station in San Diego’s scenic Balboa Park on the grounds of the WorldBeat Cultural Center—a nonprofit, multi-cultural arts organization dedicated to preserving the African Diaspora and Indigenous cultures of the world. The solar-powered station records pressure, temperature, humidity, wind, precipitation and solar radiation, transmitting the collected data to a console located inside the building and to a server where the data is archived and made available to the public. The center’s staff can then use that data to inform their gardening activities, event planning, educational activities and future urban greening projects.

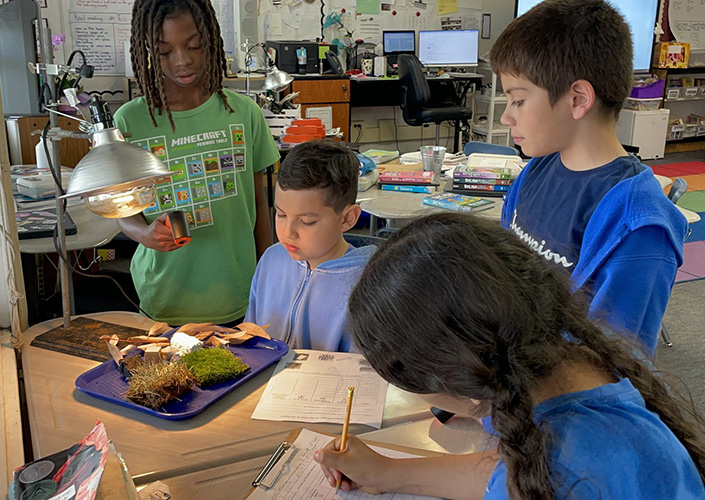

This station is just one of several that the Heat Hub team is installing throughout San Diego—most of which are at local middle schools, and predominantly in underserved communities that face disproportionate impacts of extreme heat. In these schools, Heat Hub scientists are collaborating with teachers to integrate weather into their science curriculum, and even visiting sixth-grade classrooms to teach concepts in physics and data visualization based on the measurements taken on their own campuses.

This summer, the Heat Hub team will install a weather station at the UC San Diego Center on Global Justice’s EarthLab, a climate action park designed for experiential outdoor education in San Diego’s underserved Encanto community and located next to Millennial Tech Middle School.

These connections within the local community have been made possible through a partnership with the San Diego Regional Climate Collaborative, a program of the University of San Diego, which takes an equity-first approach to climate adaptation and resilience strategies.

For Nan Renner, senior director of strategic partnerships at Birch Aquarium at Scripps and co-principal investigator for K-12 education in the SoCal Heat Hub, community engagement opportunities like these are key to ensuring a better future for our planet.

“We see students and teachers as vital community advocates,” says Renner. “The climate movement also needs to bring in fun and joy. Our ability to respond to climate change depends entirely on the community, so that’s the approach we’re taking with K-12 education and with our community partners."

Renner and her team have worked with San Diego Unified School District to develop a fifth-grade Cooler Communities curriculum based on Heat Hub science, which invites students to explore weather phenomena, Earth systems relationships and more. From the outset of this collaboration with local science educators and entities such as UC San Diego CREATE, a community-facing research-practice-partnership center committed to supporting equitable educational opportunities for San Diego’s students, Renner and her team uncovered a tangible need for this type of program.

“We have found great demand for climate science education and high interest in heat waves, urban heat islands and extreme heat events, and what they mean for our communities—particularly vulnerable communities, which are especially affected by extreme heat,” Renner says, explaining that most school sites in San Diego County can be considered urban heat islands and will become unsafe environments for children in a warming climate. “We want to test and improve upon our strategies to support student voices in advocating for greening their school grounds,” she adds.

The Heat Hub team has also supported events like community round tables that bring together partner organizations, as well as the Climate Champions Design Summit which unites educators and scientists to explore heat phenomena together. Central to these teacher training events are the use of satellite data maps produced by Maren Hale and Laney Wicker, a Ph.D. student in Levy’s lab. These visualizations allow students to track patterns and explain causal relationships in Earth systems and make climate science education more accessible in the classroom setting.

Through broadening student participation in STEM and empowering individuals from hard-hit communities to participate in building solutions, researchers in the SoCal Heat Hub see a beacon of hope for the future as the region continues to face the mounting challenges of extreme heat. This hope motivates them to continue pushing the boundaries of climate science in their work.

“I think we’ve only just gotten started,” says Merrifield.

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.