Hot Cars Can Hit Life-Threatening Levels in Approximately One Hour

Interior temperatures can rise to 116 degrees Fahrenheit, potentially causing fatal injuries to children trapped inside

Published Date

By:

- Michelle Brubaker

Share This:

Article Content

Six children have died from being left in hot cars in the United States so far this year, according to the web site noheatstroke.org, a program supported by the National Safety Council. That number will rise with looming summer temperatures. On average, 37 children in the U.S. die each year due to complications of hyperthermia — when the body warms to above 104 degrees Fahrenheit and cannot cool down — after being trapped in overheated, parked cars.

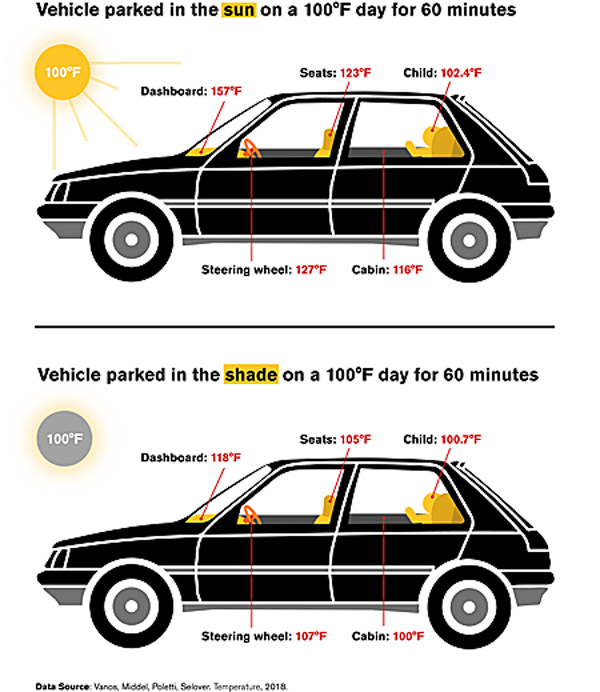

Researchers from University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Arizona State University found that if a car is parked in the sun on a summer day, the interior temperature can reach 116 degrees F. and the dashboard may exceed 165 degrees F. in approximately one hour — the time it can take for a young child trapped in a car to suffer fatal injuries.

Infograph courtesy of Arizona State University

The study, published May 24 in Temperature, compared how different types of cars warm up on hot days when exposed to different amounts of shade and sunlight over different periods of time. More importantly, the researchers also took into account how these temperature differences would affect the body of a hypothetical two-year-old child left in a vehicle on a hot day.

“Young children are vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat with increased emergency department visits found during heat waves. Internal injuries can begin at temperatures below 104 degrees,” said first author Jennifer Vanos, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. “As compared to adults, children have a quicker rise in core temperature and a lower efficiency at cooling.”

Researchers used six vehicles for the study: two identical silver mid-size sedans, two identical silver economy cars and two identical silver minivans. During three summer days in Tempe, Arizona with temperatures in the 100’s, researchers moved the cars from sunlight to full shade (under solar panels) for different periods of time.

“We’ve all gone back to our cars on hot days and have been barely able to touch the steering wheel,” said Nancy Selover, PhD, study co-author, climatologist and research professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University. “Imagine what that would be like to a child trapped in a car seat on a hot day, either in the sun or shade.”

The researchers found that, for vehicles parked in the sun during a simulated shopping trip, the average temperature inside the vehicles hit 116 degrees F., dashboards 157 degrees F., steering wheels 127 degrees F. and seats 123 degrees F. in one hour. For vehicles parked in the shade, interior car temperatures were closer to 100 degrees F., dash boards averaged 118 degrees F., steering wheels 107 degrees F. and seats 105 degrees F. after one hour.

“We found that a child trapped in a car under the study’s conditions could reach a body temperature of 104 degrees F. in about an hour if a car is parked in the sun, and just under two hours if the car is parked in the shade,” said Vanos. “This body temperature could be fatal to infants and children — and those who survive may sustain permanent neurological damage.”

More than 50 percent of cases of a child dying in a hot car involve a parent or caregiver who forgot the child in the car.

“Children and infants are unable to control the environment, communicate well and often fall asleep during car rides,” said Vanos. “Even in our technologically advanced world, human error results in children dying every year in the U.S. from being left in hot vehicles. All of which are 100 percent preventable.”

The different types of vehicles tested in the study warmed up at different rates, with the economy car warming at the fastest rate and the minivan the slowest due to relative air volumes. However, when addressing the overall heat gain from temperature, radiation and other factors, a person’s age, weight, existing health problems and other factors, including clothing, will affect how and when heat becomes deadly.

Vanos and the research team hope these findings will result in new behavioral and technological interventions that will save the lives of the most vulnerable car passengers.

Co-authors include: Ariane Middel, Temple University; and Michelle N. Poletti, Florida International University.

This research was funded, in part, by the National Science Foundation (DEB-1026865), Central Arizona-Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research, Arizona State University LightWorks, and Strategic Solar Energy.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.