Experiment in Progress

UC San Diego music remains a laboratory for the arts.

Story by:

Media contact:

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

This story was published in the Spring 2023 issue of UC San Diego Magazine.

Lei Liang approaches music from the widest possible view. He says that on a certain level, almost anything can be music. One day, he brought the sounds of Arctic ice and beluga whales to class and asked his students to listen if they wanted.

“I played it and nobody left,” says Liang, who serves as the Chancellor’s Distinguished Professor of Music at UC San Diego. “In fact, it was the most beautiful, deep listening experience that I have witnessed in class. It’s not that they loved the sound, but it evoked something very deep in them. They recognized the sound without ever having set their foot in the Arctic.”

That’s exactly what the Department of Music wants its students and faculty to do — not just to make music but also to consider what music is, why it matters and how

it will move us into the future. And it has been that way from the start.

“The early campus leaders saw the importance of the arts and had this radical idea of art laboratories,” says Rand Steiger, distinguished professor and Conrad Prebys presidential chair. “They wanted to start departments that were about creating the future of the arts.”

That meant cutting-edge visual artists were sought out to start the Department of Visual Arts. Progressive playwrights and directors were called to start the Department of Theater and Dance. And young composers were recruited to start the music department.

Steiger has seen it all firsthand. He has been a member of the music faculty at UC San Diego since 1987, and one thing has not changed: The department has always been forward-looking and experimental, defined by the generations of faculty and students who have walked through its halls.

“I love the way the department evolves,” says Steiger. “The energy and ideas from new faculty are inspirational and insightful.”

As one of the newest hires, King Britt is re-imagining the Department of Music for yet another generation. He is a veteran producer, composer and performer of electronic music. He created the lecture course Blacktronika: Afrofuturism in Electronic Music because no one was talking about this genre with any authority but he is living it.

Britt has released more than 100 albums, records and remixes, in addition to owning a record label. He has remixed everyone from Meredith Monk and Calvin Harris to Solange and John Legend. He says his love of music came from his parents, who were avid collectors of records: avant-garde jazz for his mother, and strictly funk for his father. When he was a child, his mother took him to jazz legend Sun Ra’s rehearsals; the musicians reminded him of Black superheroes. He distinctly remembers Herbie Hancock’s album Sextant with its cover featuring African aliens dancing in space with Saturn in the background. These early musical influences helped lay the groundwork for his obsession with how records were made.

“For Blacktronika to be a part of the curriculum here at UC San Diego...shows how on the cutting edge we really are.”

Britt’s own early music-making was trial and error.

“We acquired a lot of used equipment, and when you get things used, there’s usually no manual — this was before the internet — and so you just start turning knobs and figuring things out on your own,” he says.

Britt still utilizes that method in his teaching; he wants his students to understand the relationship between experimentation and new ideas in music. For his computer music production class, he finds that a hybrid approach works best. The class meets twice a week. One day is on Zoom: Britt presents the techniques and provides students with a stereo recording of the lecture. They spend the second day in the studio and apply the techniques they have learned, live.

Blacktronika, however, which honors the people of color who have pioneered groundbreaking genres within the electronic music landscape, was created as an online course. Britt plans to keep it that way because dance music, he says, sounds better through headphones than it ever would in a cavernous lecture hall.

The course has 300 students and special guests every week, including Questlove and George Clinton among many other icons.

“For Blacktronika to be a part of the curriculum here at UC San Diego is showing that we’re decolonizing the pedagogy that has existed, especially in the area of electronic music,” Britt says. “Musically as well as culturally, it shows how on the cutting edge we really are.”

Amy Cimini is also driven to challenge he way music education is conceived and taught. Cimini comes from a more traditional music background: She studied viola performance at Oberlin Conservatory and later earned a PhD in historical musicology. But she also felt like something was missing.

“As a musician, you’re not taught music research,” she says. “You’re not taught to participate or intervene in the production of knowledge about music and culture.”

Cimini emphasizes that the UC San Diego Department of Music challenges that educational approach by doing away with more traditional music history requirements, replacing them with a hands-on research-driven course centered on social and political questions. Students are guided through the development of an original research project.

“It’s an amazing chance for our music majors to show that research questions are integral to all aspects of the creative process. There’s a tendency to separate them out: creativity happens here and research happens over there. But they are all tangled up with each other.”

As such, Cimini sees her work as decidedly interdisciplinary.

“Gender gets coded into these structures and is repeated, naturalized and becomes part of how and what you listen to."

Today, Cimini explores music through the lens of gender. She’s interested in how ideas of gender get attached to different types of sound, different melodies or different musical structures.

“Gender gets coded into these structures and is repeated, naturalized and becomes part of how and what you listen to. These are institutional hierarchies that have been made, circulated and perpetuated,” says Cimini. She wants to break these barriers down.

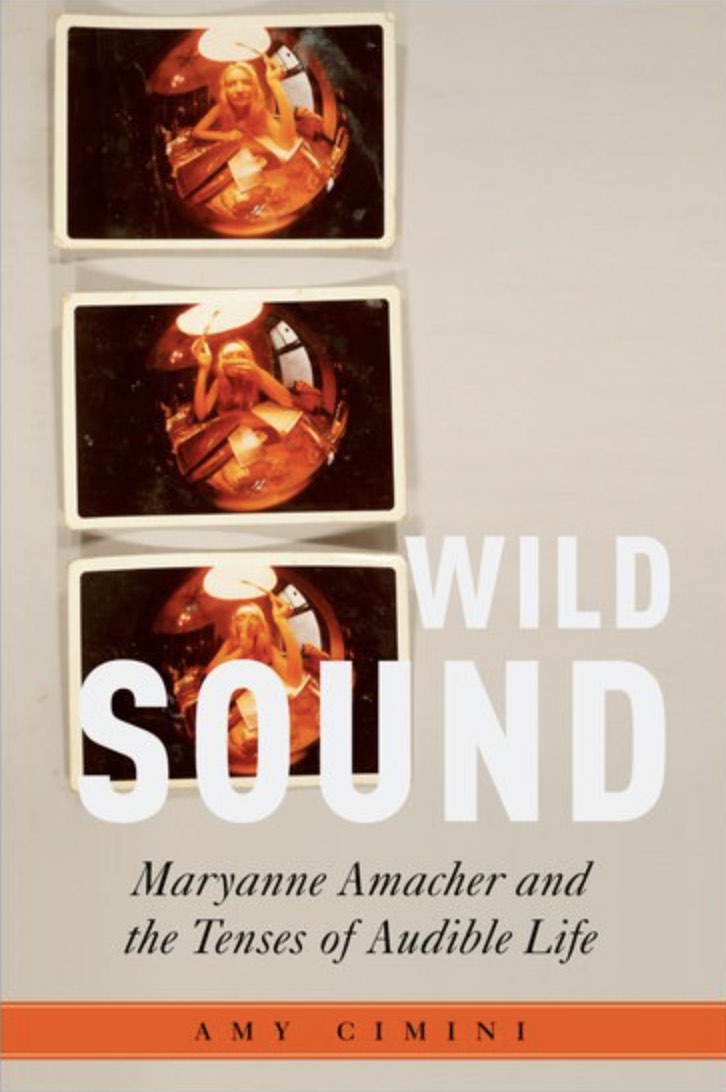

Cimini’s book Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life explores the work of the pioneering electronic music composer while also examining how feminized workers have engaged with sound and electronics. For instance, in her book, she sees telephone operators, an occupation primarily held by women, at the forefront of new communication and sound technologies.

“I’m trying to break apart some of those traditional divisions of whose work and sound is considered valuable,” she says. “We encounter so many other forms of creativity and worldmaking in sound and technology when we take a more expanded view.”

For Lei Liang, the expanded view comes from learning to listen — to anything and everything.

“Listening is powerful, but it’s often underestimated in the context of teaching,” he says. “If we unleash the potential of listening, we can learn more about the world around us, from the ocean to earth.”

Like Cimini, Liang learned to play an instrument at a young age. He started playing piano at age 4 but became bored by the pieces he was given to practice at the Musical Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Arts in Beijing. By age 6, he was composing his own music.

He felt constricted by the conservatory setting and eventually broke free from it. From 2013 to 2016, Liang was recruited to serve as composer-in-residence at the Qualcomm Institute at UC San Diego, a division of Calit2. There, he created multimedia work to preserve and re-imagine cultural heritage by combining scientific research and advanced technology. He returned to the institute in 2018 as its inaugural research artist-in-residence. Much of his work involves the utilization of scientific data from one of the most inaccessible places in the world: the Arctic Ocean.

“Listening is powerful, but it’s often under estimated in the context of teaching. If we unleash the potential of listening, we can learn more about the world around us, from the ocean to earth.”

“We’re missing this incredible music that’s being made in the ocean,” says Liang.

He worked with John Hildebrand and Josh Jones, oceanographers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who have deployed hydrophones hundreds of meters deep below the sea surface to record the sounds of the ocean.

Liang gathered data on whales, seals and even ice — some sounds that the human ear cannot perceive. But Liang is resampling the sounds and bringing them into a human range with a project called Inaudible Ocean, which was made possible by interdisciplinary collaboration of the artists and scientists who come together at UC San Diego.

“We are all part of this great university, a place of great learning,” says Liang. “Artists, musicians, data scientists, engineers and oceanographers can work together to share new modes of thinking, new ways of learning and new tools to enhance learning.”

Liang sees the artist as an intermediary, helping to transform data, such as the thousands of hours of ocean sound recordings, into an experience that can be shared with a wider audience.

And that’s what the arts, and science, are all about. These subjects open our eyes (and ears) to new possibilities, ideas and experiences. With its roots deeply embedded in experimentation, the Department of Music is doing its part to help the university live up to the ambitious laboratory of arts that its founders had intended all along. No doubt it will continue to grow, evolve and usher thought-provoking new music into our collective consciousness.

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.