Calling All Shark Lovers

Scripps Oceanography’s Brendan Talwar is competing in "All the Sharks," a new Netflix series airing July 4

Published Date

Article Content

As summer kicks into high gear on the Fourth of July, Netflix is releasing a new series highlighting the beauty, importance and diversity of shark species around the globe.

Set to be released on July 4, All the Sharks is the first series where shark lovers travel the world to photograph as many sharks as possible. Four teams compete against one another in hopes of winning a $50,000 prize for a marine charity of their choice. From the Caribbean to the Pacific, these contestants will come face to face with all kinds of toothy friends.

Brendan Talwar, a marine fisheries ecologist and postdoctoral scholar at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, is one of the contestants on the show. Talwar is a member of both the IUCN Shark Specialist Group and the lab of researcher Brice Semmens at Scripps, where his research focuses on the conservation and management of threatened species, sustainable fishing and healthy seafood. He is partnered with marine biologist Chris Malinowski to compete in All the Sharks, working together to explore the most spectacular shark habitats.

Interested in meeting Brendan? He’ll be one of the featured scientists at Birch Aquarium’s Shark Summer pop-up event from 5-8 p.m. on July 10! Follow along with the educational materials that Talwar and Malinowski will be posting on Instagram (@Shark_Docs) and YouTube throughout their journey.

We caught up with Talwar to learn more about his shark research and involvement in this ‘fintastic’ new series.

Tell us about All the Sharks. Why were you interested in participating?

I was recently reminded of a moment I had in The Bahamas a few years ago. I was out on the boat with a group of undergraduates from Monmouth University during their Tropical Island Ecology field course, and we were cruising Exuma Sound, a deepwater basin, to scan for whales breaking the surface just as we did in years past. Some years, everyone falls asleep, and nothing reveals itself from the deep blue. Other years, the ocean will bless you with a gift — this time in the form of floating debris. Knowing that life in the open ocean aggregates around structure, we got closer to investigate, and I hopped in. I was welcomed by swarms of flashy bar jacks and other small fishes and a very excited school of juvenile silky sharks — my favorite species at their most curious life stage. I squealed through my snorkel as they turned to swim towards me in greeting — bold as ever — and hopped back on the boat to tell the students to kit up. Over the next hour, the students joined me in groups of three to spend a few minutes with the little sharks in blue water watching light rays play across their smooth, shiny skin. This is how I see sharks – beautiful, exciting and diverse ambassadors for our oceans. And I love sharing that perspective with others.

So, when I was asked to be on All the Sharks to celebrate shark and ray biodiversity by entering a competition where each encounter is a “win,” it made for an easy decision. I was intrigued by the opportunity to dive into the world’s most incredible marine ecosystems, spend months with one of my closest friends, and maybe bring home $50,000 for two nonprofits close to my heart — the Reef Environmental Education Foundation and Ocean First Institute. In joining the production, I hoped to be part of a team that reinvents “shark-TV” by dropping the manufactured drama typical of most sharky programs. All the Sharks makes the case for our oceans being the greatest playgrounds on Earth — places where the most fantastic encounters are just around the corner and where sharks and rays are abundant, valuable parts of healthy and diverse marine ecosystems. The most memorable moments of my life have been underwater, shared with friends and students, and All the Sharks will allow us to share some of the most fantastic moments I’ve ever had with viewers across the globe.

What sort of shark research do you focus on?

I am a marine fisheries ecologist, so I’m broadly interested in the intersection between fishing and the lives of marine animals. Initially I became interested in sharks not because I loved them more than any other taxonomic group, but because they are caught and killed so frequently by fishing fleets. Tens of millions of sharks are killed every year, sometimes for meat and fins and sometimes just because they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. This happens so frequently that many shark populations have declined dramatically in recent decades, and many shark species are now of conservation concern. The threats that they face got me hooked on a career in research, education and policy with the goal of supporting sustainable fishing, which would really be a win-win for people and the animals.

When I do “shark research,” I’m actually attempting to do the research that is required to better manage shark populations; yet, in a sense, I’m also studying the animals in order to better manage people. Answering even basic questions about shark biology, such as, how long do they live? Or how many years does it take to reach sexual maturity? — can inform conservation assessments and lead to improved fishery management, ultimately improving shark population status. For example, we recently completed a study on the spatial population structure of the silky shark, which is caught in tuna fisheries by the hundreds of thousands every year. After interpreting vast quantities of data from the Eastern Pacific Ocean, we proposed a new way to conduct population assessments for this species, and the results of those assessments may lead to improved management.

I want to emphasize that there are many, many steps in between learning something about a species and having a direct management outcome. In marine fisheries ecology, it takes chipping away at big questions over many years to approach fishery sustainability, and, in true form, our study relied on years of data collected by many scientists across the region.

There is so much that we don’t know about sharks and their relatives, yet we’re catching and killing many species too quickly. That’s why shark research isn’t just important — it is also urgent.

I understand you are also doing work on the DDT issue offshore Southern California. Can you tell us about that research?

Yes, absolutely! Once a widely used pesticide, DDT is considered a “legacy pollutant,” because it was released into the environment decades ago, yet it and its breakdown products, collectively referred to as DDT+, still remain in the environment due to very slow degradation. You may be familiar with DDT from Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring, which rang the warning bells about the effects of industry on the environment at a time when rivers literally caught fire due to nonexistent environmental protections.

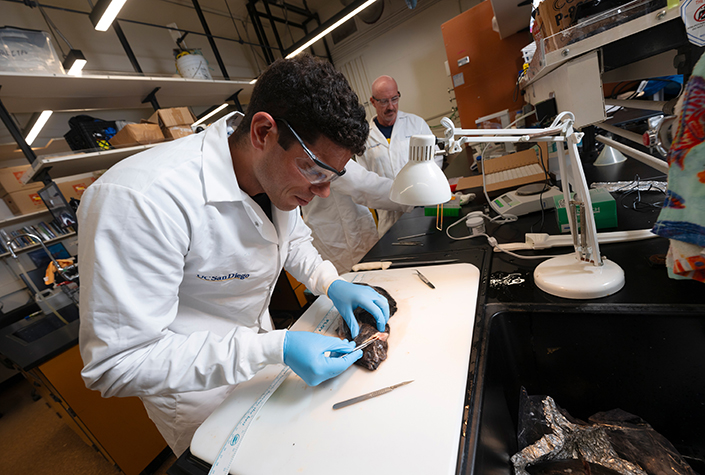

ecades after DDT was banned and federal environmental agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency, were established, scientists rediscovered barrels of industrial waste, including waste from DDT manufacturing, deep below the ocean’s surface a short distance from Los Angeles. Because DDT+ and other toxicants accumulate in the tissue of things we like to eat, like big deepwater fishes, there was a need to study the prevalence of DDT+ in fishes of the Southern California Bight, particularly those that are popular recreational and commercial targets.

Our lab, led by Dr. Brice Semmens and including my colleagues Dr. Lily McGill and Toni Sleugh, among others, is doing the research that can, at its most fundamental level, help us better understand how DDT+ moves through complex marine food webs and determine where it eventually ends up. For example, in which types of fishes, like those that live near the seafloor or those that live near the sea surface, does it tend to accumulate most, and why? At the most applied level, this research will provide data for policymakers to set seafood consumption guidelines for species that often end up on our plates. By analyzing each individual fish in fine detail, we might enable those guidelines to be more precise than a simple “safe to eat” label for a given species in a broad geographic area and instead provide guidance based on a combination of information that anyone can collect — capture location, fish size and species, for example. You wouldn’t expect equal amounts of DDT+ to be in one fish that has lived for only six months and another that has lived for decades.

This is new and important research. Many of the species we’re studying haven’t been assessed before, and some may serve as ecological indicators of deep-sea contamination or potential vectors of exposure to humans.

What do you hope viewers take away from All the Sharks?

Great question. When I began to prepare for the show, I scratched a few talking points onto a sheet of paper that traveled with me to every location. These are the messages I wanted to convey throughout:

- Sharks and their relatives are incredibly diverse! There are over 500 species of shark and over 600 species of ray. Most shark species live in the deep ocean and are less than 1 meter (~3 feet) long — they are not the stereotypical giants of your nightmares.

- Sharks fill diverse roles — both in ecosystems and for humans — and can be ecologically, economically and culturally important.

- Overfishing is the primary threat to sharks and rays. Tens of millions of sharks are killed every year, and global shark mortality has increased in the last decade, particularly in coastal regions. Although the fin trade is significant and drives some species towards a high risk of extinction, the meat trade is of higher economic value worldwide.

- More ray species are threatened with extinction than shark species.

- A live shark is worth more than a dead one. Often, in places where sharks and rays are still abundant, ecotourists will pay top dollar to see thriving marine ecosystems that include these predators.

- Around 80% of wilderness has been transformed for human use, leaving few wild places on Earth. Together, we should protect those that remain.

If viewers — particularly folks who wouldn’t typically watch a nature documentary or swim in the ocean – walk away with a deeper appreciation for sharks, rays and our marine ecosystems, then we’ve succeeded. And I’m excited to hear that the show makes for a fun and exciting adventure for the whole family. The teacher in me couldn’t be happier.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.