Alcohol Also Damages the Liver by Allowing Bacteria to Infiltrate

Natural gut antibiotics diminished by alcohol leave mice more prone to bacterial growth in the liver, exacerbating alcohol-induced liver disease

Published Date

By:

- Heather Buschman, PhD

Share This:

Article Content

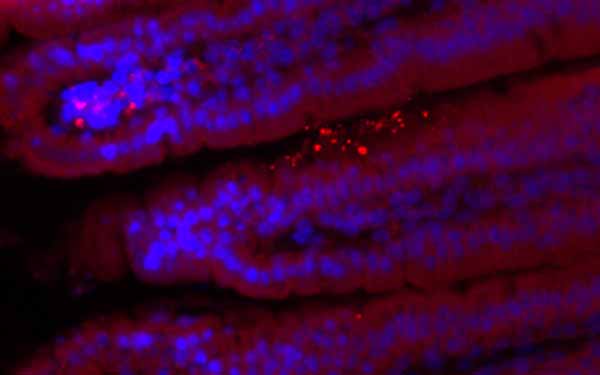

Mice lacking REG3G had more bacteria (bright spots) in their gut linings.

Alcohol itself can directly damage liver cells. Now researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report evidence that alcohol is also harmful to the liver for a second reason — it allows gut bacteria to migrate to the liver, promoting alcohol-induced liver disease. The study, conducted in mice and in laboratory samples, is published February 10 in Cell Host & Microbe.

“Alcohol appears to impair the body’s ability to keep microbes in check,” said senior author Bernd Schnabl, MD, associate professor of gastroenterology at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “When those barriers breakdown, bacteria that don’t normally colonize the liver end up there, and now we’ve found that this bacterial migration promotes alcohol liver disease. Strategies to restore the body’s defenses might help us treat the disease.”

Schnabl and team previously found that chronic alcohol consumption is associated with lower intestinal levels of REG3 lectins, which are naturally occurring antimicrobials.

In their current study, the researchers discovered that REG3G deficiency promotes progression of alcohol-induced liver disease. Mice engineered to lack REG3G and fed alcohol for eight weeks were more susceptible to bacterial migration from the gut to the liver than normal mice who received the same amount of alcohol. REG3G-deficient mice also developed more severe alcoholic liver disease than normal mice.

To find methods for stemming the tide of liver-damaging microbes, Schnabl and team tried experimentally bumping up copies of the REG3G gene in intestinal lining cells grown in the lab. They found that more REG3G reduced bacterial growth. Likewise, restoring REG3G in mice protected them from alcohol-induced fatty liver disease, a condition that precedes end-stage cirrhosis.

Human small intestine samples supported some of the team’s finding in mice. Not only do patients with alcohol dependency have lower levels of REG3G than healthy people, they also have more bacteria growing there.

Liver cirrhosis, or end-stage liver disease, is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, and approximately half of these deaths are related to alcohol consumption.

Study co-authors include Lirui Wang, Cristina Llorente, Samuel B. Ho, UC San Diego and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System; Derrick E. Fouts, Jessica DePew, Kelvin Moncera, J. Craig Venter Institute; Peter Stärkel, St. Luc University Hospital; Phillipp Hartmann, Peng Chen, David A. Brenner, UC San Diego; Lora V. Hooper, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.