A Bottle, a Postcard, and a Mystery

Chance find of a message in a bottle illuminates long history of ocean research

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Share This:

Article Content

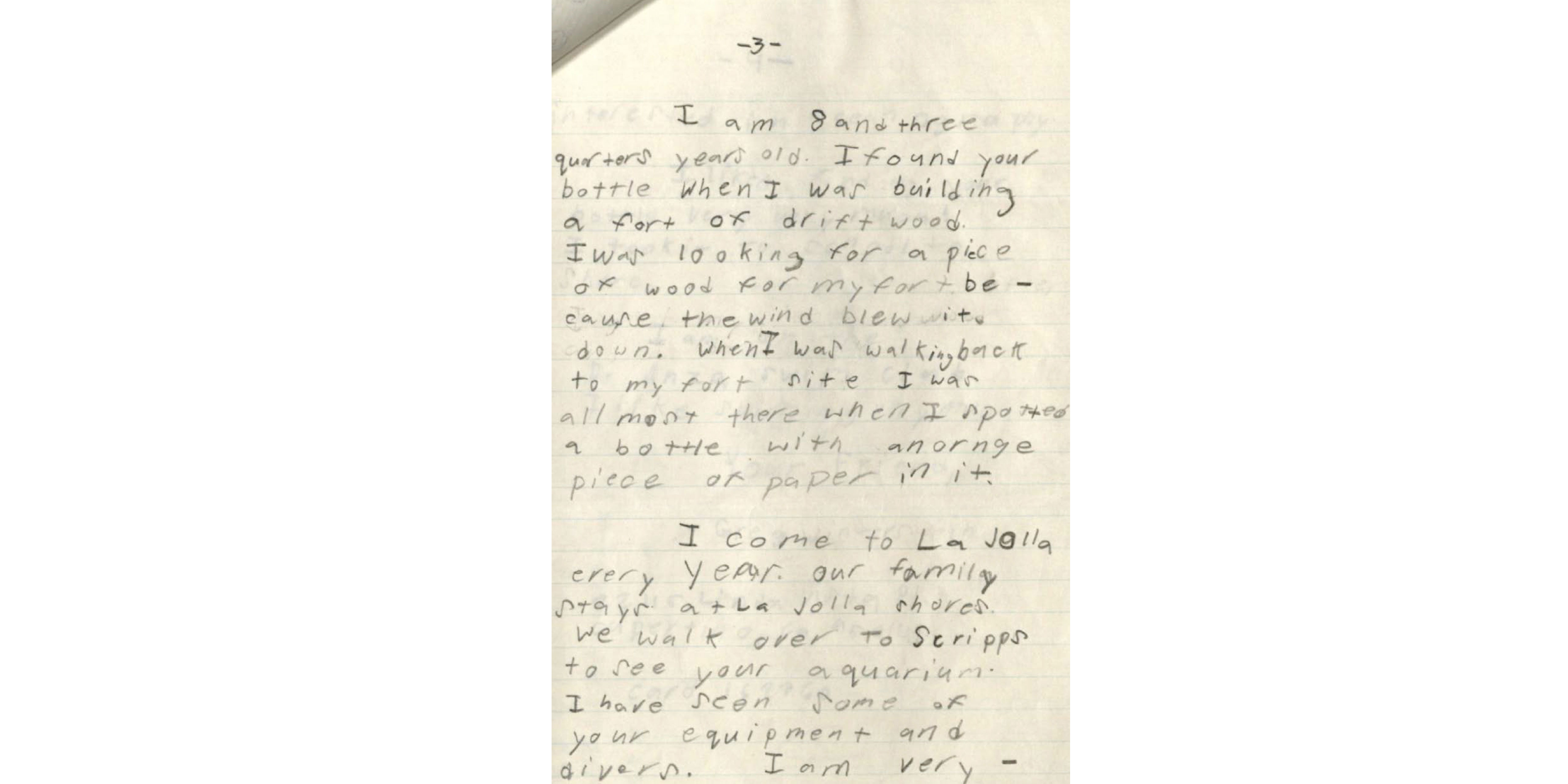

We know that sometime between August 1959 and June 1960, a message in a bottle was dropped in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California by scientists.

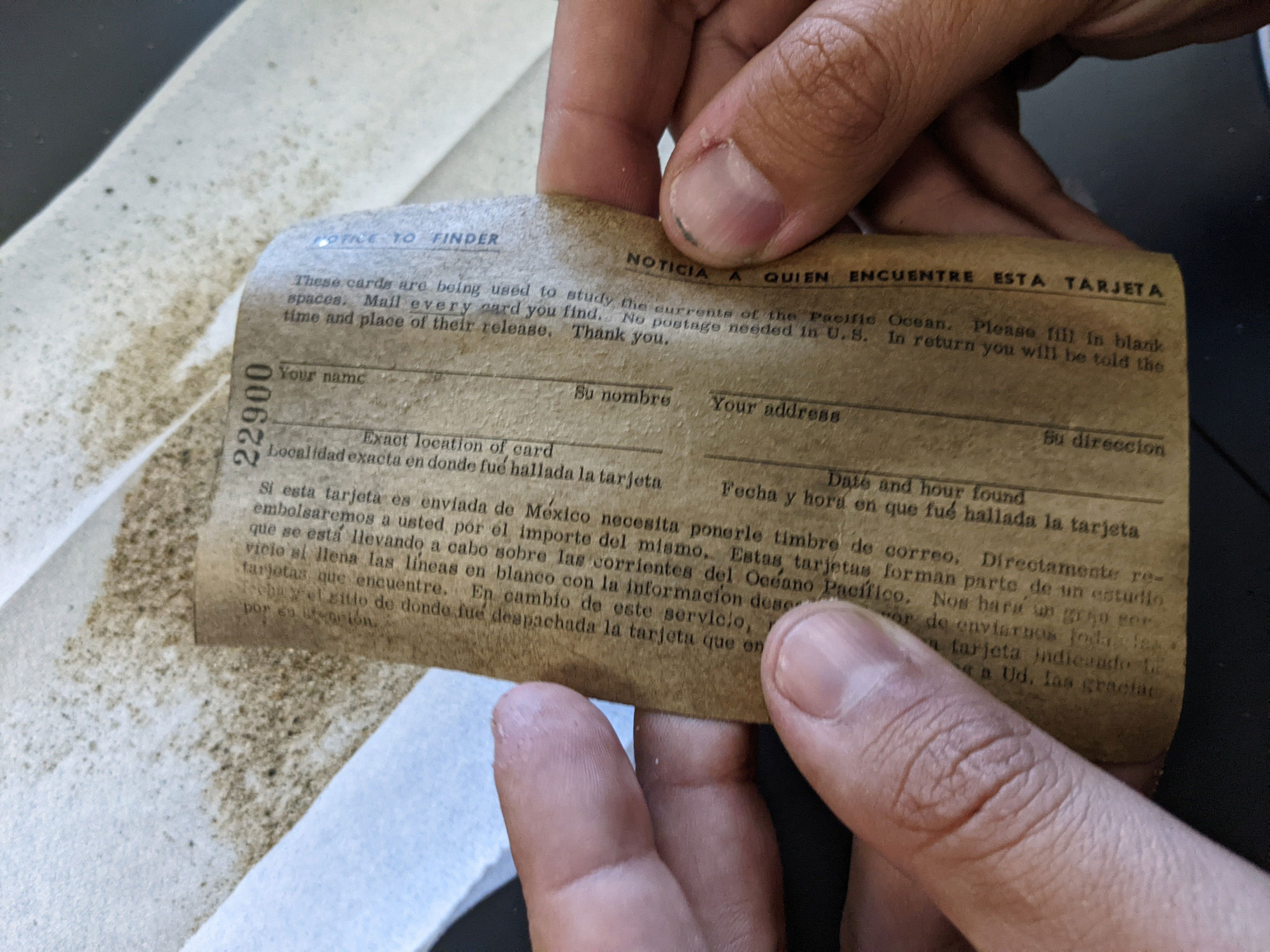

We know it had to be then because it was released as part of a program to study current drift that reports say lasted from 1954 to June 1960. The message was a numbered return postcard with postage of three cents, which was the rate the U.S. Postal Service put into effect on Aug. 1, 1959, hence it must have been dropped in those final months of the program.

And now we know that the postcard numbered 22900 has been recovered, on June 17, 2022. On that date, a bit of the heritage of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego re-emerged more than 60 years after the project’s end. The bottle and its message were found 150 feet from the high tide line at a spot in San Luis Obispo County, Calif., half-buried in a sand dune.

“I only noticed it because the glasswork was interesting,” wrote Paul Phelps, who was conducting a survey of plovers, a species of shorebird, for the California Department of Parks and Recreation at Oceano Dunes. “There was a card in the bottle with a form that asked me to mail back the card with information about when and where it was found to 'Scripps Field Annex Building 341,' which seems to no longer exist.”

The building indeed no longer exists but the program behind the bottle drop does. Researchers from the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI) program had deployed 52,650 bottles in the California Current over six years. A 1963 report on the project said that 2,439 had been returned by that time.

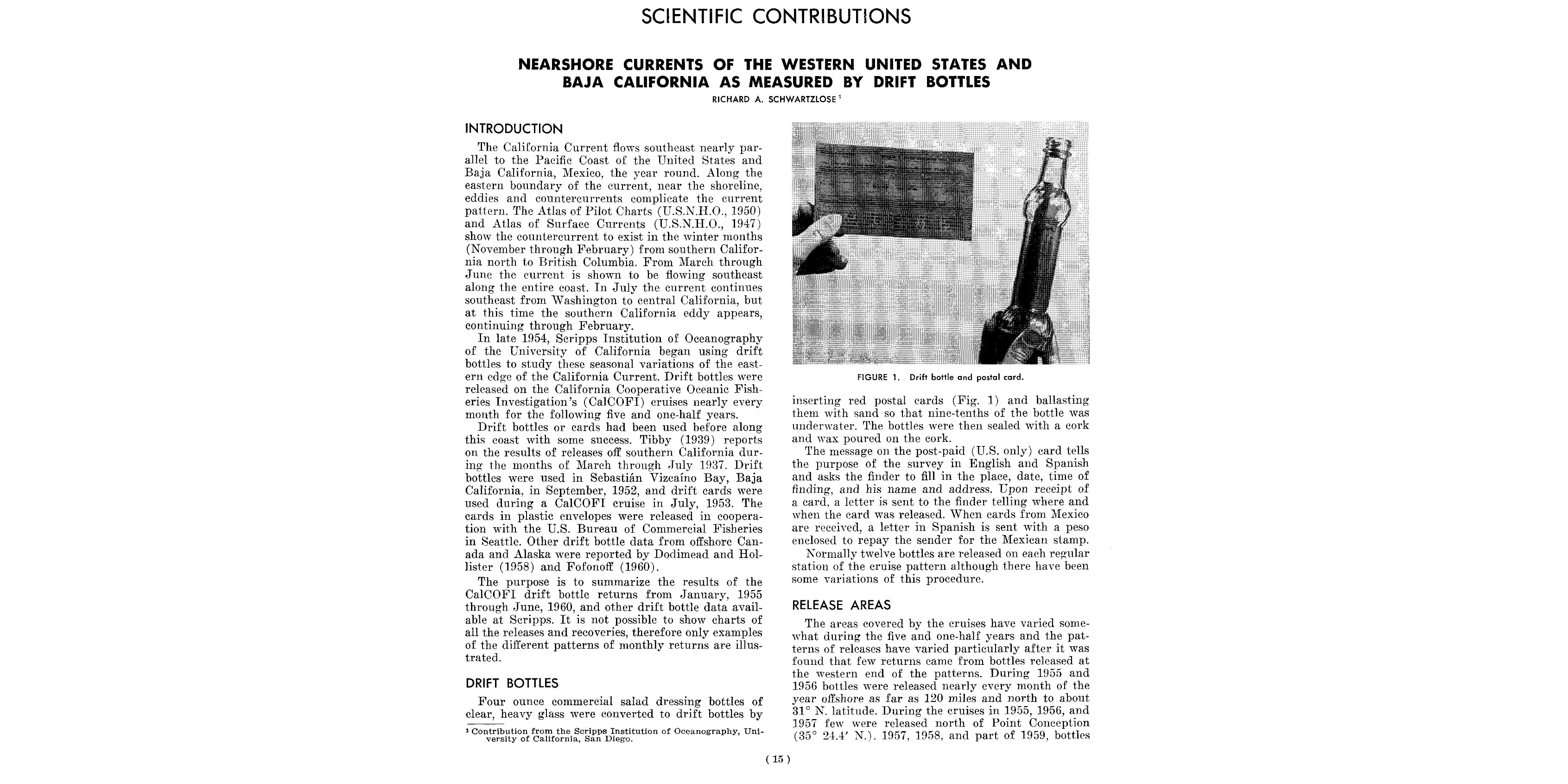

The bottle found by Phelps was, like all the others put in service, a rinsed-out salad dressing bottle. Scientists had originally sealed the bottles with corks and then dipped wax around the cork. When Phelps found the bottle, the cork and wax were gone but a plug of congealed sand had been protecting the contents. Inside were directions written in English and Spanish on what to do with the postcard if found. If Mexican citizens found and returned it, researchers wrote back and reimbursed them with one peso for the stamp.

The 1963 report notes that the southernmost drift of any returned postcard was by a bottle dropped off Punta Abreojos in Baja California and found in Acapulco in November 1959. “This was a minimum distance of 1,040 miles at a minimum speed of 0.23 knots,” the report said. The northernmost drift of any bottle released was by one dropped off San Clemente Island off San Diego and recovered off Vancouver Island in British Columbia. It traveled north during a countercurrent season that took place in 1957-58, revealing new details about the variability of the predominantly southbound California Current.

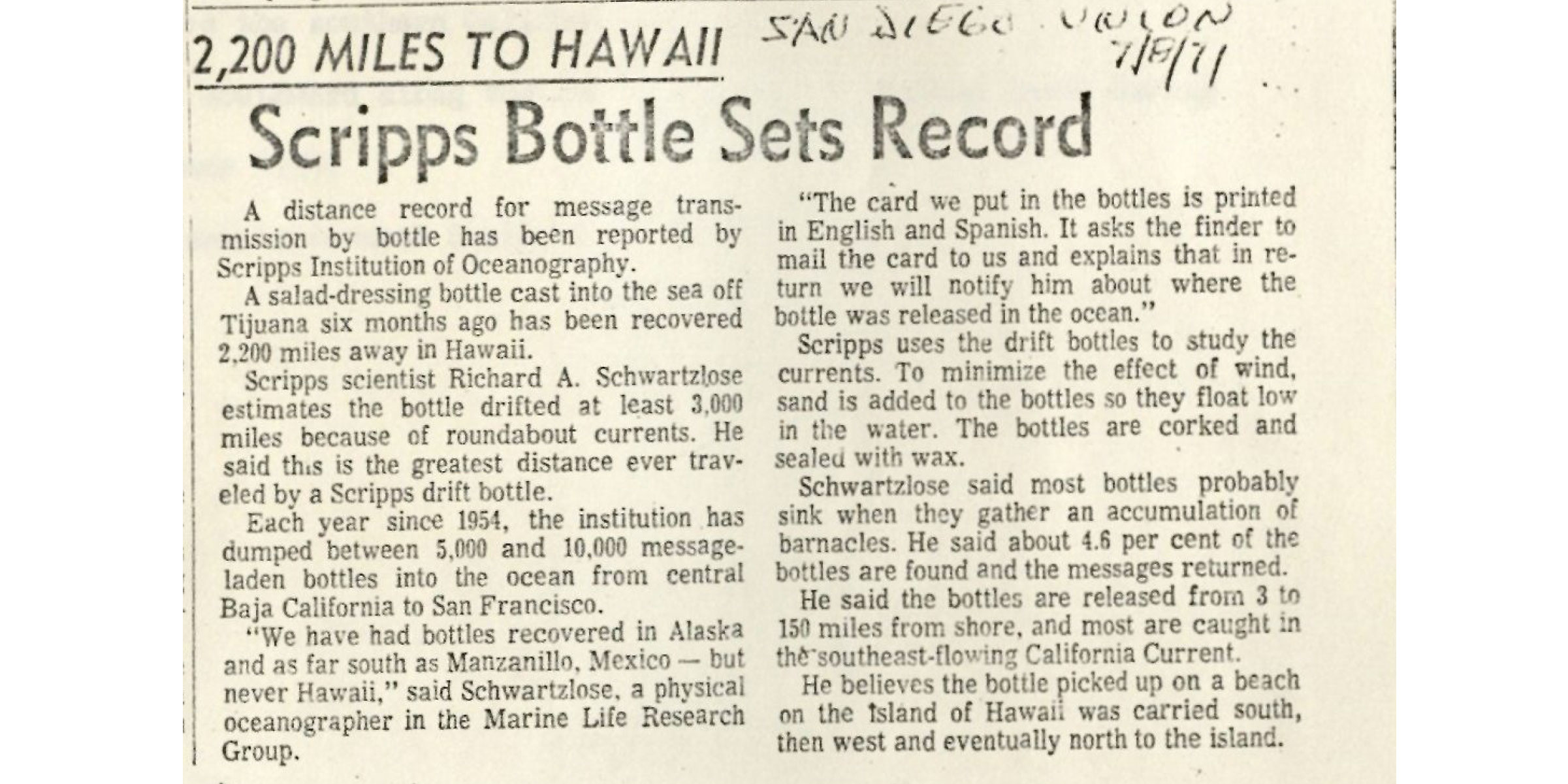

The 1950s program was actually one of several that CalCOFI has undertaken over the decades. Similar drift experiments using bottles with messages were conducted from the 1960s to the 1980s. A bottle from one of them set a distance record, making it to Hawaii in 1971, 2,200 miles from its launch point off Tijuana, Mexico.

"CalCOFI exists as the world's largest and longest ocean ecosystem monitoring program, spanning most of the last century,” said Scripps Oceanography marine biologist Brice Semmens, the current director of CalCOFI. “Early studies on ocean currents, such as this one, were fundamental to understanding connectivity in the ocean and atmosphere, and fed key discoveries such as the processes driving the El Niño–Southern Oscillation – a phenomenon that drives global weather patterns. In a modern context, CalCOFI monitoring continues to support new discoveries, often using emerging techniques that weren't dreamed of when the program began. These new modes of observing are more critical than ever, as the coastal ocean here in California undergoes increasingly rapid change.”

Long-term observations are a hallmark of Scripps Oceanography science, in deference to a truth of natural Earth system science that data become exponentially more valuable when gathered over long periods of time. Such programs at Scripps include the Keeling Curve measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide, initiated in 1958, the Shore Stations ocean temperature and salinity measurements starting in 1916, and the relative newcomer Argo, a network of robotic floats launched in 1999 that reached full coverage of all ocean basins in 2007. As for CalCOFI, it was started by state officials and scientists in 1949 with the initial goal of understanding why one of California’s most commercially important fish species, sardines, started to vanish earlier in the decade.

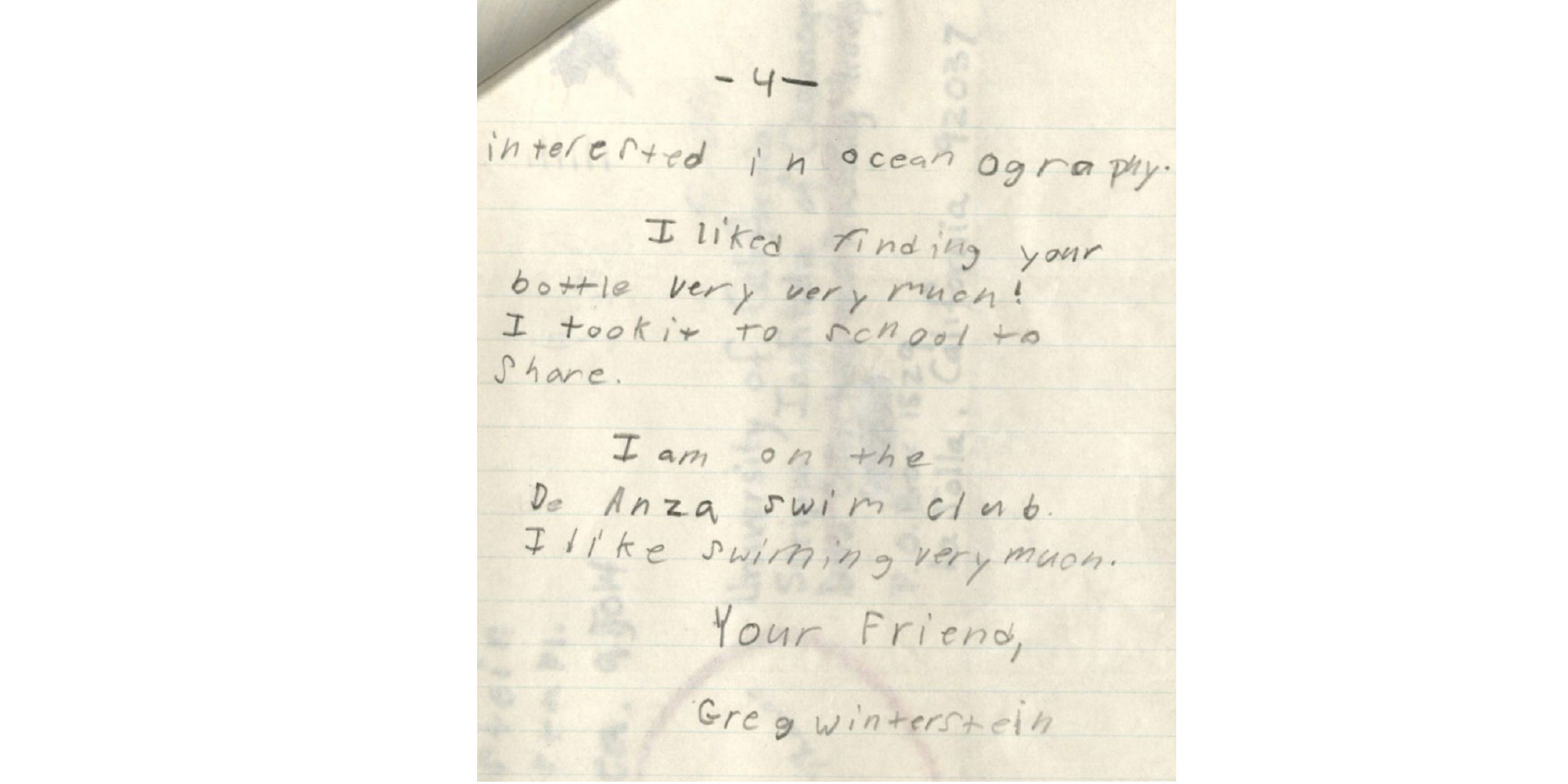

Phelps notified Scripps Oceanography about his find after doing some research and dutifully filling out the postcard.

“The card states that only after Scripps received the card would I be given the time and place of the bottle’s release in return,” he said in an email.

The people who would have made that promise have passed on. Project leader and author of the 1963 report, Richard Schwartzlose, died in 2017, according to his widow, Phyllis Schwartzlose, a resident of Solana Beach, Calif.

So where was bottle #22900 released? A search through log books and correspondence from over the years nets nothing. Unfortunately, there appears to not be a mention within existing records.

The bottle, though, will get a new home as members of the Scripps Oceanography Heritage Committee, a group of volunteer researchers and staff tasked with preserving institutional history, create a display for it on campus.

Share This:

You May Also Like

UC San Diego is Strengthening U.S. Semiconductor Innovation and Workforce Development

Technology & EngineeringStay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.