UC San Diego Literature Professor Brings Famed Japanese Filmmaker to Campus

Published Date

By:

- Dirk Sutro

Share This:

Article Content

UC San Diego Department of Literature Professor Daisuke Miyao is interested in silent era films, but he also appreciates the connections between early films and modern cinema. His interests inspired him to invite Kuji Yoshida, a legendary figure of postwar Japanese cinema, with films famous in the 1960s, to UC San Diego Nov. 10, from 3:30 to 5:30 p.m., at the Price Center West Ballroom.

Professor Daisuke Miyao. Photo: Dirk Sutro.

Miyao’s own connections helped in coordinating the visit of Yoshida and his Japanese film-star wife Mariko Okada, who will be present when two of Yoshida’s films are screened during the San Diego Asian Film Festival, Nov. 5 – 14.

“Yoshida is one of my favorite Japanese filmmakers, partly because he writes fascinating essays and theoretical articles about film,” Miyao said. “He is a very intellectual filmmaker. His films are art films in a broad sense—they are very political, very critical of the modern history of Japan. At the same time, his films are very beautiful.”

Miyao, who recently joined UC San Diego’s literature faculty as Hajime Mori Chair in Japanese Language and Literature and received a 2015 NEH Summer Grant, met the film festival’s Artistic Director Brian Hu through a mutual friend last year when Miyao attended the festival as a fan. Afterward, he and Hu began discussing how Miyao might participate during this year’s film event, so Miyao selected two of Yoshida’s films.

The first film called, “Eros + Massacre” (1969), starring Okada, is a biopic about early 20th century Japanese anarchist Sakae Osugi. In 1923, Osugi, his lover Noe Itō and his nephew were arrested and beaten to death by military police. “Eros,” screens Wed., Nov. 11, 6:30 p.m. at the Museum of Photographic Arts in Balboa Park.

The second Yoshida film, “Coup d’Etat” (1973) focuses on Ikki Kita, a socialist whose ideas led to a failed military coup in 1936, followed by Kita’s execution in 1937. “Coup d’Etat” screens Thurs., Nov. 12, 6:30 p.m., also at the Museum of Photographic Arts.

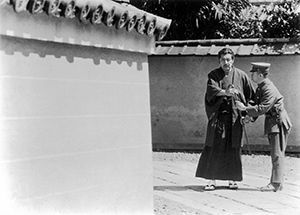

Image from the film, “Eros + Massacre” (1969). Photo: Courtesy of Kuji Yoshida.

Miyao explained that Yoshida is often associated with the French New Wave of rebellious filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, who experimented with narrative structure, handheld cameras and natural lighting.

“Yoshida was part of the Japanese new wave,” said Miyao, whose UC San Diego office is lined with DVDs ranging from Japanese silent films to American film noir. “His concerns were how Japan, especially the government and intellectuals, tried to incorporate international ideas about aesthetics, modernity and westernization. His films face those ideas from a modern perspective.”

Miyao added that Yoshida’s movies are period films, set in the 1920s and 1930s, but with scenes in which people of the 1960s interview the people who are experiencing things during the former time period, by way of flashbacks and voiceovers. This makes the films both period and contemporary dramas.

Miyao’s research is published in his recent books, “The Aesthetics of Shadow: Lighting and Japanese Cinema” (2013) and “Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom” (2007)—Hayakawa was a star of Japanese silent films.

Image from Yoshida’s “Coup d-Etat” (1973). Photo: Courtesy of Kuji Yoshida.

“Visually speaking, silent films are fascinating to me,” Miyao said. “When cinema obtained spoken words I think visually speaking it became a little degraded because it’s easier to use words to explain things. During the silent period they had to explain things visually, and they developed the visual language in a very crafty manner. I think the period around 1926 and 1927 was the high time of cinema as a visual medium.”

Miyao’s interest in early film will continue with his next book, which will explore the impact of films by the Lumière brothers. In December 1895, the first theatrical screening of a Lumière film took place in Paris. Some film historians mark this event as the beginning of cinema, which means that December 2015 is its 120th anniversary.

“In the beginning, cinema was purely a visual art form, and I wanted to go back to that period to learn not only about the stories but about the technologies and technical issues,” Miyao said. “Curiously, cinema studies courses these days do not really consider technological or technical aspects of films. They focus on political issues, thematic or narrative techniques, those things. I wanted to bring back this dialog between the people who are making films and the cinema-studies people who are talking about them.”

Miyao noted that Yoshida’s San Diego appearances are an extension of this same dialog. For more information about Yoshida’s films and the San Diego Asian Film Festival, visit the website.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.