Two-Sided Coin: Engineers for Exploration Program Pays Off for Students and Scientists

Story by:

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

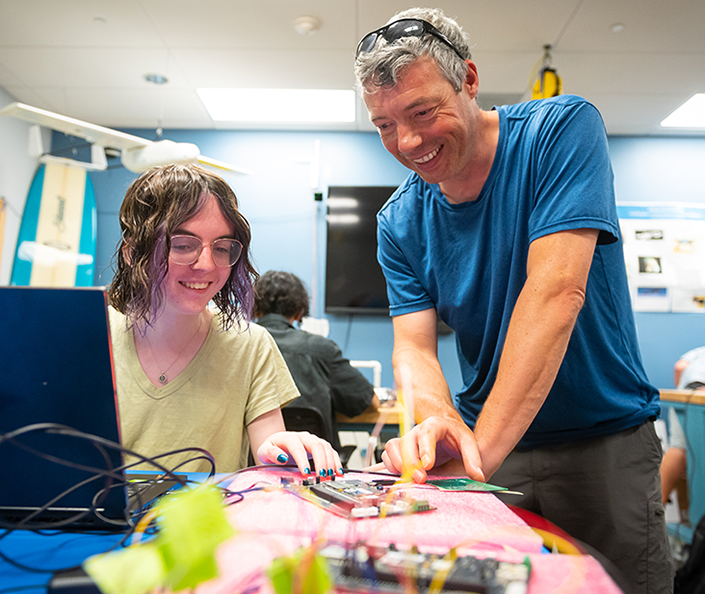

As participants in the Engineers for Exploration (E4E) program at the University of California San Diego this summer, Josie Dominguez, Jordan Reichhardt and Emily Thorpe are working as part of a team to figure out how to create the next generation of “Smartfin” technology, a surfboard-mounted sensor that collects and uploads information to track the health of our oceans.

The students are enthusiastic about the opportunity. “The biggest thing I am getting out of this is hands-on experience with embedded systems and printed circuit board design,” said Dominguez, an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz who is now considering graduate work in biomedical engineering because of her E4E internship. “These skills are not usually taught while at school even though they are very important for a career in hardware.”

The E4E program brings together students like these with real-world research projects from scientists near and far.

Ryan Kastner, a professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering, noted the program has worked to benefit both students and researchers since he and Qualcomm Institute (QI) Research Scientist Albert Lin first founded it in 2010. Their first project involved undergraduates in Lin’s National Geographic-funded quest to find the tomb of Genghis Khan. The program took off from there.

“I think the students get a ton out of it,” Kastner said. “These are real systems with users who are really keen to use them, develop the technologies, and get publishable data to better understand their scientific problems.”

“The real-world problems give an extra depth to the engineering challenges,” added Curt Schurgers, an Electrical and Computer Engineering faculty member and QI affiliate who co-directs the program with Kastner. “In contrast to homework, students are exposed to problems that may or may not have a solution. Students have the opportunity to contribute to causes that they're passionate about—say, saving an endangered animal or monitoring an ecosystem. You don't have to convince them this is important—that’s baked in.”

E4E intern Reichhardt, who attends California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, agreed. By working on Smartfin, developed from a partnership between Surfrider Foundation and the UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography (led by alumnus Philip Bresnahan, now a faculty member at University of North Carolina Wilmington), Reichhardt and her teammates are helping to collect crucial data close to the shore in what’s known as the surf zone, where the seafloor is too shallow and conditions too rough for other data collection methods, such as off-shore buoys.

“This summer, I am getting to further my passion for environmentalism, all while developing critical electrical engineering skills,” said Reichardt.

Sought-After Summer Spots

While Engineers for Exploration runs year round, with 50 or 60 UC San Diego undergraduate and master students working part-time during the academic year, the summer is a critical time in the program’s lifecycle.

“In the summer, the interns are working full-time, 40 hours a week,” said Kastner. “The summers are when everything comes together. It’s a good time, a fun time, for us, because there's so much going on and so much progress.”

Because many of the summer interns share space in the dorm and work together on projects, Schurgers notes that there’s a sense of solidarity among the summer interns. “There’s a cohort feel,” he said.

A National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Experiences for Undergraduates grant, which was recently renewed for its 11th year, is one cornerstone of summer funding, supporting 10 of the 18 to 20 summer interns with a salary, lodging and a travel budget. Other funding for E4E is provided by UC San Diego sources, including QI and the Jacobs School (both the Computer Science and Engineering and Electrical and Computer Engineering departments), as well as industry sponsors such as Northrop Grumman, National Instruments and MathWorks.

Hundreds of applications flood in from across the country for the NSF-supported summer internships. According to the grant’s priorities, many of the spots go to students from institutions with more limited opportunities to conduct research than at UC San Diego, a top-tier research university.

Thorpe, an intern who attends Macalester College in Minnesota, appreciates the way the program has broadened her horizons in interdisciplinary work and fields not offered by her small, liberal arts institution: “I am really enjoying team work on a project bringing together electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and computer science,” she said of her work on Smartfin, adding she is now thinking of pursuing a master’s in robotics and Ph.D. in engineering.

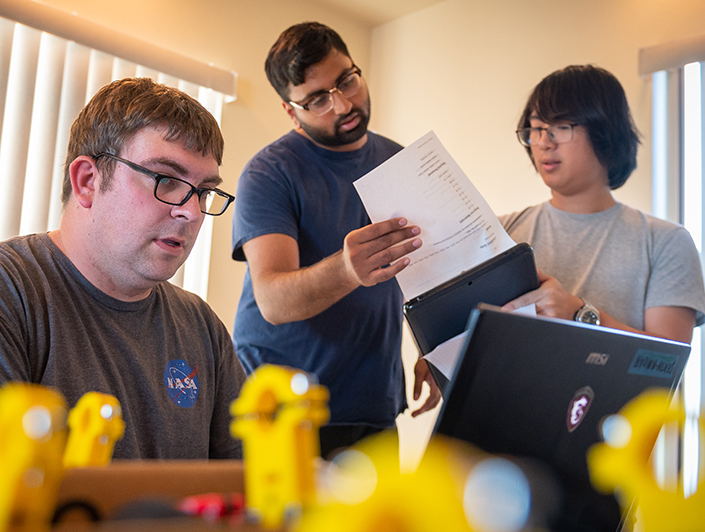

Providing continuity between the academic year and the summer session are the UC San Diego student project leads, who have often been steeped in a particular line of research for years.

“Those project leads have graduated to managing the project, managing other undergraduates and interacting with our collaborators, in conjunction with Curt and me,” said Kastner. “The project leads are the ones really driving progress. And they get great skills in terms of how to manage people and how to manage projects.”

Real-World Research Problems

The program’s scientific collaborators come to Engineers for Exploration via word of mouth with critical research technology problems that need solving.

“Typically we have eight to 10 different projects going on,” said Kastner. “Projects almost all revolve around remote sensing of some sort—building some sort of sensing platform with a goal of deploying that platform to collect data. We work a lot with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, which has a conservation research lab up near the Safari Park. Because we keep iterating the systems with feedback from the field, many of these projects have been going on for five, or even ten years. A successful project helps out our collaborators and make their lives better.”

One current project with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is the Acoustic Species Identification effort, which seeks to understand and monitor the rainforest ecosystem in Northern Peru through its soundscape. The zoo’s research team deployed dozens of small recorders to collect audio samples from across the region. Now the E4E students are harnessing machine learning and digital signal processing to help decode the terabytes of data, teasing out, visualizing and enumerating the sounds of different birds, mammals and other creatures—as well as voices, gunshots and revving motors indicating the presence of humans.

The bulk of other collaborators come from across UC San Diego. In one major project, called FishSense, E4E joins forces with Scripps Institution of Oceanography Associate Professor Brice Semmens and Reef Environmental Education Foundation to understand fish populations. In that project, E4E students are building underwater cameras that can be used by divers—both professional scientists and citizen-scientists—to record encounters with fish. Kastner explains that they ultimately hope to develop an underwater camera that, through photos or video, can automatically detect a fish, its species, its size, its mass and any distinctive individual markings—all at low cost, with technology that’s easy to use.

Other ongoing E4E projects include Mangrove Monitoring, which works with Scripps Oceanography Professor Octavio Aburto Oropeza to monitor landscapes in Baja Mexico with aerial surveys and 3D reconstruction; Baboons on the Move, which joins with biological anthropologist Shirley C. Strum, a professor emeritus and founding faculty member of the UC San Diego Department of Anthropology, and Associate Professor of Cognitive Science Federico Rossano, to track baboon troop movement in the plains of the Laikipia Plateau in Kenya; and Radio Collar Tracker, which supports the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance by offering a low-cost solution to tracking wildlife radio collars from the air.

E4E boasts of more than two dozen academic publications from these projects.

Ripple Effect

The E4E research projects overlap with Kastner’s professional interests in hardware acceleration, hardware security, and embedded and cyber-physical systems. On his website, Kastner describes his lab’s overarching goal as “to design, build, and prototype computing systems that are safe, secure, high performance, inexpensive, and low power. If this seems difficult, it is, and these challenges drive our research.”

E4E activities have spilled over into Kastner’s lab in a good way. “[E4E] informs my research by showing me really important problems that no one has been thinking about,” he said. “Because we’re building these systems, we discover underappreciated problems that are challenging and important. So it has been a way of driving some of my more theoretical research.”

Schurgers, who focuses on teaching and outreach, has also leveraged E4E in his work with the COSMOS pre-college program for high school students. “Our Engineers for Exploration students present to our COSMOS high school students to share the kind of cool projects they can work on as undergraduates in STEM fields,” he said, noting the presentations also offer a venue for the E4E students to practice the communications skills they learn in E4E seminars.

For the E4E students themselves, the experience can pay dividends over many years.

Nathan Hui’s trajectory, for one, has been shaped by E4E for almost a decade. As a UC San Diego electrical engineering undergraduate, he found E4E more relevant to real problems than the autonomous airplane competitions he had tried. After working on aerial monitoring with cameras mounted on helium balloons for the San Dieguito River Valley Conservancy, he hit his stride when he joined the Radio Collar Tracking project, throwing himself into signal processing and drone integration, including fieldwork.

“[In a trip to the Dominican Republic], we actually flew the drone around tracking baby iguanas as they were leaving their nests and dispersing,” he said. “I did two trips to the Dominican Republic that year. And throughout that time, we were constantly trying to test and improve the drone while we were stateside. The thing about fieldwork is we could see the actual struggles we were faced with, how the system does and doesn’t work in those real-world conditions.”

On top of the valuable technical skills, Hui’s appointment as student project lead generated growth on the management and mentorship side.

“One aspect of project leadership is figuring out how to best use each student’s skills,” he said. “In E4E, we don’t focus on a single engineering discipline. It’s very interdisciplinary and focused on systems building and systems engineering, so students have to adapt. It can be challenging when they’re struggling, and we need to figure out what can we do to efficiently get them up to speed. And it’s great to see when students absolutely thrive.”

Hui went on to earn a master’s degree in electrical engineering at UC San Diego based on his E4E work and landed a job in Teledyne RD Instruments in Poway, where he worked for several years.

Supporting Each Other

Hui continued to help out the E4E program, though, and when an opportunity arose to return to UC San Diego as an engineer—half time with E4E and half time with the Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative at QI—Hui jumped at the chance.

Now, as an E4E staff member, Hui works with Kastner and Schurgers to support the program, its students and its scientific collaborators. He is full of ideas about new ways the team might be able to iterate its own processes, such as new ways to approach data management and documentation. He’s also again immersed in student mentorship, figuring out how each student can get the most out of what E4E has to offer.

Students can feel the commitment to their growth and the atmosphere of cooperation that’s baked into Engineers for Exploration.

“I am really enjoying not only the technical skills I am learning and developing,” said intern Dominguez reflecting on her summer experience, “but more importantly the people in the program. Everyone at E4E is incredibly supportive of one another!” To learn more about E4E, visit the program’s website.

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.