Touch Goes Digital

After touch screens, researchers demonstrate electronic recording and replay of human touch

By:

Published Date

Article Content

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego report a breakthrough in technology that could pave the way for digital systems to record, store, edit and replay information in a dimension that goes beyond what we can see or hear: touch.

Deli Wang

“Touch was largely bypassed by the digital revolution, except for touch-screen displays, because it seemed too difficult to replicate what analog haptic devices – or human touch – can produce,” said Deli Wang, a professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) in UC San Diego’s Jacobs School of Engineering. “But think about it: being able to reproduce the sense of touch in connection with audio and visual information could create a new communications revolution.”

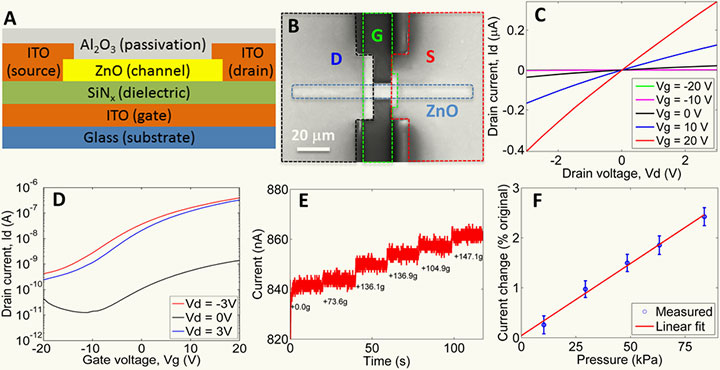

In addition to uses in health and medicine, the communication of touch signals could have far-reaching implications for education, social networking, e-commerce, robotics, gaming, and military applications, among others. The sensors and sensor arrays reported in the paper are also fully transparent (see optical image of transparent ZnO TFT sensor array at right), which makes it particularly interesting for touch-screen applications in mobile devices.

Wang is the senior author on a paper appearing in Nature Publishing Group’s Scientific Reports, published online Aug. 28. Co-authors include 11 researchers at UC San Diego, including fellow ECE professor Truong Nguyen, and UCLA professor Qibing Pei, whose team contributed to the sections on using polymer actuators for analog reproduction of recorded touch.

The first authors of this article, Siarhei Vishniakou and Brian Lewis of UCSD and co-authors Paul Brochu and Xiaofan Niu from UCLA, received the Qualcomm Innovation Fellowship (QInF) in 2012. (This project is partially supported by a Qualcomm Innovation Fellowship.)

In addition to professors Wang and Nguyen, other researchers on the project affiliated with the Qualcomm Institute at UC San Diego include recent Ph.D., Ke Sun, and Namseok Park, recipients of the institute’s Calit2 Strategic Research Opportunities, or CSRO, Graduate Fellowships in 2010 and in 2012, respectively.

“Our sense of touch plays a significant role in our daily lives, particularly in personal interaction, learning and child development, and that is especially true for the development of preemies,” said Nguyen, another senior author of this Scientific Reports paper. “We were approached by colleagues in the UC San Diego School of Medicine’s neonatology group to see if there was a way to record a session of a mother holding the baby, which could be replayed at a different time in an incubator.”

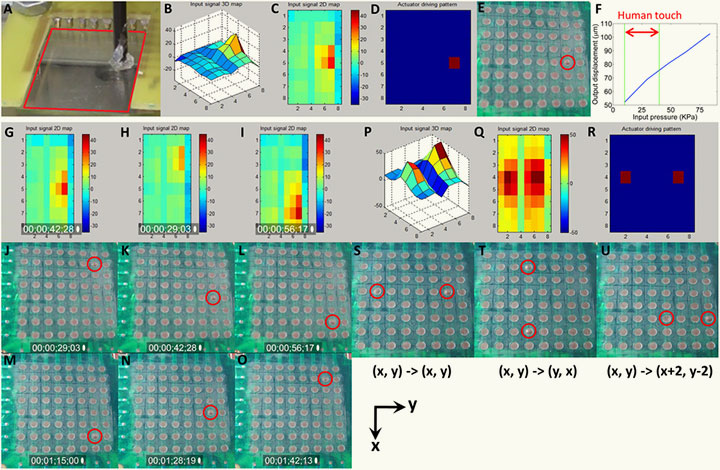

In their Scientific Reports paper, the researchers reported the electronic recording of touch contact and pressure using an active-matrix pressure sensor array made of transparent zinc-oxide (ZnO), thin-film transistors (TFTs). The companion tactile feedback display used an array of diaphragm actuators made of an acrylic-based dielectric elastomer with the structure of an interpenetrating polymer network (IPN). The polymer actuators’ actuation — the force and level of displacement — are modulated by adjusting both the voltage and charging time.

One of the critical challenges in developing touch systems is that the sensation is not one thing. It can involve the feeling of physical contact, force or pressure, hot and cold, texture and deformation, moisture or dryness, and pain or itching. “It makes it very difficult to fully record and reproduce the sense of touch,” said Wang.

As noted in the article, there has been significant progress on the development of flexible and sensitive pressure sensors, as well as tactile feedback displays for specific applications such as for remote palpation that could be used during laparoscopic surgery.

Digital replay, editing and manipulation of recorded touch events were demonstrated at various spatial and temporal resolutions. The researchers used an 8 × 8 active-matrix ZnO pressure sensor array, a data acquisition and processing system (sensor array reader circuit, computer, and actuator array driver circuit), and a semi-rigid 8 × 8 polymer diaphragm actuator array (click here to see video of the experiments).

The ability to digitize the touch contact enables direct remote transfer of touch information, long-term memory storage, and replay at a later time. “In addition, with the ability to reproduce and change the feeling of touch with both temporal and spatial resolutions make it possible to produce synthesized touch,” said UC San Diego’s Wang. “It could create experiences that do not exist in nature, as we have done with computer-generated imagery and synthesized music.”

While Wang and his colleagues recognize that the touch revolution is still in its infancy, and human trials will probably be needed to calibrate the optimal actuator response needed to conform to the human perception of pressure strength, which depends on actuator displacement (amplitude), frequency, and how much time the actuator spends in its on- or off-state (duty cycle). Yet, say the researchers, there is every reason to believe that their experimental system, by adding an extra dimension to existing digital technologies, could extend the capabilities of modern information exchange.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.