By:

Published Date

Song of the Trees

Composer John Luther Adams’ ‘The Wind Garden’ debuts as newest addition to Stuart Collection with public reception on Aug. 7

Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

It’s early morning and you’re strolling through a grove of eucalyptus trees when you hear the sounds, like bells softly trilling. Or is the wind whispering through the tall branches above? It is not your imagination; you have discovered the “The Wind Garden,” the 19th public art work of the renowned Stuart Collection at the University of California San Diego. In this installation by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Luther Adams, the leafed choir sings in response to the subtle shifts in light, wind and seasons.

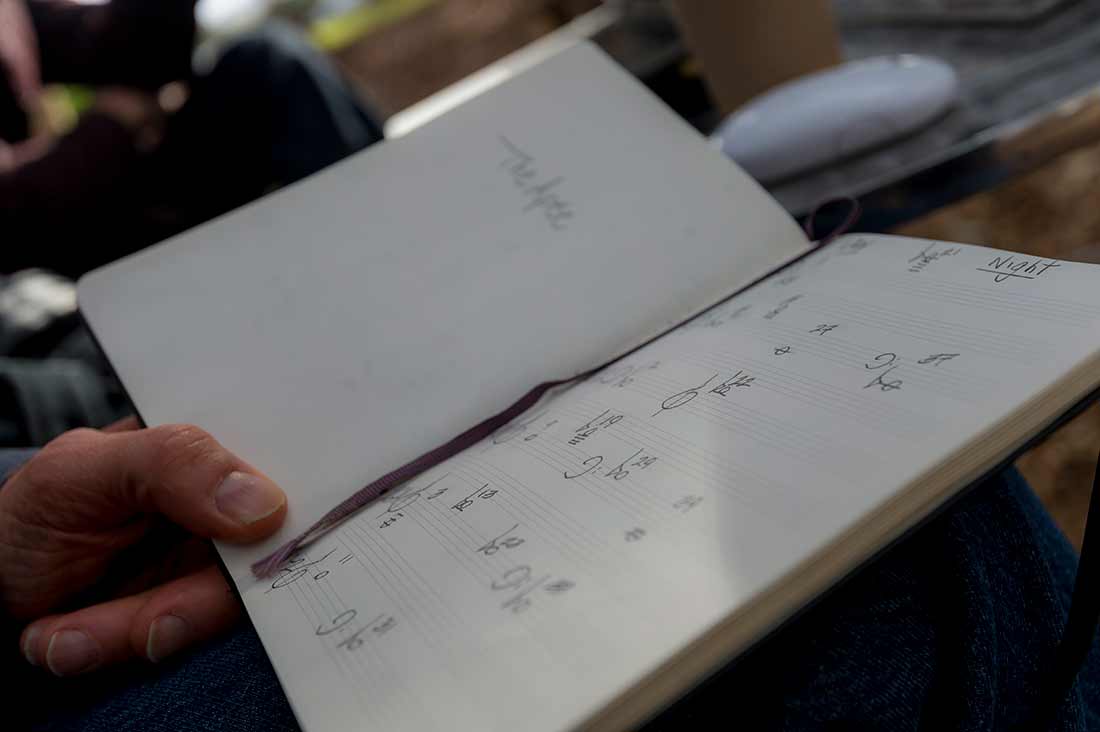

“The thing is alive; it’s thrilling to me,” exclaimed Adams as he made the final adjustments to the grove’s harmony. “Tuning this piece has been like trying to work with a team of wild horses. My job is to try to let it emerge and sing the way it wants to sing.”

The campus and local community are invited to explore the new installation at a public reception with the artist from 1-3 p.m. on Aug. 7. “The Wind Garden” is currently serenading visitors at all hours of the day and night—often to the surprise of unsuspecting passersby. The installation is meant to be essentially invisible. A team of composers, electronics engineers, arborists and data designers collaborated to bring the piece to life, utilizing a sustainable framework that leaves the grove virtually untouched.

To Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Luther Adams, the whole world is music. The Wind Garden is an invitation to listen and become better connected to our environment.

So how exactly can trees sing? Adams was invited to work with the signature landscape of UC San Diego, and chose a grove west of the Mandel Weiss Theatre. Thirty-two eucalyptus trees have been fitted with motion and light sensors that translate varying forces of wind and changing light patterns into sound instantaneously using sophisticated software. Speakers high in the canopy above project the sound, louder during strong gusts and sunny, summer weather; while subwoofers at ground level emanate more subtle, deep tones as darkness descends and winter prevails.

Each journey through the soundscape is a unique experience. The trees are not performing a finite composition; they are actively narrating the forces of nature happening in real time. Wherever you are in the grove, you are embraced by a polyphony of sounds, with no one ideal spot for listening. For those desiring a concentrated experience, they can linger in a small circular copse where the trees and speakers are more closely nestled. Others may choose to repose on one of the benches scattered through the space, made of reclaimed eucalyptus tree wood.

Instead of trying to evoke a certain experience or meaning, Adams’ work strives to cultivate subjective awareness and presence between ourselves and our environment. He explains, “The truth is, I am not interested in making music about anything. A piece may begin with a particular thought or image, but as the music emerges, it becomes a world of its own, independent of any extra-musical associations that I may have. The last thing that I want to do is tell you what to hear, to limit your experience, your imagination.”

Planting the seeds for a musical garden

It was in 2007 when Mary Beebe, director of the Stuart Collection, first heard Adams’ music performed live by the La Jolla Symphony and Chorus—directed by UC San Diego Professor of Music Steven Schick. Adams’ piece, “The Light That Fills the World,” brought the forces of nature into the concert hall. Beebe was drawn to the artist’s desire to create place with his music, something that the Stuart Collection’s site-specific works also strive to accomplish.

Stuart Collection Director Mary Beebe first heard Adams’ music a decade ago, and knew he would create something completely unique for the collection.

“We invited John because we knew it would be different than what we’ve done before,” said Beebe. “Terry Allen’s ‘Trees’ are recordings; ‘The Wind Garden’ is live response to the natural elements. Every work in the collection is a new adventure, a unique kind of experience.”

Adams, whose career as a composer has spanned four decades, has been creating sonic installations for the past 12 years. Many of his compositions were performed indoors. When he ventured to move his 99-drummer percussion piece, “Inuksuit,” outside to the unforgiving badlands of the Anza Borrego Desert, he was stunned to find the powerful pitch simply float away when unconstrained. It was then that he had an epiphany: why not create music that is intended to be heard outdoors from the start?

“Making music outdoors invites a different mode of awareness; you might call this ecological listening,” said Adams. “When we are in a concert hall, we close the doors and we try to seal ourselves off from the outside world. Outdoors, rather than focusing our attention inward, we are invited to receive messages not just from a composer or musicians, but from a larger world in which the music is sounding.”

The whole world is music

Nature has been a driving influence in Adams’ work since the beginning. After graduating from the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles, he followed his heart to the wild tundra of Alaska, the place where he says his life truly began. Here, he listened—to the aspen, the loons, the calving glaciers—to the music of the place. Sequestered in a one-room cabin studio, he tapped into the elemental and primordial noise sounding all around, leading him to compose music not simply about a place, but that had a geography all of its own.

In 2014, Adams was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his work, “Become Ocean,” an orchestra that addresses the effects of global warming and our changing Earth. A year later he received a Grammy for Best Contemporary Classical Composition for the same piece. The themes of climate change and conservation are integrated into many of his compositions. Before he committed his life to music, Adams served as an environmental activist until he decided that art can matter just as much as politics, and that nobody else could make the music he imagined but him.

Adams has been making music inspired by the natural world around him for four decades. The Wind Garden is his first permanent outdoor installation.

His works today, especially “The Wind Garden,” are imbued with this reverence for the earth. “Music is not what I do, it’s how I understand the world—and for me, the whole world is music,” said Adams. “As a composer, it’s my belief that music can contribute to the awakening of our ecological understanding. By deepening our connections to the earth, music can provide a sounding model for the renewal of human consciousness and culture.”

“The Wind Garden” is one of 19 site-determined installations that comprise the Stuart Collection, and each has a unique story to tell. The works, which have been sprouting across the 1,200-acre campus for the past three decades, represent an impressive assemblage of public art from visionaries such as Robert Irwin, Niki de Saint Phalle, Bruce Nauman and Kiki Smith. Visitors are invited to take a free, self-guided tour, perfect for families and art aficionados alike.

“What I like about the Stuart Collection is that you don’t run into it with a museum frame of mind; you just happen upon the works,” said Beebe. “Each is a completely different kind of experience, like a treasure hunt.”

All commissions are completely funded by private donations, including support from the Friends of the Stuart Collection, a growing network of arts enthusiasts. To learn more about the Stuart Collection, visit their website here.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.