By:

- Steve Schmidt

Published Date

By:

- Steve Schmidt

Share This:

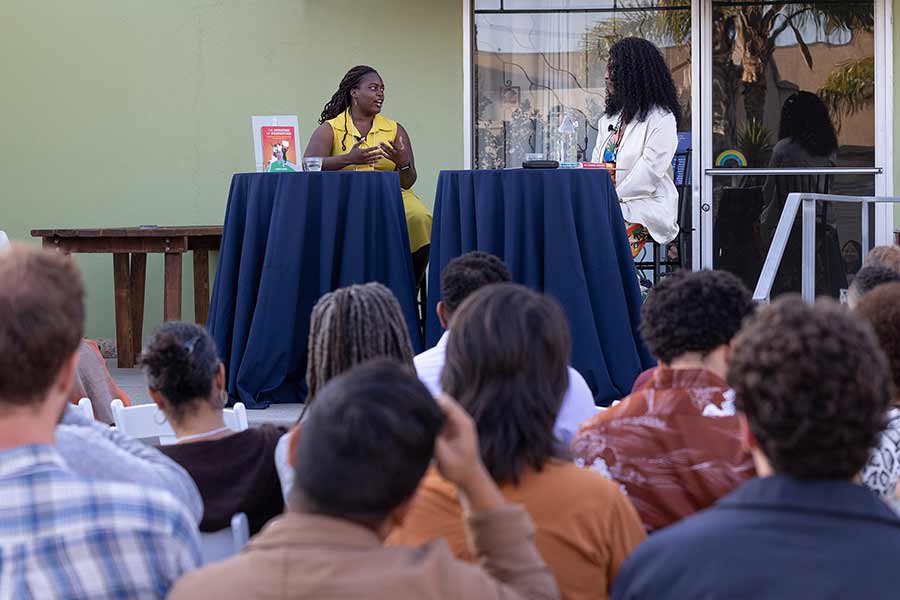

UC San Diego political scientist LaGina Gause discusses her new book, “The Advantage of Disadvantage. Photo credit: Kevin Walsh Photography.

Political Scientist LaGina Gause Probes the Power of Protest

Gause’s new book makes a novel argument: Protests by marginalized groups are more likely to spur change, despite the obstacles and backlash they often face when voicing grievances.

Protests have played a central role in the American story since the chaotic and colorful Boston Tea Party in 1773. Now, a new book by UC San Diego political scientist LaGina Gause adds a twist to the tradition.

In “The Advantage of Disadvantage,” Gause says data drawn from Congress and related sources point to an unconventional conclusion: Protests by poor and marginalized groups are more likely to spur change.

While demonstrations by Black, Latino and other historically disadvantaged groups often come at a high cost compared to white protestors and others, and can lead to a political backlash, the grievances that prompted such collective action are more likely to be addressed by lawmakers, according to her research.

“Protests can be the only effective way for a lot of communities to communicate,” said Gause, an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science in the School of Social Sciences. “And they help communicate what’s really important right now.”

Gause discussed her book at a public forum May 25 at Art Produce, a nonprofit community space in North Park. The event was sponsored by the Yankelovich Center for Social Science Research at UC San Diego, with the university’s Black Studies Project and the Future of Democracy program in the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

Grause said marginalized groups often have limited time and resources to participate in the political process, so protesting may be their most effective way to voice an immediate complaint. But coming together for collective action comes with its own obstacles. Many participants who are disadvantaged are also dealing with work demands, childcare needs and limited transportation options.

The protest scene itself may be risky. She writes in her book that law enforcement agencies are often quick to confront protestors from marginalized groups, while those from the dominant culture get the kid-glove treatment.

Case in point: The 2020 street protests that occurred in many cities after George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis. Many of these events were associated with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Gause points out that groups of predominantly Black demonstrators, even if protesting peacefully, were met by police in military-grade gear. Mass arrests and allegations of excessive force by law enforcement often followed.

Around the same time, white protestors with guns and military gear staged marches in the Midwest and other parts of the country against COVID-19 restrictions. Law enforcement generally did little in response, she said.

San Diego District 5 Councilmember Marni von Wilpert chats with other book forum attendees.

However, her analysis of congressional voting data and other records, along with surveys she conducted with legislators and staffers, found that collective action by marginalized groups tends to get more political traction.

She found that lawmakers are 46% more likely to support demands if the protestors are Black Americans compared to whites, and 40% more likely if they are Latino instead of white. In addition, legislators are 32% more likely to back demands made by low-income demonstrators compared to those with higher incomes.

“I argue that while elected officials are generally responsive to protest, they are exceptionally responsive to groups that protest despite high participation barriers,” she writes in “The Advantage of Disadvantage: Costly Protest and Political Representation for Marginalized Groups.”

She says lawmakers have a big incentive to respond because their re-elections may be on the line. The data suggest that those who are willing to protest at great risk to themselves are also motivated to hold officials accountable at the ballot box—a point not lost on lawmakers who want to stay in office.

But, she notes, there is often a gap between a legislator’s desire to address an issue and carrying out meaningful improvements.

Following the Floyd demonstrations, Gause said, “there were attempts by some legislators to really address a lot of issues around policing, and then they ran up against police unions or institutional rules that made it really hard to implement real policy change.”

Meanwhile, social media has emerged as a major driver of collective action. Online petitions, politically potent hashtags and other activist tools are commonplace. Social media was the starting point for organizing the recent protests across the nation related to abortion.

San Diego Union-Tribune columnist Lisa Deaderick leads a Q&A with Gause during the North Park event.

“The number of people who participated in pro-choice protests in recent weeks, I don’t know if that would have been possible without the Internet and its ability to inform people about where to be and why this issue is important,” she said.

While activism on social media can make an impact, it is not still not as effective as a high-cost demonstration, she argues, citing her research.

Protests in the U.S. have historically centered on expanding rights, from the women’s suffrage movement more than a century ago to the Civil Rights demonstrations in the 1960s. When these movements unfold, and the status quo is challenged, a backlash often follows.

That’s how Gause largely views the events of Jan. 6, 2020, when a mob of President Donald Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol.

“In a lot of ways, I think the Jan. 6 protests were kind of a backlash against Black Lives Matter, pro-immigration, women’s rights, all these different kinds of protests that were about expanding people’s rights,” she said.

Even the Boston Tea Party was led by a group fighting for more rights. In that case, colonists rebelling against political oppression and a lack of representation—themes heard at many protests today.

“The American colonists who revolted against the British Empire championed equal representation and equality under the law,” she writes in her book. “They declared that protest was crucial to realizing these ideals in a well-functioning democracy.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.