Massive Planetary Collision May Have Zapped Key Elements from Moon

New study traces moon evaporation and leads to questions about why Earth has so much water

By:

- Mario Aguilera

Published Date

By:

- Mario Aguilera

Share This:

Article Content

A celestial body about the size of the moon slams into a planetary body the size of Mercury in this artist's conception. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Fresh examinations of lunar rocks gathered by Apollo mission astronauts have yielded new insights about the moon’s chemical makeup as well as clues about the giant impacts that may have shaped the early beginnings of Earth and the moon.

Geochemist James Day of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and colleagues Randal Paniello and Frédéric Moynier at Washington University in St. Louis used advanced technological instrumentation to probe the chemical signatures of moon rocks obtained during four lunar missions and meteorites collected from the Antarctic. The data revealed new findings about elements known as volatiles, which offer key information about how planets may have formed and evolved.

The researchers discovered that the volatile element zinc, which they call “a powerful tracer of the volatile histories of planets,” is severely depleted on the moon, along with most other similar elements. This led them to conclude that a “planetary-scale” evaporation event occurred in the moon’s history, rather than regional evaporation events on smaller scales.

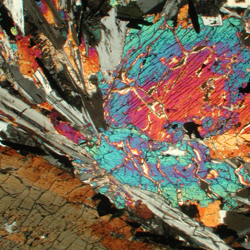

A cross-polarized transmitted-light image of a polished section of Apollo sample 12021.

The results are published in the October 18 issue of the journal Nature.

“This is compelling evidence of extreme volatile depletion of the moon,” said Day. “How do you remove all of the volatiles from a planet, or in this case a planetary body? You require some kind of wholesale melting event of the moon to provide the heat necessary to evaporate the zinc.”

According to Day, a gigantic planetary collision resulting in global transformations might be responsible for eradicating such elements. Day recently led a study in the journal Nature Geoscience that showed how such a collision might have brought precious metals such as gold and platinum to Earth, likely just after the solar system formed (http://explorations.ucsd.edu/research-highlights/2012/not-of-this-world/).

James Day

To derive the findings published in the new study, the researchers employed a mass spectrometer device, an advanced instrument that precisely measures the ratios of isotopes of a particular chemical element, which Day said revealed information not accessible even five years ago. Comparing the zinc composition of moon rocks with rocks from Earth and Mars revealed severe depletions in the lunar samples.

The researchers argue in the paper that such a disparity points to a large-scale evaporation of zinc, “most likely in the aftermath of the Moon-forming event, rather than small-scale processes during volcanic processes.”

The next stage of this research, Day said, is to investigate why Earth is not similarly depleted of zinc and similar volatile elements, a line of exploration which could lead to answers about how and why the earth is mostly covered by water.

Apollo 17 astronaut Jack Schmitt at the lunar rover near Shorty Crater, Taurus-Littrow valley of the moon. Image courtesy of J. Schmitt, the Apollo 17 crew and NASA

“Where did all the water on Earth come from?” asked Day. “This is a very important question because if we are looking for life on other planets we have to recognize that similar conditions are probably required. So understanding how planets obtain such conditions is critical for understanding how life ultimately occurs on a planet.”

Although the Apollo mission rocks were collected more than 40 years ago, the new study proves they are still offering new insights.

“They still have a lot of science to be done on them and that’s exciting,” said Day. “Hopefully these kinds of results will help push for future sample collection missions to try to more fully understand the moon.”

The NASA Lunar Advanced Science and Exploration Research and Cosmochemistry programs supported the research, which is representative of the work of planetary scientists at Scripps.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.