Leading Wearable Ultrasound Lab Creates a Breakthrough in Deep Tissue Monitoring

More effectively measuring tissue stiffness could help treat cancer, sports injuries and more

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Share This:

Article Content

Using ultrasound to examine the biomechanical properties of tissues can help detect and manage pathophysiological conditions, track the evolution of lesions and evaluate the progress of rehabilitation.

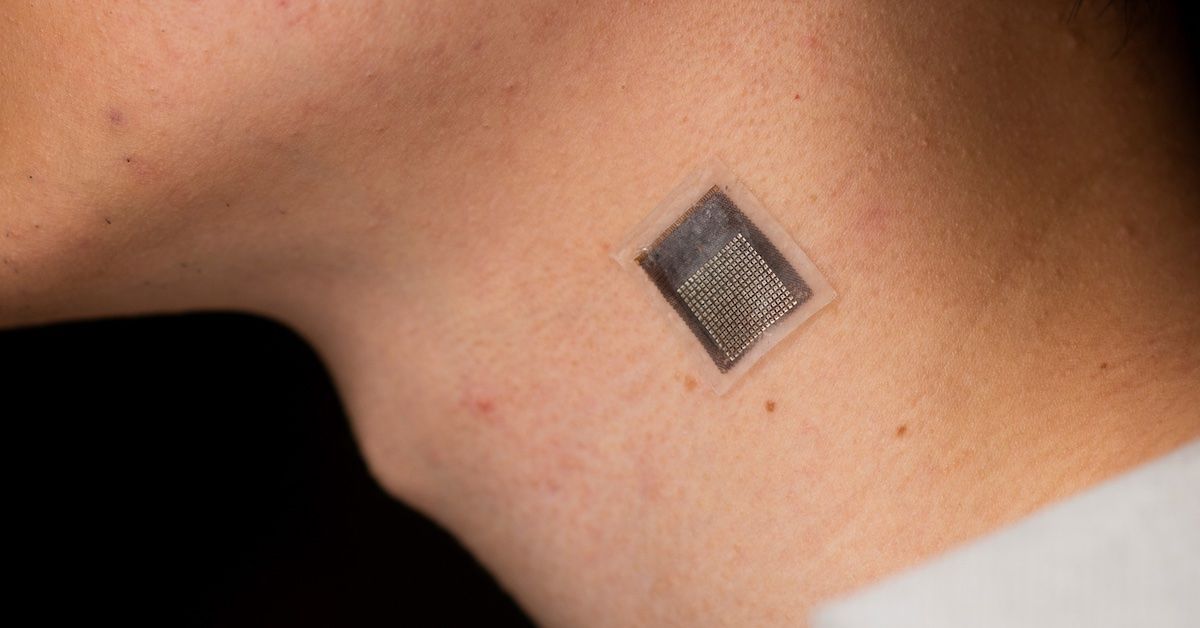

A team of engineers at the University of California San Diego, has developed a stretchable ultrasonic array that facilitates serial, non-invasive, three-dimensional imaging of tissues as deep as four centimeters below the surface of human skin, at a spatial resolution of 0.5 millimeters. This new method provides a non-invasive, longer-term alternative to current methods, with improved penetration depth.

The research emerges from the lab of Sheng Xu, a professor of nanoengineering at UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and corresponding author of the study. The paper, “Stretchable ultrasonic arrays for the three-dimensional mapping of the modulus of deep tissue,” is published in the May 1, 2023 issue of Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“We invented a wearable device that can frequently evaluate the stiffness of human tissue,” said Hongjie Hu, a postdoctoral researcher in the Xu group and study coauthor. “In particular, we integrated an array of ultrasound elements into a soft elastomer matrix and used wavy serpentine stretchable electrodes to connect these elements, enabling the device to conform to human skin for serial assessment of tissue stiffness.”

The elastography monitoring system can provide serial, non-invasive and three-dimensional mapping of mechanical properties for deep tissues. This has several key applications:

- In medical research, serial data on pathological tissues can provide crucial information on the progression of diseases such as cancer, which normally causes cells to stiffen.

- Monitoring muscles, tendons and ligaments can help diagnose and treat sports injuries.

- Current treatments for liver and cardiovascular illnesses, along with some chemotherapy agents, may affect tissue stiffness. Continuous elastography could help assess the efficacy and delivery of these medications. This might aid in creating novel treatments.

In addition to monitoring cancerous tissues, this technology can also be applied in other scenarios:

- Monitoring of fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver. By using this technology to evaluate the severity of liver fibrosis, medical professionals can accurately track the progression of the disease and determine the most appropriate course of treatment.

- Assessing musculoskeletal disorders such as tendonitis, tennis elbow and carpal tunnel syndrome. By monitoring changes in tissue stiffness, this technology can provide valuable insight into the progression of these conditions, allowing doctors to develop individualized treatment plans for their patients.

- Diagnosis and monitoring for myocardial ischemia. By monitoring arterial wall elasticity, doctors can identify early signs of the condition and make timely interventions to prevent further damage.

The Xu Lab: A leader in wearable ultrasound

Thanks to technological advances and the hard work of clinicians over the last few decades, ultrasound has received an ongoing wave of interest, and the Xu lab is often mentioned in the first breath as an early and enduring leader in the field, particularly in wearable ultrasound. The lab took devices that were stationary and portable and made them stretchable and wearable, driving a transformation across the landscape of healthcare monitoring.

Wearable ultrasound patches accomplish the detection function of traditional ultrasound and also break through the limitations of traditional ultrasound technology, such as one-time testing, testing only within hospitals and the need for staff operation.

“This allows patients to continuously monitor their health status anytime, anywhere,” said Hu.

This could help reduce misdiagnoses and fatalities, as well as significantly cutting costs by providing a non-invasive and low-cost alternative to traditional diagnostic procedures.

“This new wave of wearable ultrasound technology is driving a transformation in the healthcare monitoring field, improving patient outcomes, reducing healthcare costs and promoting the widespread adoption of point-of-care diagnosis,” said Yuxiang Ma, a visiting student in the Xu group and study coauthor. “As this technology continues to develop, it is likely that we will see even more significant advances in the field of medical imaging and healthcare monitoring.”

How it works

The array conforms to the human skin and acoustically couples with it, allowing for accurate elastographic imaging validated with magnetic resonance elastography.

In testing, the device was used to map three-dimensional distributions of the Young's modulus of tissues ex vivo, to detect microstructural damage in the muscles of volunteers prior to the onset of soreness and monitor the dynamic recovery process of muscle injuries during physiotherapy.

“We choose 3 MHz as the center frequency for the ultrasound transducer,” said Hu. “Since the higher the center frequency, the higher the spatial resolution, but the stronger the attenuation of the ultrasound wave in tissues, 3 MHz satisfies the requirements for both high spatial resolution and superb tissue penetration.”

The device consists of a 16 by 16 array. Each element is composed of a 1-3 composite element and a backing layer made from a silver-epoxy composite designed to absorb excessive vibration, broadening the bandwidth and improving axial resolution.

“We choose a pitch - the distance between the centers of two adjacent elements - of 800 μm, which is adequate for producing high-quality images, minimizing interference from neighboring elements and giving the entire device its good stretchability,” said Xiaoxiang Gao, another postdoctoral researcher in the group.

Specifications:

- Dimensions: approximately 23 mm x 20 mm x 0.8 mm

- Biaxial stretchability: 40%.

- Penetration depth: greater than 4 cm

- Highest signal-to-noise ratio: 28.4 dB

- Spatial resolution: 0.5 mm

- Contrast resolution: 1.74 dB

Overcoming challenges

Such technology must record the motion of scattering particles in the sample by ultrasound wave and calculate their displacement fields based on a normalized cross-correlation algorithm. The size of scattering particles is very small, resulting in the weak reflected signals. To capture such faint signals requires acutely sensitive technology.

Existing fabrication methods involve high-temperature bonding that can cause serious, irreversible thermal damage to the epoxy in the piezoelectric materials. As a result, the sensitivity of the transducer element degrades significantly.

“To address those challenges, we developed a low-temperature bonding approach,” said Hu. “We replaced the solder paste with conductive epoxy, which allows the bonding to be completed at room temperature without causing any damage to the element. In addition, we replaced the single plane wave transmission mode with coherent plane-wave compounding mode, which provides more energy to boost the signal intensity throughout the entire sample. Using these strategies, we improve the sensitivity of the device to make it perform well in capturing those weak signals from scattering particles.”

Next steps

“A layer of elastomer with known modulus, the so-called calibration layer, can be installed on our device to further obtain quantitative, absolute values of tissues' moduli,” said Dawei Song, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania and study coauthor. “This approach would allow us to obtain more complete information about tissues' mechanical properties, thus further improving the diagnostic capabilities of the ultrasonic devices.”

Additionally, advanced lithography, pick-and-place and dicing techniques can be adopted to further optimize the array design and fabrication, which can reduce the pitch and extend the aperture to achieve a higher spatial resolution and a broader sonographic window.

“It would be easier to explore opportunities working with physicians, pursuing potential practical applications in clinics,” said Gao. “Our device shows great potential in close monitoring of high-risk groups, enabling timely interventions at urgent moments,” said Gao.

Professor Xu is now commercializing this technology via Softsonics LLC.

Paper: Stretchable ultrasonic arrays for the three-dimensional mapping of the modulus of deep tissue. Coauthors include Hongjie Hu*, Materials Science and Engineering Program and Department of Nanoengineering, University of California San Diego; Yuxiang Ma*, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Xiaoxiang Gao*, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Dawei Song*, Institute for Medicine and Engineering, University of Pennsylvania; Mohan Li, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Hao Huang, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Xuejun Qian, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California; Ray Wu, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Keren Shi, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Hong Ding, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Muyang Lin, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Xiangjun Chen, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Wenbo Zhao, Department of Osteology and Biomechanics, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf; Baiyan Qi, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Sai Zhou, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Ruimin Chen, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California; Yue Gu, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Yimu Chen, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Yusheng Lei, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Chonghe Wang, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Chunfeng Wang, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Yitian Tong, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, UC San Diego; Haotian Cui, Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto; Abdulhameed Abdal, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, UC San Diego; Yangzhi Zhu, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Xinyu Tian, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Zhaoxin Chen, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Chengchangfeng Lu, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, UC San Diego; Xinyi Yang, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Jing Mu, Materials Science and Engineering Program, UC San Diego; Zhiyuan Lou, Department of Nanoengineering, UC San Diego; Mohammad Eghtedari, Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, UC San Diego; Qifa Zhou, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California; Assad Oberai, Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, University of Southern California; and Sheng Xu; Materials Science and Engineering Program, Department of Nanoengineering, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, Department of Bioengineering, UC San Diego.**

*These authors contributed equally

**Corresponding author

This work was partially supported by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) under agreement number FA8650-18-2-5402, the National Institutes of Health grants 1R21EB025521-01, 1R21EB027303-01A1, and 3R21EB027303-02S1, and 1R01EB033464-01, and the Center for Wearable Sensors at the UC San Diego.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Engineers Take a Closer Look at How a Plant Virus Primes the Immune System to Fight Cancer

Technology & EngineeringStay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.