Harnessing the “Monkey Mind”

Story by:

Published Date

Article Content

We’ve all experienced mind wandering. Perhaps you’re in a high-stakes business meeting but find your mind drifting away toward all the errands you need to run afterwards. Or, you’re working on an important class project but can’t help thinking about the crazy plot twist from the movie you watched the previous night. For whatever reason, your thoughts have taken an unexpected detour, leading you away from the task at hand.

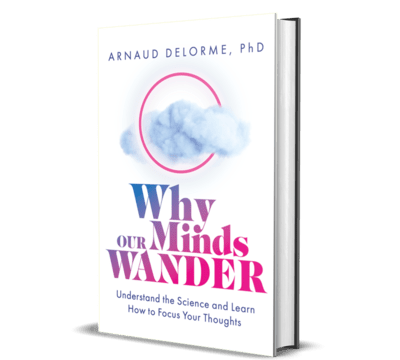

Now, what if mind wandering could be harnessed for the better? In his new book “Why Our Minds Wander: Understand the Science and Learn How to Focus Your Thoughts,” Arnaud Delorme, a research scientist at UC San Diego’s Institute for Neural Computation, provides a deeper look into this common yet complex experience. The introduction to the book was penned by the Jonathan Schooler, a distinguished professor of psychology at UC Santa Barbara, and received an endorsement from Deepak Chopra.

Delorme has been a part of the campus community since 2002 and is the main principal investigator behind the EEGLAB software, globally recognized as the most widely used tool for brainwave analysis. He is also a recognized researcher on the neural correlates of mind wandering and meditation.

In this Q&A with UC San Diego Today, Delorme shares insight into why mind wandering might be considered a good thing, how it can be helpful for boosting creativity and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mind wandering seems to be quite a universal phenomenon that many of us have experienced, whether you’re a student trying to concentrate in class or a business leader hoping to keep focused during an important conference call. Why did you decide to study this subject?

I first started studying mind wandering 20 years ago, and at that time, there wasn’t much existing research. I began exploring this topic when I started practicing meditation and noticed I was experiencing a lot of mind wandering during my sessions.

Is mind wandering the same thing as daydreaming?

That's a great question. Daydreaming is a type of mind wandering.

The book discusses much debate on the definition of mind wandering. It comes down to voluntary and involuntary thinking. I think most mind-wandering researchers would agree that mind wandering is usually involuntary. For example—you are reading, and then you lose track of what you are reading.

But, the line is blurred. If you’re washing the dishes and start to think about grocery shopping, is this mind wandering or is it voluntary thinking?

Daydreaming is in the middle of voluntary and involuntary. For example, you can start involuntarily dreaming about your upcoming vacation and then realize you are dreaming about your vacation.

In a society that values attentiveness in class and staying focused on work assignments, can mind wandering be seen as a positive thing?

There are debates about whether mind wandering is good or bad.

Some of my studies show that experienced meditators can learn to curb mind wandering. However, you cannot eliminate mind wandering entirely. In the Eastern tradition, the term "monkey mind" is recognized by meditators as referring to a distracted mind.

However, in Western psychology, experiments have shown that mind wandering can be helpful for creativity. When study participants are tasked with a creative assignment, such as coming up with potential uses for an object, they exhibit greater creativity when allowing their minds to wander naturally compared to when instructed to concentrate solely on the task.

In my research, I’ve shown that mind wandering could be interpreted as a type of microsleep during the day that lets your brain rest. Mind wandering can also be a process of the mind and the brain reprioritizing. For example—you've been watching a movie for one hour and the thought pops into your mind that you are hungry and need to eat.

In your book, you provide practical strategies for harnessing and refining the skill of mind wandering. Could you share some of these strategies that might be helpful for our university community?

The book—which is practical and more centered on well-being—includes different meditation exercises. You can't just ask people to stop mind wandering; you must use behavioral and meditation-derived mindfulness techniques.

One technique begins with journaling. In this exercise, you grab a sheet of paper and a pen, then sit for five minutes and write everything that crosses your mind. You then classify the types of thoughts; perhaps you’re thinking about yourself, the future or a thought triggered by a sound in the environment. There are around ten different categories of mind wandering, and by doing this exercise, you become aware of the types of mind wandering that you experience.

The book also includes breath-counting techniques and cognitive-restructuring techniques, such as reframing the thoughts that bother you.

Can the techniques used to manage mind wandering be used as a life hack for navigating college or work?

Yes, totally. If you are distracted in class, you are mind wandering too much. The techniques my book shares get more at the root of the issue.

Regarding the physiology of it, when you think about a thought all the time, it is reinforced. It's like a virus in your mind—the more you think about it, the more these networks are reinforced. There are techniques to let go of these thoughts. You have to convince yourself that this thought is not good for you.

Let's say you have credit card debt and that thought stresses you out or doesn’t make you happy. With these cognitive restructure techniques, when you realize that the thought doesn't help you, then your brain will realize it's not a good thought to have and reject it because it's not in your best interest.

If you had to pick one takeaway from your book, what do you hope readers come away understanding?

While it all depends on where people are in their development, sometimes there's a book that triggers an epiphany. By reading this book, you realize that you are not your thoughts. Sometimes thoughts just pop up in your brain—you don't have to have these thoughts all the time.

For me, if this book is useful for at least one person, then it has done its job.

You can't just ask people to stop mind wandering; you must use behavioral and meditation-derived mindfulness techniques.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.