Hands-on Chemical Engineering Course at UC San Diego Brings Students Out into the Light

Published Date

Story by:

Media contact:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

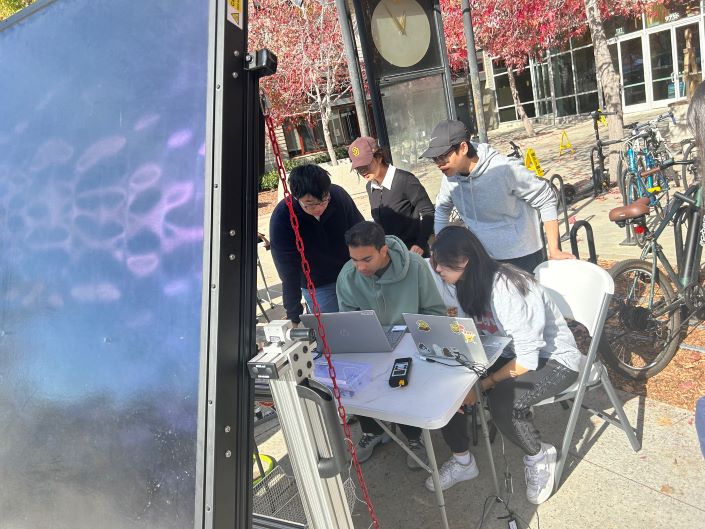

Students huddled around a laptop—this is a common sight on the University of California San Diego campus. But it’s less common when the students are outside, surrounded by pipes and hoses that attach a water tank to a large blue-black panel. A closer inspection reveals lots of colorful wires on a breadboard, lines of code on a computer screen and looks of concentration on the students’ faces.

Simply put, the students are trying to heat up water. But it may not be without some struggles.

"You are watching engineering because this is the kind of stuff we do,” said Aaron Drews, a teaching professor in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering in the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. Engineers start with an idea, he explained, and when they find out an idea isn't good, they go back and iterate on it, as they learn more.

Drews would know: these undergraduates are working on their capstone project in the junior-level lab course for chemical engineers that he designed and teaches.

Up until a few years ago, chemical engineering students didn’t have their own junior year experimental methods course; instead, they had to take another department’s course, which was designed specifically for mechanical and aerospace engineering students. So Drews tailored the new course for chemical engineers, with a few bonus goals in mind.

One such goal being that he really wanted to get the students out and about on the UC San Diego campus. Since he was an undergraduate, Drews has always been curious when he came across groups of people outside working on projects—from concrete canoes to rockets and robots—sometimes even while wearing hard hats. He wanted to build up similar excitement for not only bypassers but the students themselves.

And let the chemical engineers be visible to all. “We are physically on campus,” he said. “We are present out there.”

From lab to light

As he began developing the course, Drews involved James Findley de Regt, a research and development engineer also in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering. Findley de Regt’s overall philosophy on hands-on courses had him on board: “The engineering practical experience is truly important for the engineers,” he said.

Plus, Findley de Regt is heavily involved in the 4th year design lab course, which has open-ended experiments. So he was keen to help create a junior-level course that would help all the chemical engineering students have the experience and skills they would need to be successful in their senior courses.

Former student Josiah Konecky would agree: “I really like that it helps you get ready for your senior year courses,” he said. It helped him switch the mentality of doing mostly pen and paper homework to doing more projects and report writing. Konecky is currently a first year chemical engineering graduate student at UC San Diego and was the course’s most recent teaching assistant.

With Drews as the instructor and Findley de Regt as the lab manager, the pair has run the course five times now. Being the engineers that they are, they have tested and tweaked the course every time and are now ready for a sixth quarter coming up this spring.

The format has one lab per week for the first six weeks. What’s unique though is how the amount of structure changes over the course. In terms of instructions, explained Findley de Regt, the students receive over 40 detailed steps for their first lab, which drops incrementally all the way to only five basic steps for the last lab.

“We’re deliberately giving them less and less help as we move through the lab to get them ready for the fact that they will not be getting help the rest of the time in their lives,” he said.

Then comes the capstone project for the final weeks of the quarter. The students have open-ended accessibility to check out the equipment and take it out of the lab. They get very minimal instructions, and no instructors head out with them.

“There’s nothing else in our curriculum that gives them that level of responsibility and freedom to achieve a goal,” said Drews.

That goal being to collect some data from a solar collector to see if it actually performs as well as the manufacturer says it does. When Drews was considering potential capstone projects for the course, he wanted to take advantage of something San Diego has a lot of—sunlight. Of course, the sun moves throughout the day and each day has only so many usable daylight hours. So that sunlight is just one of many real-world variables in the project the students have to factor in.

Ray Ostrow, a 4th year chemical engineering student took the class last year. She returned as an undergraduate assistant or “grader” for the course. Ostrow recalled how her group had to take the equipment out on five separate occasions before they collected good data. Indeed, clouds thwarted one day, but other days had issues with the electronics or even saving the data.

“A lot of the people that I worked with are really smart people,” said Ostrow. “The fact that we were messing up as much as we were was a great reminder of how experiments rarely go off seamlessly, even if you do prepare them to the best of your ability.”

Hidden lessons

Given the level of complexity and that they have to figure it all out themselves, Findley de Regt estimated that for more than 75% of the students, this capstone project is the most challenging thing that they have undertaken in their undergraduate career to date. It goes beyond just the physical complexities of the lab work but also includes the psychological difficulties they’re having with it, he said.

The students also have to consider safety concerns, perhaps for the first time, added Drews. Not only do they need to be aware of how they themselves interact with the equipment but also how anyone in the public might interact with it, such as a power cord in the walking path.

“It forces the students to think about how their actions impact the world,” said Drews, “specifically how their engineering actions impact the world around them.”

For the capstone project, the students are in large groups, up to 12 members. That team experience requires them to work on soft skills, like how to communicate and operate with others, especially when everyone comes from different backgrounds and has varying skill sets.

Konecky remembered some of the coordination his team had to do outside of the actual experiment work, such as arranging their schedules, figuring out rotations so everyone got a lunch break and hauling all the equipment to the measurement site.

“It was really neat getting to work as a team and see how everyone can collaborate. Different people fell into different kinds of niches,” he said, “and it was just fun to see how that all panned out.”

Teamwork is definitely something the students should expect in the real world after graduation, according to Findley de Regt. The chemical engineering degree deserves more respect than it currently gets, he said, because it gives the graduate a broad base upon which to build other things. When the students graduate and go out into industry, they will often find themselves necessary members on teams full of people with wildly different backgrounds, he added. And all sorts of companies need chemical engineers, from the traditional petrochemical and mining industries to those working on battery, desalination or vaccine chemistries, even bioengineering startups. Ostrow liked how her hands-on experience with the solar collector showed a pathway to the clean energy industry.

Some disciplines actually refer to chemical engineers as process engineers, as they are responsible for turning something of low value into a product of high value. In the case of the capstone project, the students are using the solar collector to turn cold water (low value) into hot water (high value).

“It’s almost impossible to list all the things that are generated by processes because nearly everything that we interact with on a regular basis is generated through a process,” said Drews.

With this project, both Drews and Findley de Regt agreed that it’s succeeding in giving the students some sense of pride and excitement seeing others interested in what they’re doing.

Jennifer Mullin, faculty director of Experience Engineering at the Jacobs School of Engineering and a teaching professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, is glad the course is now part of the curriculum: “Providing rich learning experiences, such as these, are essential in engaging and preparing students, particularly sophomores and juniors who often lack experiential coursework, with the applied technical and professional skills they need to be successful in the engineering field.”

“One of the big things I love about running each new batch of students through the course is that when it comes together for them, they get a huge confidence boost,” said Findley de Regt. “They understand more about themselves and how to do stuff in the real world. And a lot of life is not difficult. It’s just complex, right?”

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.