From Lab to Clinic: The Muscle Physiology Lab at UC San Diego

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

As a physical therapist in the first part of his career, orthopedic surgery and bioengineering professor Samuel Ward, P.T., Ph.D., always preferred the patients that presented a challenge.

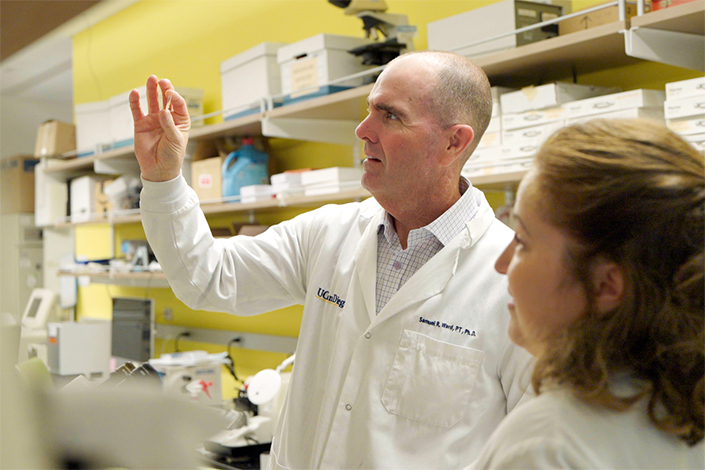

“I was immediately drawn into research because I didn’t have the answers I wanted for the patients I was seeing,” said Ward, who is also vice dean for research at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. “When you are working in research, you learn very quickly how comfortable you are operating in the realm of uncertainty. I found I thrived in it.”

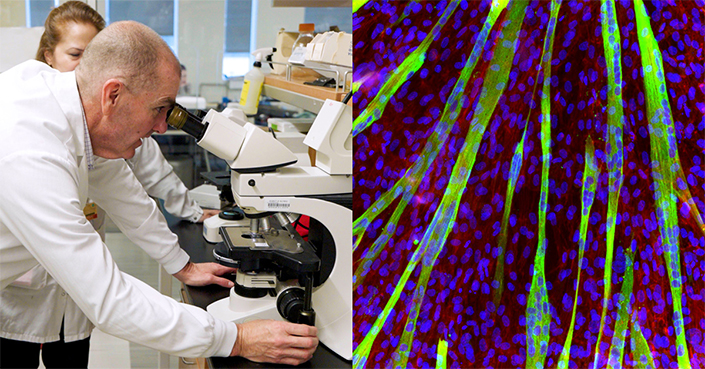

Today, Ward no longer sees patients as a physical therapist, but as the director of the Muscle Physiology Laboratory, located within UC San Diego’s Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute, he is leveraging his dual passion for clinical care and research to study how the human body works from a mechanical and physiological perspective and discover new ways to preserve, restore, and measure human motion.

“Even though few musculoskeletal diseases are fatal, they are often severely debilitating, because virtually every aspect of human health ultimately comes back to personal fitness and being active,” said Ward. “Musculoskeletal health is central to keeping people as healthy as possible for as long as possible.”

The power of translational research

The Muscle Physiology Laboratory is a collaborative, interdisciplinary research group that looks at every aspect of musculoskeletal biology, from “soup to nuts,” as Ward puts it. Their research interests include the biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system, regenerative medicine for musculoskeletal conditions, and even 3-D printing of muscle tissue. However, the common ground across all their research is that it is translational, with the ultimate goal of leveraging their discoveries in the clinic to improve patient health and outcomes.

In one notable example, Ward’s team collaborated with surgeons at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Sweden to develop and test a new approach to treating tetraplegia, the loss of function in all four limbs as the result of a traumatic spinal injury.

The team discovered a new, more effective way of completing tendon transfer surgeries, a procedure in which functional tendons are moved to replace a nonfunctioning tendon or muscle. Tendon transfer can help some people with tetraplegia regain key pinch, the ability to pinch your index finger and thumb the way you would hold a key.

“This can be the difference between being able to control an electric wheelchair and not being able to move independently, or between being able to feed yourself and needing an assistant,” said Ward.

However, restoring key pinch through tendon transfer has historically come at the cost of pronation, the ability to rotate the hand about the wrist. By leveraging biomechanical principles in the lab, Ward and his team discovered that with a small adjustment to how the transferred tendon is wrapped across the arm, it is possible to restore both key pinch and pronation simultaneously. In the decade since this technique was tested in the clinic, it has gone on to become the gold standard of tendon transfers for tetraplegia.

“When you’re starting off with severely limited function, anything we can restore or preserve is critical,” added Ward. “These are small motions that result in huge quality of life improvements for patients.”

An intellectual and economic multiplier

According to Ward, translational research like this is not just a strength of his lab, but of the entire UC San Diego campus. This is because, as the only academic health system in the region, UC San Diego positions the latest science alongside patient care, streamlining the process of turning discoveries into cures.

“Biomedical research is like a pyramid; you have a small number of cures at the top, supported by a wide base of research infrastructure, the people and technology that allow us to make discoveries,” he said. “The strength of this scientific horsepower comes to bear when you position it next to an equally strong clinical enterprise. This is the power of translational research.”

However, this work doesn’t happen out of thin air. It takes substantial resources to drive these breakthroughs, resources that would become much scarcer if proposed cuts to the National Institutes of Health’s indirect costs are implemented. These indirect costs support vital shared facilities that are used every day by researchers across the entire campus, not just by the Muscle Physiology Lab. They also support the cost of hiring and retaining skilled research personnel.

Without this funding, the overall volume of scientific research will drastically decrease, as would the future scientific workforce; cuts to indirect costs leave fewer resources available for training the next generation of researchers.

“This is the intellectual multiplier that we’re posed to lose,” added Ward, who notes that this intellectual multiplier is also an economic one. According to the NIH, each dollar of research funding in 2023 resulted in $2.46 of economic activity.

However, to Ward and other scientists like him, the most important outcome of research investment is the impact of scientific breakthroughs on real people.

“We want to help make people as healthy as possible for as long as possible,” said Ward. “Without sustained investment in the infrastructure for translational research, we risk slowing down the advancements that could help us achieve healthier, more active longevity. This is a huge loss for all of us, not just scientists."

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.