By:

Published Date

Forecasting a Pandemic

Infectious disease modeler predicts how interventions limit spread of COVID-19 in San Diego, including as part of campus Return to Learn program

A student participates in the UC San Diego Return to Learn Program. Credit: Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

Natasha Martin’s heart stopped when she first saw a photo from Wuhan, China, depicting a huge hospital ward of patients on ventilators—all unable to breathe on their own due to an unusual pneumonia caused by a novel coronavirus.

“I suddenly realized the resources required to care for so many seriously ill patients could overwhelm our health systems too,” she said. “Then models came out predicting that inaction in the U.S. might result in more than 2 million deaths.

“I knew then that we needed to plan for the eventual impact of this coronavirus on San Diego, and that would require our own data, and our own models.”

Martin is an associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine and an infectious disease modeler. That means she develops mathematical models of the ways infectious diseases are transmitted, then uses the models to evaluate and predict the effects of various public health interventions and other variables. Most recently, she has applied her talents to tracking and forecasting potential COVID-19 transmission on campus, as leader of the UC San Diego Return to Learn Program.

Before COVID-19, Martin’s research had focused on modeling hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV transmission and prevention among high-risk groups, many of whom also face bias and stigma. It’s a job she loves because she gets to apply what she’s good at (math) toward understanding the world we live in, including human health, behavior and social justice. One of the things Martin is most proud of is a project in which she used data to forecast the benefits for entire communities if people with HCV who use drugs receive appropriate care. The work helped overcome resistance to dedicating public health resources to these individuals.

Then she saw that photo, and her work took a new turn.

In early March, she began developing models of how the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, now known as SARS-CoV-2, might spread in San Diego, inputting data specific to the region, such as number of people and hospitals, and updating it as public health recommendations, such as social distancing, were implemented.

Natasha Martin, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine and infectious disease modeler

With that, as well as several other publicly available models, Martin started forecasting the resources San Diego’s hospitals would need to address the pandemic, answering questions such as: How many patients will require hospitalization? How many ICU beds and ventilators will be needed? And how quickly?

Soon after, California’s shelter-in-place order went into effect. Not only was it a new data point for Martin’s models, it changed the way she worked. Like most other researchers, she started working from home, and with the new venue came a new difficulty. With no daycare available, Martin would also need to tend to her two small children, ages 3 and 5.

Martin says it’s been a challenge to share parenting duties with her husband, an infectious disease physician, and find time for numerous Zoom meetings with her team and collaborators during the day. Most nights around 8 o’clock, with the kids in bed, Martin makes an espresso and begins the second part of her day — running her models. (On a related note: if you’re a UC San Diego student with a background in math or engineering, get in touch — she may be able to use your help.)

Here’s what she’s finding in those wee hours: uncertainty, but also optimism.

“There was so much uncertainty because early on we only had Wuhan’s arc after their peak—and San Diego is different in a lot of ways, including the way we’ve responded with interventions, such as physical distancing and masking, and how quickly those were implemented.”

To validate each model and understand their differences, Martin first used past data to see how closely each element “predicted” what really happened.

She said San Diegans should feel good about the sacrifices they’ve made in terms of physical distancing and sheltering-in-place. According to her research, without those interventions, there could have been 6,000-18,000 total COVID-19 deaths in San Diego County by now; the current fatality count is 230.

“That’s good news, but the transmission rates we’re seeing—how many other people a single infected person subsequently infects—are still higher than we would have expected with these strict restrictions in place, and we worry what will happen when restrictions are relaxed,” she said.

“The problem with successful public health interventions is that people stop seeing the need for them.”

Amid the uncertainty, there are two main points that are clear and consistent across all models and all locations, Martin said: 1) Physical distancing has gone a long way toward reducing transmission and “flattening the curve”—preventing surges in people testing positive for COVID-19 that may overwhelm our health systems. 2) Once acceleration comes to a region, it comes swiftly, and hospitals need to plan accordingly.

While Martin was deep into helping UC San Diego Health and San Diego County prepare for what’s to come, infectious disease specialist Dr. Robert “Chip” Schooley, a professor in the Department of Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, called her up. He explained that he was working with a committee to explore scenarios for the UC San Diego campus in the fall, an effort that may include widespread testing for the virus. He asked Martin if modeling could help.

“I was excited to use modeling to understand how to detect outbreaks early and reduce campus transmission risk, using models tailored to UC San Diego—including campus housing configurations, classroom sizes, and, with Chip’s help, testing to tell us where the virus is, and isn’t,” Martin said.

That’s when the UC San Diego Return to Learn Program was born.

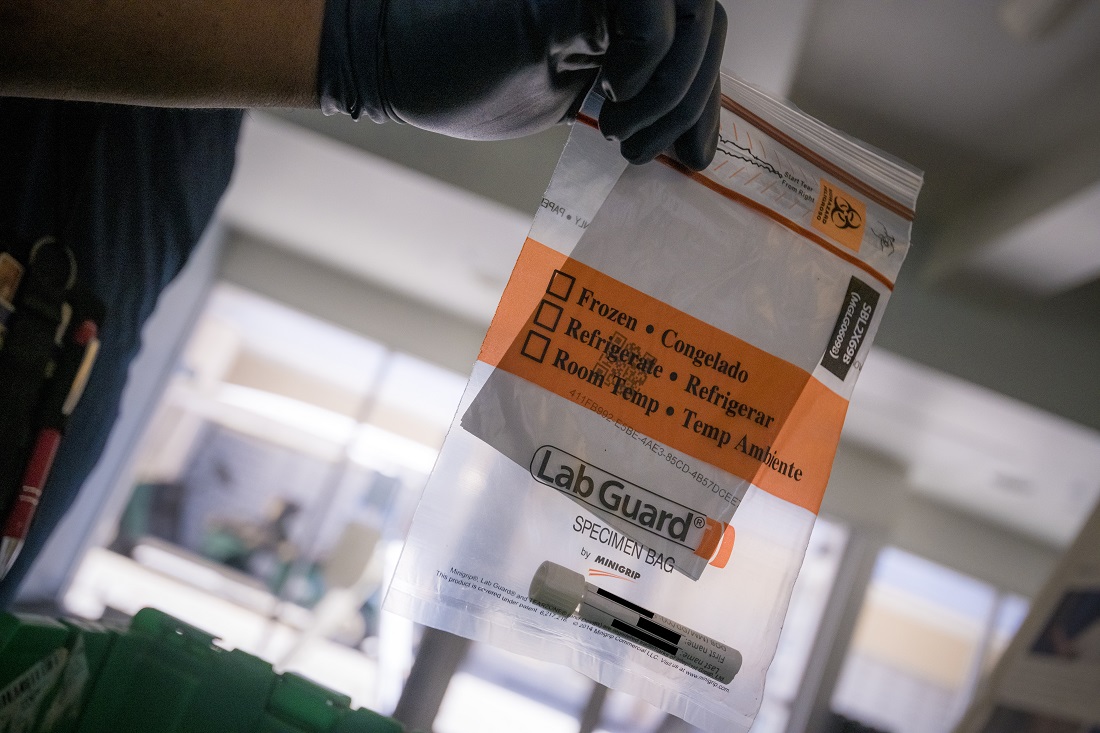

A student provides self-swab to be tested for presence of the novel coronavirus, as part of the UC San Diego Return to Learn Program.

Now in its initial phase, Return to Learn makes COVID-19 testing available to the roughly 5,000 students currently living on campus. It is an effort to track the novel coronavirus and better position the campus to resume in-person activities in the fall. If successful, the program could be expanded to the rest of the UC San Diego community in September.

Martin will use the program data to build models and run simulations that specifically reflect UC San Diego, its facilities, housing configurations and the way people move and interact around the campus. This knowledge may help university leaders better understand how to most effectively detect cases early, mitigate transmission risk and guide key decisions regarding housing, class sizes and classroom configurations.

Martin is happy to see so many students lining up to participate in Return to Learn. The program team is finding that students take pride in contributing to a greater good—helping make the UC San Diego campus as safe a place as possible to live, learn and work.

While sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, Martin has enjoyed spending time with family and gardening.

“I think we’re all looking forward to a time where we can resume in-person activities, and we want to take an evidence-based approach,” said Martin. “Our program will support data-driven decision making about how we can reduce risk on campus.”

As Martin herself continues to adhere to recommendations to stay at home, she’s surprised to find herself enjoying more aspects of it than she would have expected. She has more time to spend with her family, more time for gardening, going for walks and learning new things, such as how to build a surfboard rack.

"Fortunately, I can sometimes run my computer simulations while I teach my daughter subtraction,” Martin said. “And she is really excited that her mom’s work is helping us understand how to prevent the spread of the infection. I hope it’s an inspiration for her.

“This pandemic is forcing many people to reevaluate their priorities and think about new ways to work, and to organize and balance their lives—sometimes in ways that I hope will be long-lasting.”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.