By:

- Katherine Connor

Published Date

By:

- Katherine Connor

Share This:

The SonoHand team—Mayuki Sasagawa, Barry Cheung, Brandon Chung, and Simon Kim—with their prototype and project sponsor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine Simulation Training Center.

Creating an Engineering Senior Design Project….at Home

How students, faculty and staff transitioned the hands-on, team-based capstone engineering course to remote instruction

Curbside delivery of 3D-printed parts, the cooperation of roommates, weekend build sessions in Riverside and communication, communication, communication. This is what it took for graduating engineering students, staff and faculty at UC San Diego to transition the hands-on, team-based capstone mechanical engineering design course to remote instruction in the age of COVID-19.

“How do we get the student teams to make something that’s a functional prototype or better? This was the worry on my end, and I was very pessimistic in the beginning about whether or not we could achieve anything meaningful for the students,” said David Gillett, one of four instructors for the mechanical engineering capstone design course at the Jacobs School of Engineering. “The reality has proven amazingly positive. I am so impressed. These students are creative, resilient and adaptive.”

Normally, teams of four to five students spend 10 weeks creating a solution to a real-world problem put forth and sponsored by a local company or research lab. They meet regularly with each other, with their instructor and with their project sponsor to design and build a physical product that meets the sponsor’s needs. Students normally have access to a full machine shop, electronics shop, rapid prototyping tools, and advice from engineering staff. In past years, students have developed an elbow orthotic device to help a 5-year-old regain use of his arms; a neonatal simulation system for a complicated medical procedure; and a “mouse lickometer” to help scientists better study alcoholism.

What were students and staff to do when, a mere week before spring quarter, the state of California was put under shelter in place restrictions, most students moved off campus, and students and staff weren’t able to access the campus design studio, maker space, and tools that they would normally take advantage of to build their projects?

“As instructors, we briefly considered switching to a paper exercise, but we decided that student motivation was the most important factor,” said Nathan Delson, another of the course instructors. “The students had already started learning about their projects in November and were motivated to solve real-world problems for their sponsors.”

Students designed and built a prototype of a robotic brusher that will be used to study nerve fibers called C-tactile afferents.

“We had these long conversations and decided that the best decision was to try and get the students to access outside resources to actually make things,” said Gillett. “I have to give huge props to the engineering staff because we had a number of staff individuals that took 3D printers home and became a service bureau, printing parts for students in a day or two.”

For the students, it was all about getting creative. One team resorted to the kindness of an uninvolved roommate in order to manufacture their automatic brushing device, sponsored by a professor at the UC San Diego Department of Anesthesiology who studies the sensations of pleasure and plain derived from stimulating C-tactile fibers.

“I got a 3D printer last quarter as a Black Friday sale purchase, and that turned out to be really helpful,” said mechanical engineering student Andrew Ma. “Most of the quarter, my teammates were in San Diego and I was at home in the Bay Area. So, it was complicated because I was sending our design files to my roommate and having him print the stuff. Then he would leave them outside, and someone from our team would come over and pick up the 3D-printed parts from the doorstep.”

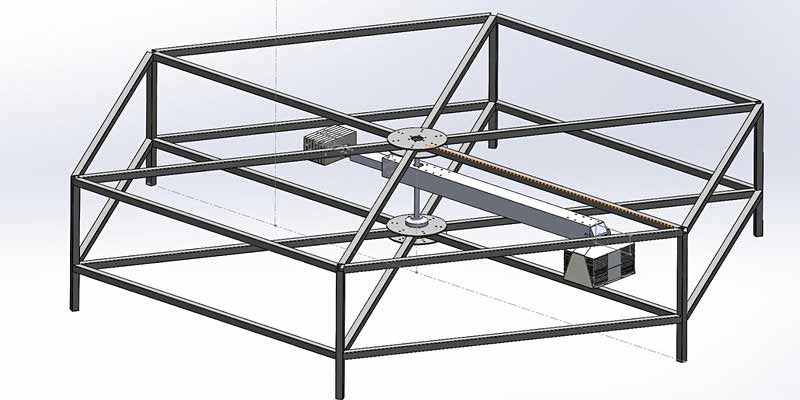

The SonoHand is a robotic arm meant to hold ultrasound probes of different sizes in a precise location on a patient during a procedure.

Another project, team SonoHand, was tasked with developing a robotic arm that doctors could use to hold an ultrasound probe in place on a patient during a procedure. The students were spread out around the San Diego and Riverside areas, and in order to develop a prototype, used the manufacturing facility of one team member’s family company on the weekends.

“Throughout the week, we all helped design and do Functional Data Analysis,” said team member Simon Kim. “On weekends, we’d come together, meet up in Riverside, and build it together. We wanted to make something physical out of this project; that was the main goal,” said Kim.

This put extra pressure on the team during the week, ensuring that the components they’d be building would work, and scheduling their design and build sessions with these couple of weekend marathons in mind.

With their expected manufacturing sites and tools no longer accessible, students turned to purchasing more off-the-shelf components for their projects, which added a challenge to staying within the budget set by their sponsor, and accounting for COVID-related shipping delays for these parts.

“I think the biggest challenge, but also kind of a good way of thinking, is this innovative way of thinking that if there are problems that persist, there’s always a way to work around it,” Kim said. “You don’t have to rely on one methodology of thinking.”

There were some teams that, due to location, size or other constraints, weren’t able to build physical prototypes. Instead, they conducted thorough simulations and analysis to ensure their designs would work, and developed manuals detailing the sourcing, manufacturing and assembly of their product.

A rendering of the 13-foot centrifuge students designed to study the effect of a rocket launch on brain organoids being sent to space.

One team of students, sponsored by the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination and Space Tango, was tasked with designing a way for researchers to study the effects of a rocket launch on brain organoids being sent to the International Space Station.

“They’re performing research on the effect of low gravity on neurological development, so they’re sending these little brains up to the Space Station to see how gravity affects them,” said team member Nicholas Blischak. “As a result of having to send something to the Space Station you have to put it on a rocket, and they really want to see what the effects of that acceleration that the experiments are going to experience in the process of being sent into space are. Our project was to come up with a way to simulate that acceleration.”

To accomplish this, the team decided to design a 13-foot centrifuge that will mimic the acceleration and movement the brain organoids will experience on the Falcon 9 rocket. It will also be used as a control here on Earth to compare against the organoids in space.

This was too large of a product to build from home, so the team resorted to putting together a detailed blueprint of how exactly to build it.

“We’ve been told that our sponsor is going to manufacture it after we complete our designs, and work on it over the summer,” said team member Clara Blatchley. “So, it will be built this year, most likely.”

At the end of the quarter, the student teams all participated in a virtual poster presentation as part of a Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Senior Project Day. Judges from the engineering community and guests stopped be each team’s Zoom room for short presentations and Q&A.

While the students and staff were successful in finding ways to make this hands-on course a reality from afar, they’re hoping they can resume in-person meetings and use the Jacobs School of Engineering machine and prototyping lab resources again soon.

“I have an engineer brain that says I need to touch it, I want to feel it, can the device do this,” said Gillett. “And you just can’t do that remotely.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.