Bionic Hand Sparks Resilience in Patient After Electrocution Accident

Rehabilitation and prosthesis training at UC San Diego Health invigorate patient’s recovery

Media contact:

Published Date

Media contact:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

Christian Arreola simply wanted to catch a glimpse of the ocean from the top of his parents’ roof before sunset.

But as he carefully climbed up the wet rafters and crossed beneath an electrical wire overhead, the unimaginable happened — an arc of electric current knocked him to the ground and sent more than 13,000 volts of electricity surging through his body.

“I heard a zooming sound running through my entire body and my muscles were twitching and flexing out of control. It was so painful,” said Arreola, remembering those last terrifying moments before he was knocked unconscious.

Electric arcing can result from various factors, including faulty or deteriorated wiring and loose connections. If an exposed wire makes contact with water, an electric arc can occur. When Arreola stepped beneath the overhead wires on the wet surface, he unknowingly became a conduit.

The energy raged through his body, burning 50% of his chest, back, legs and right arm. From his parents’ home in Rosarito, Mexico, he was taken by ambulance to the US/Mexico border, where he was then transferred to a local ambulance that rushed him to the Regional Burn Center at Hillcrest Medical Center at UC San Diego Health.

Once at Hillcrest Medical Center, his trauma and pain were so severe that doctors recommended a medically induced coma.

“I don’t remember anything about being transported to the hospital, until I signed the paperwork to be put into the coma,” said Arreola, who lives in San Ysidro. “When you get electrocuted, it doesn’t just burn the outside of your body, but also the inside — my kidneys were also severely burned.”

When he awoke from the coma five days later, on March 31, 2022, he learned his right arm and hand needed to be amputated.

An electrical accident burned 50% of Christian Arreola’s chest, back, legs and right arm. He spent one month in the intensive care unit at Hillcrest Medical Center, followed by another three months in the Regional Burn Center at UC San Diego Health. Photo courtesy of Christian Arreola.

“And I said, ‘just go for it,’ because when I went into the coma, I honestly didn’t know if I was ever going to wake up again,” remembers Arreola, who was just 23 years old at the time.

Through adversity comes hope

Arreola’s recovery journey was lengthy, with one month spent in the intensive care unit at Hillcrest Medical Center, followed by another three months in the Regional Burn Center. In all, he underwent 20 surgeries for burns and an amputation during his time in the hospital.

Surgeons initially thought they’d need to amputate all the way to the shoulder, due to his severely burned muscle tissue. But Katharine Hinchcliff, MD, assistant professor of surgery at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and hand surgeon at UC San Diego Health, worked to salvage as much of the limb as possible.

“I had signed the paperwork to amputate all the way to my shoulder, but each time I’d wake up from surgery, Dr. Hinchcliff said she had removed some of the tissue but wanted to give the remaining tissue more time — and that’s what saved a lot of my arm. I’m so grateful to her for saving as much as she could.”

Hinchcliff explained to Arreola that the more of his arm remained, the easier it would be for him to eventually manipulate a prosthetic hand effectively.

“Trauma amputation surgeries are sometimes thought of as an acute, damage control surgery — and in some ways they are — but they must always be done with the end goal of function in mind,” Hinchcliff said. “Saving Christian’s elbow was so important because that would make his limb much more functional in the future, and his prosthetic adoption higher. It is definitely worth the additional surgeries and reconstruction to give it a shot.”

Near the end of his stay as an inpatient, Arreola met Jennie McGillicuddy, an occupational therapist in physical rehabilitation at UC San Diego Health. She visited him at his bedside in the Regional Burn Center to provide insight about upcoming long-term outpatient therapy work and to share possibilities for a future prosthesis. For the first time since the accident, hope surged through his body.

“To have something so tragic happen at such a young age, it was amazing to see that Christian was so eager to focus on what he could do to push himself forward and heal,” McGillicuddy said. “My initial goal is to never overwhelm a patient with too much information, but instead to help set them up for success as an outpatient in rehabilitation therapy and eventually learn to use a prosthetic. The sooner you can tie therapy work to meaningful activities, the more the patient is going to be motivated.”

McGillicuddy remembers helping Arreola out of bed as an inpatient and working with him on arm, shoulder and elbow stretches in different planes of motion. Early rehabilitation is crucial to prevent atrophy, and to strengthen the remaining arm muscles that will ultimately power a prosthetic.

“Jennie helped motivate me in more ways than she will ever know, and she expanded that resilience in me to figure out what I can do moving forward,” Arreola said.

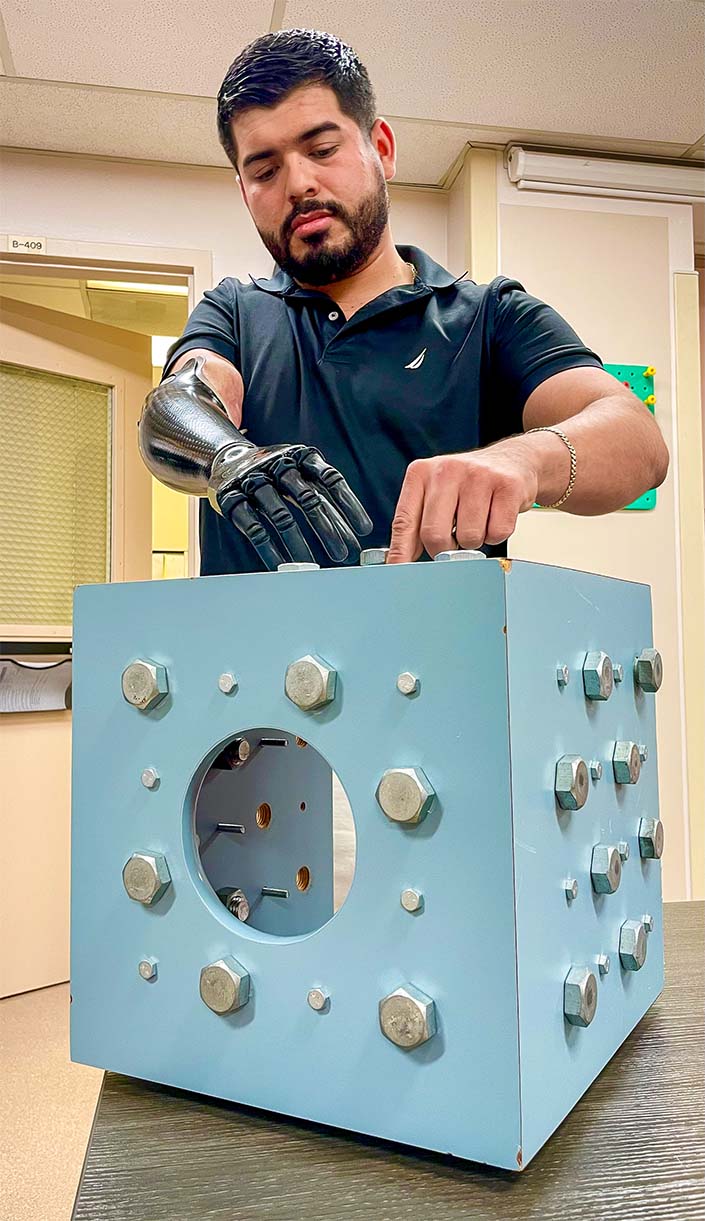

Christian Arreola tests his prosthetic hand skills by screwing bolts into a box at the rehabilitation gym at Hillcrest Medical Center at UC San Diego Health. Photo by Annie Pierce, UC San Diego Health

After Arreola’s hand and arm amputation and three months as an inpatient, he was released and began weekly outpatient rehabilitation treatment with McGillicuddy for more than a year. His amputation would take another three months to heal before he could be fitted for a prosthetic, so they began with pre-prosthethis training that would help prepare his muscles, joints and tendons in advance, McGillicuddy said.

“I was eager to get back out there, and I definitely did too much once I got home,” Arreola remembers, adding that he returned to the burn center every two days for wound care. “There were suddenly just so many things I wanted to do — especially the little things in life that before I didn’t take advantage of enough — like going to the ocean, which is just minutes away.”

“When I was in the hospital, I just wished I was at the beach, and I could feel the sand and the water. Now I go at least once a week. You learn very quickly to stop taking things for granted. I tell people all the time now, use your time off, use your freedom — you don’t want to look back and wish you’d done things differently,” he said.

Shaking hands with the future

On a recent day at Hillcrest Medical Center, McGillicuddy and Arreola met up to test his skills and reflect on how far he’s progressed with his prosthetic arm and hand. McGillicuddy shared that her favorite moment, when working with a patient who has a prosthetic hand, is when they have the trust in themselves to shake her hand without crushing it.

Instantaneously, and with a sly grin, Christian extended his bionic, carbon fiber arm, grabbed her hand with the myoelectric fingers of his prosthetic hand, and shook away.

“See, it makes me cry every time,” McGillicuddy said, smiling through tears.

Arreola’s myoelectric prosthesis uses the electrical signals generated by his muscles to control its movements. Electrodes embedded in the prosthesis socket detect electrical activity in the residual limb. The electrodes amplify the signals, which are then processed by a microchip to drive the movement of the prosthesis.

“The first time I put the prosthesis on, I was like, ‘Does this even work?’” Arreola said. “It can be challenging at first, because you’re not used to having to figure out how to use an arm and a hand that aren’t part of yourself.”

But Arreola was up for the challenge, choosing a myoelectric hand from Psyonic, a San Diego-based company that invented the first multi-touch sensing bionic hand on the prosthetic market.

The prosthetic hand allows him to choose from multiple grips on an app from his phone. He programs his most frequently used movements from the app, which are then powered by specific arm muscles he has worked with McGillicuddy to define and strengthen. He’s gotten so proficient with the use of his bionic hand that he regularly tests new prototypes for Psyonic and demonstrated the prosthetic’s capabilities at this year’s Comic-Con event in San Diego.

“I didn’t want a prosthesis that would just cover up something I didn’t have,” Arreola said, explaining he was not interested in a silicone passive hand. “I wanted a robotic hand that could do the functional things I could no longer do — plus, I have to say, it looks pretty cool.”

A year of working with McGillicuddy weekly has trained his muscles to send the right messages to the prosthetic hand, based on the task he wants the hand to do. When he began outpatient treatment, McGillicuddy asked him to choose four goals to prioritize, which included picking up a water bottle, carrying an iPad, tying his shoes and shaking someone’s hand.

“Christian has had a wonderful attitude all through therapy. Just look at the skills he has now — it’s amazing,” McGillicuddy explained from the rehabilitation gym at Hillcrest Medical Center where the two met weekly for a year. “My passion is to inspire hope in patients, and Christian is an incredible example of hope and resilience.”

Later this year, outpatient therapy like Arreola’s will transition to the new McGrath Outpatient Pavilion, which is currently taking shape at UC San Diego Health’s Hillcrest Medical Center campus. The 6-floor, 250,000-square-foot outpatient pavilion will house specialty clinical programs and outpatient services including rehabilitation therapy.

Affliction fuels competition

Arreola discovered he was motivated by more than just regaining functional hand skills after his amputation and set his sights on CrossFit competitions just five months after the devastating accident. He said he had gained approximately 30 pounds after losing his arm and realized that being fit could help boost his independence.

“Before the accident, I didn’t exercise, and now I’m doing things I could never do before, like weightlifting,” he said. “I can now lift 150 pounds with one arm. It’s been a push to see what I can do, and I like the challenge.”

Arreola currently competes in local competitions without his prosthesis, but is aiming to compete in an adaptive competition, which features specific class categories for prosthetics, in Texas in September, 2025.

“My goal is to win the upper extremity amputee class,” Arreola said while demonstrating his skills of placing pegs into a box at the rehabilitation gym. That instantly prompted a high-five from McGillicuddy.

These days, Arreola routinely visits the Regional Burn Center to share his story with patients who have found themselves at the beginning of their rehabilitation journey.

“I want to help motivate them during their darkest days because you have to trust the process. I’ve had so much support from every nurse, therapist and doctor at UC San Diego Health who has helped me get through all of this. I want people to see what is possible and give them hope about their future.”

Regularly competing in CrossFit competitions has given Christian Arreola motivation to see how far he can push himself physically. He hopes to win the ‘upper extremity amputee class’ division at an upcoming adaptive CrossFit competition in Texas. Photo courtesy of Christian Arreola

You May Also Like

UC San Diego is Strengthening U.S. Semiconductor Innovation and Workforce Development

Technology & EngineeringStay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.