Award-Winning Film Reanimates Queer Culture of 1970s South Korea

Story by:

Published Date

Story by:

Topics covered:

Share This:

Article Content

Fifty years ago in Seoul, South Korea, there was a vibrant queer hub located in the Euljiro neighborhood where theaters and bars served as popular sites for same-sex encounters. In 2020, Associate Professor of History Todd A. Henry returned to the area to search for remnants that would offer clues about the evolution of gay subculture from the 1950s until the 1980s.

A turning point came when he and two architectural historians discovered the shuttered Bada Building, which was built in 1969 and once held a theater and cabaret on the top floors. The site sparked a story for a documentary film titled “Paradise,” researched and produced by Henry in collaboration with film director Hong Minki. The work documents South Korea’s vibrant gay urban life, following the joy and pain of six elderly men whose stories appear for the first time through historical animation.

The film recently won the grand prize in documentary at the 27th Annual Korean Urban Film Festival, led by the University of Seoul. We caught up with Henry to learn more about how the film originated, the ways mass media unintentionally strengthened gay communities in South Korea, details on his next film project and much more.

Q. Your film has served as a catalyst to connect gay community members across generations in Korea. How did this idea emerge?

Henry: One of the inspirations for the film was a series of events that took place at UC San Diego's LGBT Resource Center called “Intergenerational Dialogues.” I'm a gay man who came of age in the era of HIV/AIDS (1990s), although I wasn't of the generation that lost a lot of friends and relatives; I had always felt that my generation didn't quite understand that traumatic period. It was helpful to hear the concerns of my elders and the students I teach, as well as the different perspectives of staff.

When I pitched my idea for “Paradise” to my filmmaker friend, Hong Minki, it became apparent that this would be an opportunity to start an intergenerational dialogue among queer communities in South Korea. Hong is in his mid-thirties, I’m 52 and I interviewed men in their 70s and 80s for the film—we also had Vogue dancers in their 20’s perform at the opening screening. The film not only offers a chance to revisit history, but it also brings together people of different ages, genders and sexual identities to create dialogue across generations. I believe that listening to each other’s stories can inspire new possibilities of empowerment.

Q. Each of the men you interviewed were animated into the film as memorabilia from the theater. What motivated this creative choice?

Henry: I interviewed about 10 people for the film, but none were willing to appear on screen for privacy reasons. We had footage of the Bada Theater, one of the popular gay theaters of the 1970s and 1980s that had closed in 2010. I asked the interviewees if we could use their modified voices in the film, and Hong proposed that we animate the film. The image that first popped up for me was Disney, but then I quickly realized he was talking about a kind of historical animation!

When I first started going to South Korea in the 1990s, I often saw groups of men standing outside restaurants or bars having a smoke together, and then going back in and drinking together. We decided to personify the people whose physical bodies we could not capture on screen through these memorabilia that were significant during that area—alcohol, cigarettes, matchboxes, bottle caps and more. These were superimposed over the footage of the theater to demonstrate how gay people inhabited the space of second-run movie theaters where they could buy an inexpensive ticket and linger as long as they wanted.

Q. In your film and forthcoming book, you explore how queer people in Korea built community by finding spaces where gay people gathered, highlighted in the mass media (albeit in a derogatory way). Tell us more about what you describe as ‘shadow reading.’

Henry: During this time in South Korea, mass media unintentionally helped individuals fashion new kinds of identities, foster new relationships and explore new economic opportunities. Prior to the 1990s, journalists were active participants in promoting homophobia and transphobia. Yet for older gay men I interviewed for “Paradise,” these stories became guides to find one another—it was a lifeline for them. They would read it, ignoring the fact that they were being criticized for wanting to meet another man and, instead, went straight to the places described.

In the book I’m finalizing, ‘Profits of Queerness: Media, Medicine and Citizenship in Authoritarian South Korea, 1950-1980” (University of Hawai’i Press), I call this “shadow reading.” At the time, queer people lived in the shadows, barely allowed to speak for themselves. Most often, powerful outsiders spoke for them: journalists in the mass media, doctors in medical reports and police officers in legal records. But reading these same materials also allowed queer people to imagine themselves as a community, to find one another.

This intersection of mass media, sexual medicine and state policing shaped cultural norms in South Korea, defining such categories as “men” and “women,” “healthy” and “unhealthy.” Queer and intersex citizens transformed pejorative representations, pathological diagnoses and homophobic rulings into means of self-empowerment on the fringes of an illiberal polity. In this way, I show how “queerphobia” and “queerphilia” intersected as central dynamics of South Korean modernity.

Q. Researching and producing “Paradise” in collaboration with director Hong Minki was your first foray into filmmaking. What did you learn about adapting your work to this medium?

Henry: I’ve always been interested in film. I teach a class at UC San Diego called “Modern Korean History through Film,” and I've found that my students perk up and make really brilliant connections between what they read and what they see on screen. Making “Paradise” was my first opportunity to not just sit back as a consumer of film, or an analyst, but actually participate in the process of filmmaking. It's a really effective way to communicate with people about history.

I learned a lot along the way. At first, I felt compelled to give the audience a lot of background information, as you would in a footnote. Academic articles are often framed to appeal to other scholars; sometimes, we become too indulgent in theoretical discussions or impenetrable prose. But Hong always reminded me that we should tell a visual story, and that some historical details needed to be left out. I was inspired by the process and feel grateful to have worked with Hong and his artistic team to make my vision of the past an artistic reality.

Q. You enjoyed this experience so much that you’ve decided to make your own film. Tell us more about your next story, featuring a pioneering Korean fashion designer.

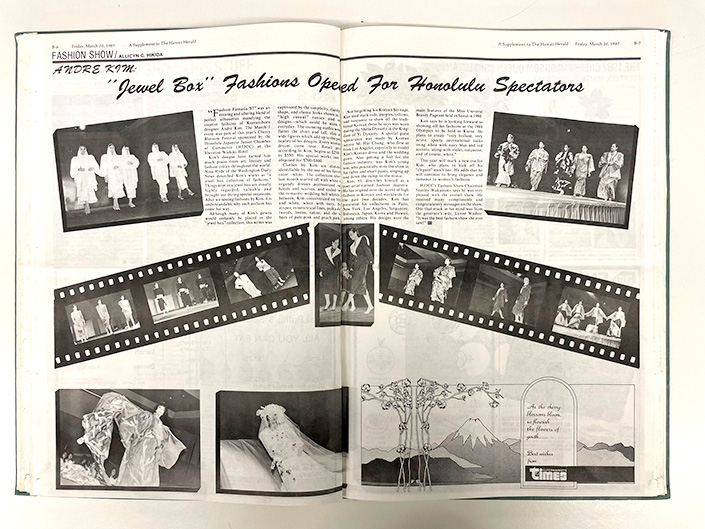

Henry: In fall 2023, I received a fellowship from the Suraj Israni Center for Cinematic Arts in the School of Arts and Humanities to launch a new film that I’m hoping to direct about South Korea’s first male fashion designer, Andre Kim (1935-2010). The story will center on how, at a time when few of his countrymen could go overseas, Kim traveled the globe, and how local communities that he visited organized extravagant fashion shows, particularly in Hawai’i. These events, which began in the early 1970s, were unforgettable spectacles, fundraising opportunities and a way for communities to bond. Many people living in Hawai’i had ethnic or ancestral ties to Korea, Japan and other parts of the Pacific Rim; to meet an Asian designer of high fashion was really meaningful to them.

I will be returning to Hawai’i in December to do some follow-up interviews. I have recently connected with Honolulu’s Japanese American community, which invited Kim to their cherry blossom festival several times during the 1980s. It’s an interesting way to explore the relation between Japan and Korea and the globalization of Korean culture that we see today in K-Pop.

You May Also Like

Engineers Take a Closer Look at How a Plant Virus Primes the Immune System to Fight Cancer

Technology & EngineeringStay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.