By:

- Erika Johnson

Published Date

By:

- Erika Johnson

Share This:

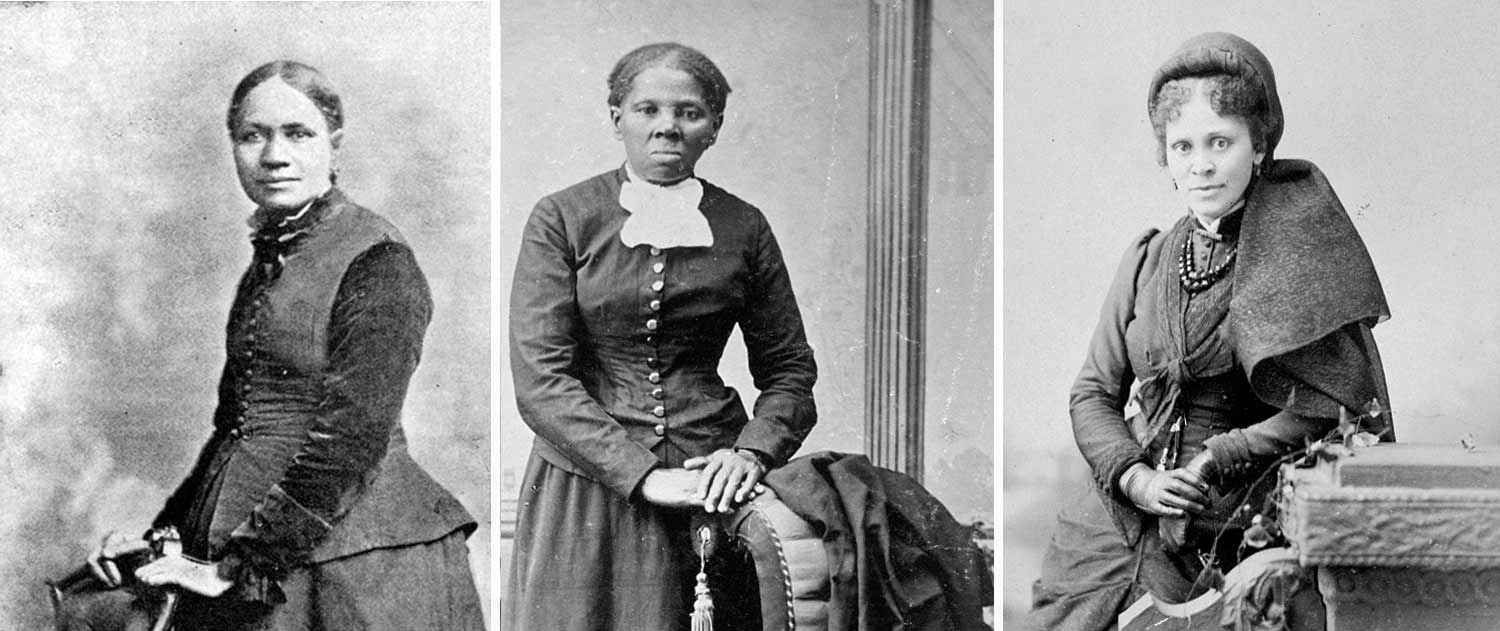

The passage of the 19th Amendment would not have been possible without the contributions of suffragists Frances E.W. Harper, Harriet Tubman and Hallie Quinn Brown, and many other black women who propelled the movement to achieve voting rights for all women and men in the U.S. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.

An Incomplete Victory

Passage of 19th Amendment did not benefit black women

Women do not have the intellectual and emotional capacity to handle the responsibility of voting. The mental energy would be too draining and jeopardize reproductive health. And if women do not have the physical capacity to defend the United States, they should have no involvement in determining its policies.

These were the widely accepted (and completely false) beliefs that permeated the ideology of the United States in the middle of the 19th century as women across the nation began to mobilize and demand their right as citizens to vote. It took eight decades and three generations of women to convince Congress to pass the 19th Amendment in June 1919 and implement the law in August 1920.

But as we celebrate the centennial of the historic achievement, it is important to remember that not all women benefitted. It would take another 45 years and the passage of the Voting Rights Act before black women became truly enfranchised. Despite the significant contributions of black women in making the 19th Amendment a reality, their role is often unsung.

“We often think about the heroes of the women’s suffrage movement as being people like Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but we forget or pay less attention to some of the equally important women of color leaders like Sojourner Truth, a former slave, educator Mary Church Terrell or journalist Ida B. Wells,” explained Sara Clarke Kaplan, an associate professor of Ethnic Studies and director of Critical Gender Studies at UC San Diego.

She continued, “These are people who fought every step of the way, marched at every rally—even when they were told they had to march at the back—created their own organizations and continued to fight for universal suffrage after being denied twice.”

Kaplan is a scholar of historical and contemporary black feminist thought. She co-leads the UC San Diego Black Studies Project with Dayo Gore, chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies.

Bridges burned

After the Civil War, what began as a united front to achieve voting rights for all citizens in the U.S. eventually diverged into separate campaigns for black men’s suffrage versus white women’s suffrage. Although they attempted to join and participate in both, black women were often excluded from white women’s organizations and activities. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was created in 1890, and the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) launched in 1896.

“The passage of the 19th Amendment took longer because white women suffragists refused to work in solidarity with black women suffragists, alienating and treating them as second class citizens,” said Kaplan. “It was a set of race and gender-based political struggles that were at times collaborative and at times in huge conflict around this question of who has access to rights of full citizenship.”

Mary Church Terrell, a teacher and civil rights activist, helped launch the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and led the organization for the next four years, with a goal of attaining women’s suffrage and achieving civil rights for all black women and men. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The passage of the 19th Amendment was closely intertwined with the enforcement of the 15th Amendment, which was passed in 1870 to prohibit discrimination at the polls based on a citizen’s “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, black men remained disenfranchised as Southern states instituted high poll taxes, literacy tests, violent intimidation and other means of excluding them from exercising their vote. When the 19th Amendment was proposed, U.S. Senators were in opposition because they feared it would require the 15th Amendment to be enforced.

Kaplan explained that whereas white suffragists focused primarily on achieving gender equity, black suffragists were driven to improve civil rights for all people—including gender, race and class equity. At a NAWSA convention on Feb. 10, 1900, black suffragist Mary Church Terrell spoke about the unfairness of some inheriting voting rights simply because of their gender or race.

“The elective franchise is withheld from one half of its citizens, many of whom are intelligent, cultured and virtuous, while it is unstintingly bestowed upon the other, some of whom are illiterate, debauched and vicious, because the word ‘people,’ by an unparalleled exhibition of lexicographical acrobatics, has been turned and twisted to mean all who were shrewd and wise enough to have themselves born boys instead of girls, or who took the trouble to be born white instead of black,” said Terrell, as quoted in the Washington Post.

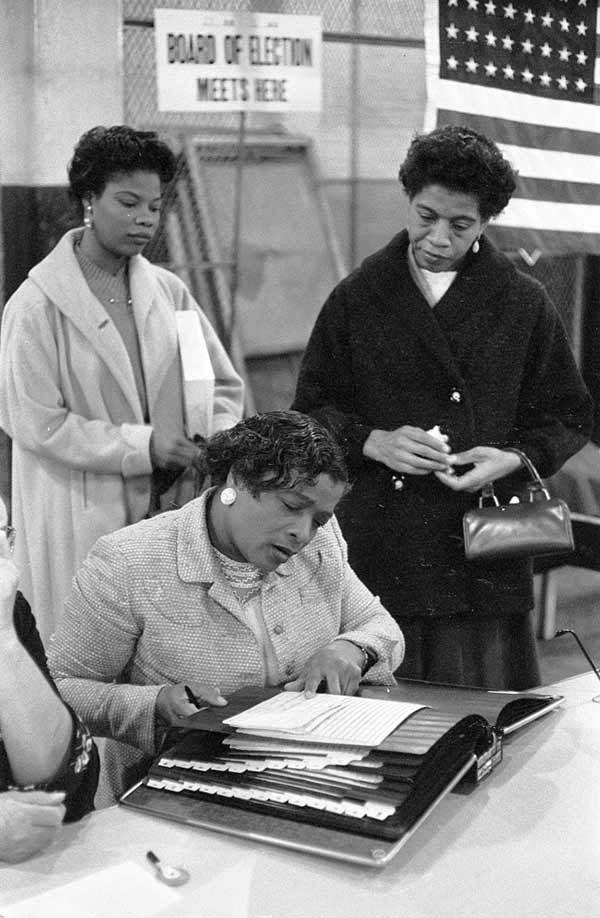

Unfinished work

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” The 19th Amendment became law in 1920, yet almost immediately, barriers were enacted in the South to prevent black women from taking part in elections. Kaplan explained that it was not until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 that both black men and women were afforded access to the polls. In 1975, an Amendment was added to prohibit discrimination against language minority citizens, extending overdue voting accessibility to Native, Latinx and other diverse populations.

Although the 19th Amendment became law in 1920, it was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that many black women—as well as black men—could access the polls without barriers. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Third-year UC San Diego student Mihiri Kotikawatta, although proud of the progress that movements have made, believes the U.S. still has room to improve. A political science and global health major, she serves as the Social Justice Peer Educator Community Liaison at the campus Women’s Center. “In some states, policies such as restrictive voter ID laws remain that make access to voting difficult, especially for lower socio-economic communities of color,” she said.

Kaplan echoed that there continue to be issues surrounding gerrymandering, or drawing electoral district boundaries based on party lines or valuable voter populations. Voting obstacles remain, from polls closing early to requiring drivers licenses. Kaplan explained that these requirements disproportionately affect women of color, who have the lowest income and often have less flexible work hours.

Ultimately, Kotikawatta has a positive outlook about the future. “I do feel that this generation of women is doing a phenomenal job of advocating for equity and inclusion. Seeing incredible female leaders such as Congresswomen Rashida Tlaib, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar and many others in my community, I believe that a lot of intersectional issues women face are finally coming to light and are being discussed.”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.