Economists Price BP Oil Spill Damage to Natural Resources at $17.2 Billion

Study published in Science improves valuation techniques that drive policy decisions

Published Date

By:

- Inga Kiderra

Share This:

Article Content

Oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill approaches the coast of Mobile, Ala., May 6, 2010. CREDIT: U.S. Navy

The BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico was the largest maritime oil spill in U.S. history. Almost seven years to the day after the start of the environmental disaster, researchers have published a price tag of the damage done to natural resources: $17.2 billion.

The paper, in the April 21, 2017 issue of Science, puts a monetary value on injuries to natural assets that don’t have a market price, caused by the April 20, 2010 accident on the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling platform. Before the blowout on the well was capped in August of that year, it released 134 million gallons of oil into the ocean, polluting the water, soiling beaches and marshes, and killing marine life.

Richard Carson

Environmental economist Richard Carson of the University of California San Diego was one of the principal investigators on the valuation study.

“This is the biggest research project ever done in environmental economics and defines the state-of-the-art for valuating ecosystem services,” said Carson, a professor and former chair of the Department of Economics in the UC San Diego Division of Social Sciences.

The study was undertaken on behalf of state and federal trustees of the Gulf’s natural resources and conducted under the guidance of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It was initiated in May 2010 and ran concurrently with assessments by natural scientists. Estimates from the valuation study, Carson said, were available in advance of the settlement reached out of court in 2016.

The Science paper and the paper’s supplementary materials are a summary of more detailed materials prepared for NOAA over the course of about five years of research, Carson said. The data collected as part of this work is also online.

The study’s $17.2 billion estimate is based on a nationally representative stated preference survey, assessing people’s willingness to pay a one-time tax to prevent the effects of the 2010 BP oil spill from occurring in the future.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 3,656 randomly selected adults. An additional 1,492 individuals, who were not interviewed in person, were surveyed by mail and phone to make sure they didn’t differ substantially from the respondents on whom the estimates are based.

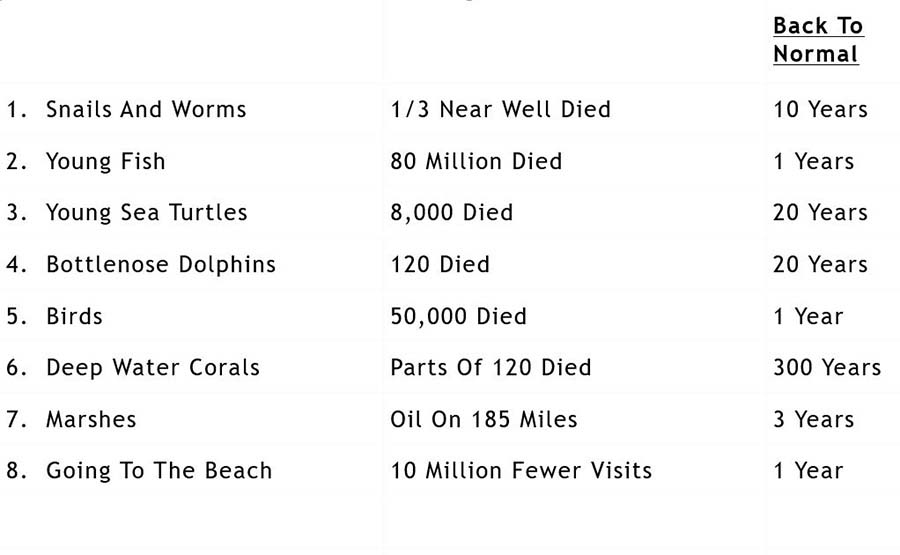

People responding to the survey were given this information on injuries to natural resources in the Gulf and how long it would take for them to recover. CREDIT: Courtesy Richard Carson

The in-person questionnaire included descriptions of the Gulf’s natural resources before 2010, injuries to the Gulf as a result of the oil spill, a proposed program for preventing a similar accident in the future, and how much the person’s household would pay in extra taxes if the program were implemented.

People were randomly assigned to consider either a smaller or larger set of injuries to natural resources. The smaller set included “the number of miles of oiled marshes, of dead birds and of lost recreation trips.” The larger set included those in the smaller set, “plus injuries to bottlenose dolphins, deep-water corals, snails, young fish and young sea turtles.” People were also randomly assigned different tax amounts for the prevention program. They voted for or against the program at a specific tax amount that they would pay.

The researchers estimate, conservatively, that the average household is willing to pay a $153 one-time tax to prevent the larger set of injuries. The figure of $17.2 billion is derived from multiplying $153 by the number of U.S. households represented.

Carson said he hopes that the prevention program described in the survey will eventually be implemented. After the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, Carson served as a principal investigator on economic damage assessments for the State of Alaska. The plan put into place after that survey, he said, has now prevented several subsequent spills.

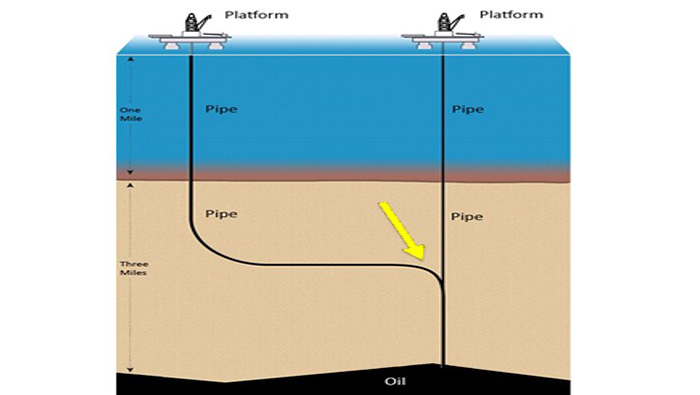

The survey’s proposed prevention plan suggests drilling a relief well at the same time as the original well. In 2010, starting from scratch, it took three months to cap the flow of oil into the ocean. A predrilled well could cap it in a matter of days. CREDIT: Courtesy Richard Carson

Stopping a well blowout like the one in the BP oil spill incident involves drilling a relief well to intersect the original well and pumping in concrete at very high pressure, Carson said. The survey’s proposed prevention plan suggests drilling a relief well at the same time as the original well. In 2010, starting from scratch, it took three months to cap the flow of oil into the ocean. A predrilled well could cap it in a matter of days.

The Science study not only puts a dollar figure on the natural-resource damage from the BP oil spill, Carson said, it also solves a number of technical challenges in valuations that drive policy and will help policymakers.

A worker cleans up oily waste on Elmer's Island just west of Grand Isle, La., May 21, 2010. CREDIT: U.S. Coast Guard

“Effective policy decisions frequently require knowing the implicit economic value that people place on goods and services not normally bought and sold in the marketplace. These range from the value of time spent in traffic congestion and security lines to the value of providing outdoor recreation opportunities or reducing risks from exposure to toxic chemicals,” Carson said. “This study made major advances in developing techniques for measuring these values, including improved ways of presenting information about complex ecosystems to people, and enhancing the statistical reliability of estimating people’s willingness to pay for nonmarket goods and services.”

The full list of authors is, alphabetically: Richard C. Bishop, University of Wisconsin; Kevin J. Boyle, Virginia Tech; Richard T. Carson, UC San Diego; David Chapman, U.S. Forest Service; W. Michael Hanemann, Arizona State University; Barbara Kanninen, BK Econometrics; Raymond J. Kopp, Resources for the Future; Jon Krosnick, Stanford University; John List, University of Chicago; Norman Meade, NOAA; Robert Paterson, Industrial Economics, Inc.; Stanley Presser, University of Maryland; V. Kerry Smith, Arizona State University; Roger Tourangeau, Westat; Michael Welsh, independent consultant; and Jeffrey M. Wooldridge, Michigan State University. Providing research support were Matthew De Bell of Stanford, Colleen Donovan of Abt Associates, Matthew Konopka of Prospect Analytics and independent consultant Nora Scherer.

To learn more about efforts to restore natural resources in the Gulf: NOAA Gulf Spill Restoration.

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.