UC San Diego Hosts Inaugural Coalition on Drug Shortages

The Bio-5 Coalition is a new White House initiative to address the global crisis of drug shortages; UC San Diego hosted the launch of the international summit.

Published Date

Article Content

In early May, University of California San Diego Chancellor Pradeep Khosla received an inquiring phone call from Tarun Chhabra, senior director for technology and national security for the Biden Administration’s National Security Council.

The question: Could UC San Diego, as a premier research university located in one of the biggest biotech hubs in the country, help host the first meeting of an international coalition aimed at addressing the growing crisis of drug shortages around the world?

Chancellor Khosla suggested the White House partner with UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences to make this meeting a reality. One month later, thanks to the combined efforts of the pharmacy school and Jacobs School of Engineering, the Bio-5 Coalition met for the first time at UC San Diego’s Park and Market building. The day started with opening remarks from Pharmacy School Dean Brookie Best, Pharm.D., and ended with a tour of two labs at the Jacobs School that are on the cutting edge of biomanufacturing, which leverages living systems to manufacture biomedical products.

“At UC San Diego, we are committed to improving patient care through innovative research, education and collaboration,” said Khosla. “Our world-renowned faculty, physicians and researchers are at the forefront of addressing the worldwide crisis of drug shortages, and we are proud to partner with the White House and international leaders to drive solutions to advance global public health.”

From left to right: UC San Diego attendees of the Park and Market meeting included Brookie Best, dean of Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, who provided opening remarks; Albert Pisano, dean of Jacobs School of Engineering; John Carethers, Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences, and Corinne Peek-Asa, Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation.

A one-of-a-kind summit

Coinciding with the 2024 BIO International Convention that took place in downtown San Diego in early June, the Bio-5 meeting brought together pharmaceutical industry leaders and government representatives from the United States, Korea, Japan, India and the European Union, all united in their mission to understand and solve the problems driving global drug shortages. Participants from the United States government included representatives from the White House, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. Department of State.

According to the World Health Organization, the number of pharmaceutical molecules reported to be in shortage in two or more countries has doubled since 2021. Most of these molecules are key components of frequently-prescribed generic drugs, which puts pharmacists and physicians in the impossible predicament of caring for patients without sufficient supply of essential medications.

“Pharmacists are on the front line of the drug shortage crisis,” said Best, who partnered with White House staff to facilitate the event. “From struggling to keep drugs on hospital shelves to deciding how to distribute drugs in limited supply, we experience these shortages from every angle.”

“Drug shortages can feel intractable because there are multiple sources of the issue that span several countries. However, one of the overarching conclusions of the meeting was that there are actions we can take today to solve drug shortages, so there was a common sense of hope in the room.” - Brookie Best

Drug supply chains are fragile for a variety of reasons. These include the need for many ingredients, sometimes hundreds, to manufacture even one drug; lack of innovation in drug manufacturing, which still relies on slow, laborious techniques developed decades ago; and a lack of transparency in the pharmaceutical industry about how key ingredients and starting materials are sourced, which makes it harder to predict and mitigate future shortages.

Despite the frailty of pharmaceutical supply chains, the price-driven nature of the industry does not incentivize companies to build resilience into these systems.

From left to right: Ronald T. Piervincenzi, CEO of US Pharmacopeia; Robert Califf, United States commissioner of food and drugs; John Carethers, Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences at UC San Diego, Corinne Peek-Asa, Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation at UC San Diego, and Brookie Best, dean of Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Drug shortages in the clinic

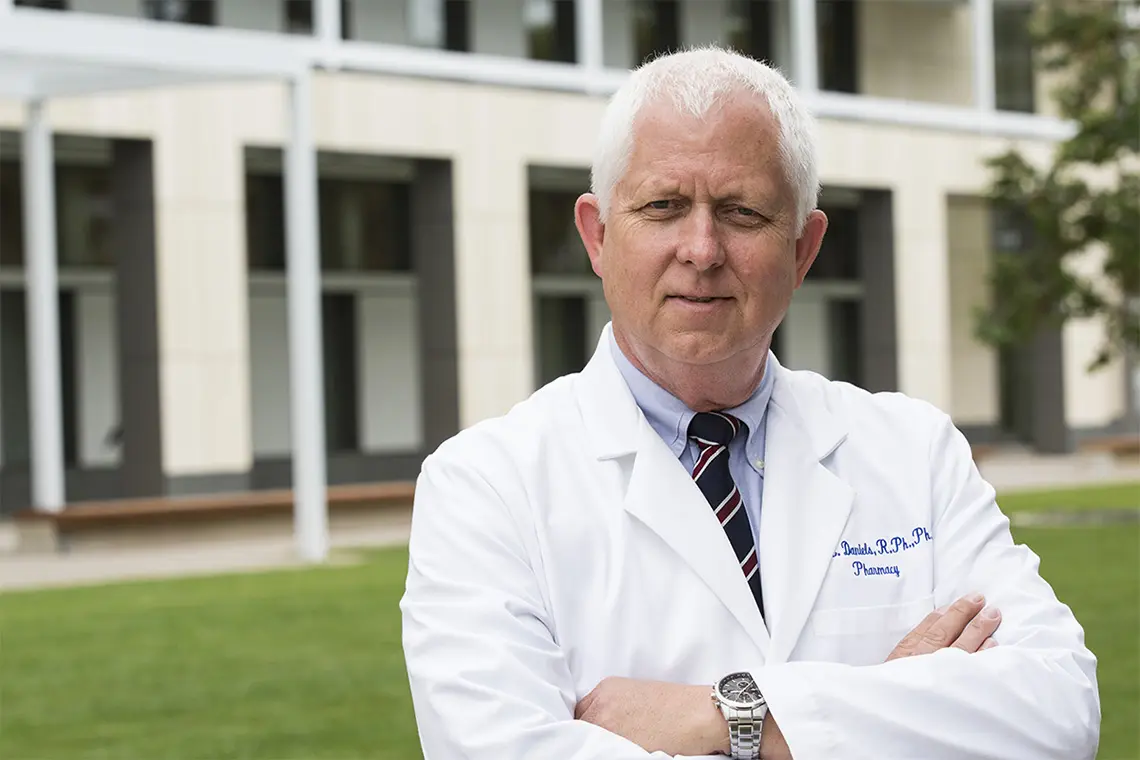

Charles E. Daniels, Ph.D., associate dean at the pharmacy school and chief pharmacy officer at UC San Diego Health, knows firsthand how disruptions to pharmaceutical supply chains can impact the clinical setting.

“Nationwide, there are hundreds of drugs in shortage on any given day, and this can have devastating consequences, even preventing us from curing diseases that we otherwise could,” he said, referring to vinblastine, a chemotherapy drug that can be used with other therapies to cure Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Recent and ongoing shortages of vinblastine have forced pharmacists and healthcare providers to make difficult decisions about how to conserve the drug.

Supply chain disruptions can also affect the most basic supplies required for medical care, such as saline, a sterilized salt water solution required for virtually all hospitalized patients. Saline went into short supply in 2022 due to increased demand for the solution during the pandemic, and manufacturers continue to report shortages of saline products today.

While shortages can be triggered by unpredictable events, such as natural disasters or armed conflicts, Daniels believes that strategies can be implemented to prevent and respond to them. He has also made recommendations to the United States Congress to this effect.

“To mitigate the impact of drug shortages, we need to diversify our supply chain by identifying new international partners and incentivizing manufacturers to invest in their facilities. This would help ensure a more stable and sustainable supply of critical medications,” he said. “Another crucial step is to develop contingency plans that can be quickly activated when a shortage occurs. This would enable us to respond more effectively and minimize the disruption to patient care.”

Engineering resilience in drug supply chains

One way to diversify and safeguard the supply chain is to develop new and innovative ways to create key starting materials for drugs. UC San Diego is a proven powerhouse in this space, and one of the highlights of the Bio-5 meeting was a tour of two laboratories in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering and the Shu Chien-Gene Lay Department of Bioengineering at Jacobs School of Engineering.

“Pharmacy researchers do the basic discovery research that drives new treatments, but there’s a need to connect that work with the technological innovations required to bring these drugs to market and produce them at scale,” said Best. “Engineering bridges that gap.”

Liangfang Zhang, chair of the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering, gave a brief introduction before the lab tours.

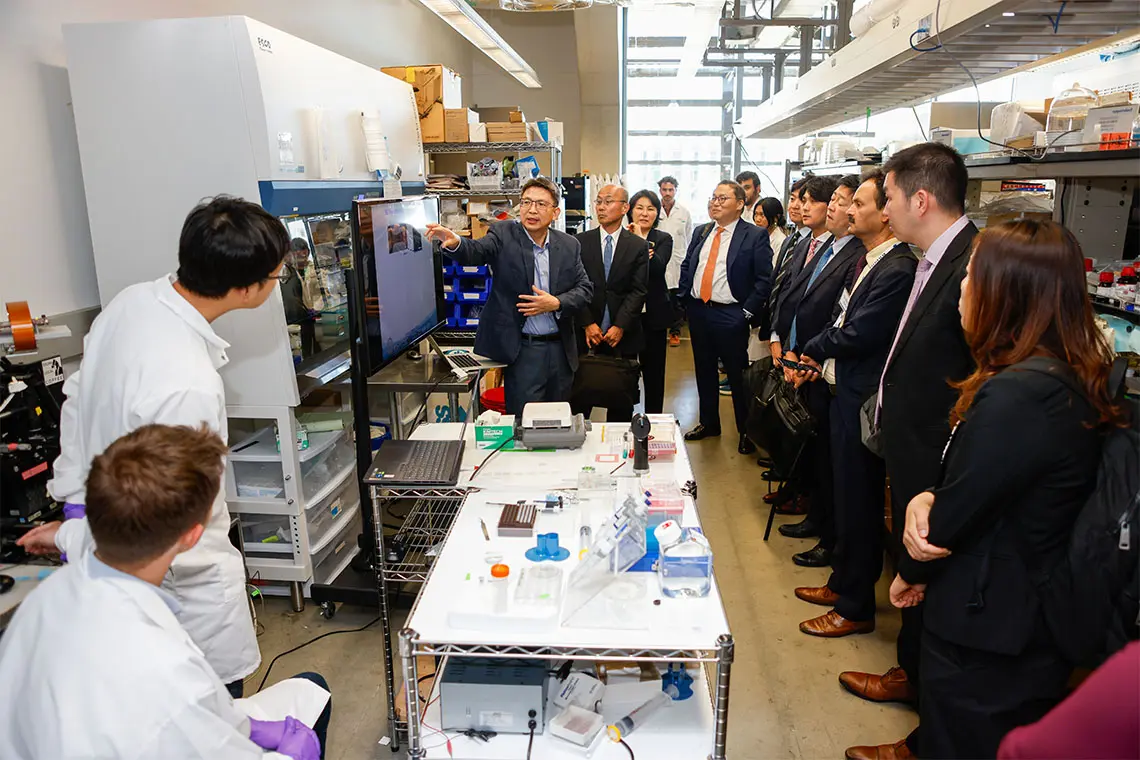

Shaochen Chen explains his lab's approach to 3-D bioprinting.

The group first toured the lab of Shaochen Chen, Ph.D., a nanoengineering and bioengineering professor who is developing new ways to print living tissues and organs by encapsulating cells in a 3D hydrogel. This type of 3D bioprinting technique can create biomimetic living tissues to repair damaged organs, study disease mechanisms, and test new drugs for toxicity and efficacy.

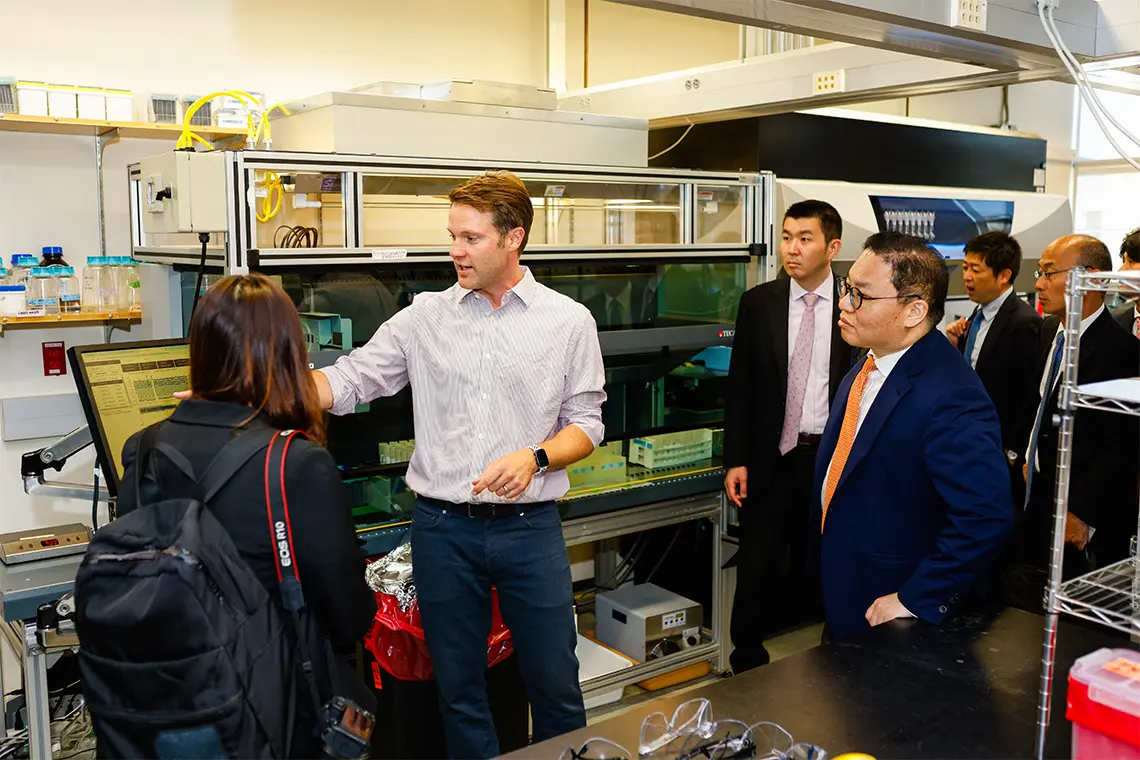

Later, the group toured the lab of bioengineering and pediatrics professor Bernhard Palsson, Ph.D., and research scientist Adam Feist, Ph.D. One of the focuses of the lab is adaptive laboratory evolution, a robotics-driven technology developed at UC San Diego that allows researchers to leverage the process of evolution to rapidly improve the metabolic efficiency of microorganisms that have been designed and engineered to produce specific molecules, effectively using them as miniature factories.

Adam Feist (second from right) and Bernhard Palsson (right) provide the group with a brief overview of their lab's capabilities before the tour.

The way ahead

While technological development, updated industry practices and policy changes will all play key roles in addressing the global crisis of drug shortages, Bio-5 has already made an optimistic start by uniting in the face of these challenges, according to Best.

“Drug shortages can feel intractable because there are multiple sources of the issue that span several countries,” she said. “However, one of the overarching conclusions of the meeting was that there are actions we can take today to solve drug shortages, so there was a common sense of hope in the room.”

Share This:

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.