Published Date

New Science Behind Algae-based Flip-flops

Biodegradable shoes meet commercial standards for products needed to help eradicate tons of plastic waste

Commerical-quality biodegradable flip-flops. Photo courtesy of Stephen Mayfield, UC San Diego.

As the world’s most popular shoe, flip-flops account for a troubling percentage of plastic waste that ends up in landfills, on seashores and in our oceans. Scientists at the University of California San Diego have spent years working to resolve this problem, and now they have taken a step further toward accomplishing this mission.

Sticking with their chemistry, the team of researchers formulated polyurethane foams, made from algae oil, to meet commercial specifications for midsole shoes and the foot-bed of flip-flops. The results of their study are published in Bioresource Technology Reports and describe the team’s successful development of these sustainable, consumer-ready and biodegradable materials.

The research was a collaboration between UC San Diego and startup company Algenesis Materials—a materials science and technology company. The project was co-led by graduate student Natasha Gunawan from the labs of professors Michael Burkart (Division of Physical Sciences) and Stephen Mayfield (Division of Biological Sciences), and by Marissa Tessman from Algenesis. It is the latest in a series of recent research publications that collectively, according to Burkart, offer a complete solution to the plastics problem—at least for polyurethanes.

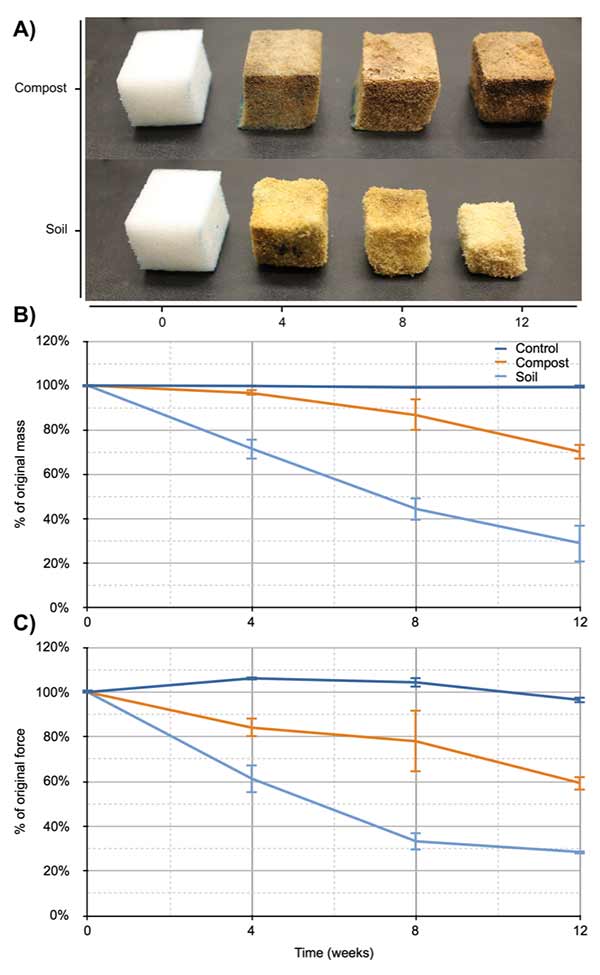

Biodegradation of PU cubes over 12 weeks. Degradation was analyzed through A) Change in appearance, B) Cube mass and C) Maximum force at 50% compression force deflection (CFD). Error bars indicate sample standard deviations of the triplicate measurements. For compost and soil mass loss, p<0.01 and for compost and soil CFD, p<0.01 (Table 2 in published paper). Image courtesy of Stephen Mayfield, UC San Diego

“The paper shows that we have commercial-quality foams that biodegrade in the natural environment,” said Mayfield. “After hundreds of formulations, we finally achieved one that met commercial specifications. These foams are 52 percent biocontent—eventually we’ll get to 100 percent.”

In addition to devising the right formulation for the commercial-quality foams, the researchers worked with Algenesis to not only make the shoes, but to degrade them as well. Mayfield noted that scientists have shown that commercial products like polyesters, bioplastics (PLA) and fossil-fuel plastics (PET) can biodegrade, but only in the context of lab tests or industrial composting.

“We redeveloped polyurethanes with bio-based monomers from scratch to meet the high material specifications for shoes, while keeping the chemistry suitable, in theory, so the shoes would be able to biodegrade,” Mayfield explained.

Putting their customized foams to the test by immersing them in traditional compost and soil, the team discovered the materials degraded after just 16 weeks. During the decomposition period, to account for any toxicity, a team of scientists led by UC San Diego’s Skip Pomeroy measured every molecule shed from the biodegradable materials. They also identified the organisms that degraded the foams.

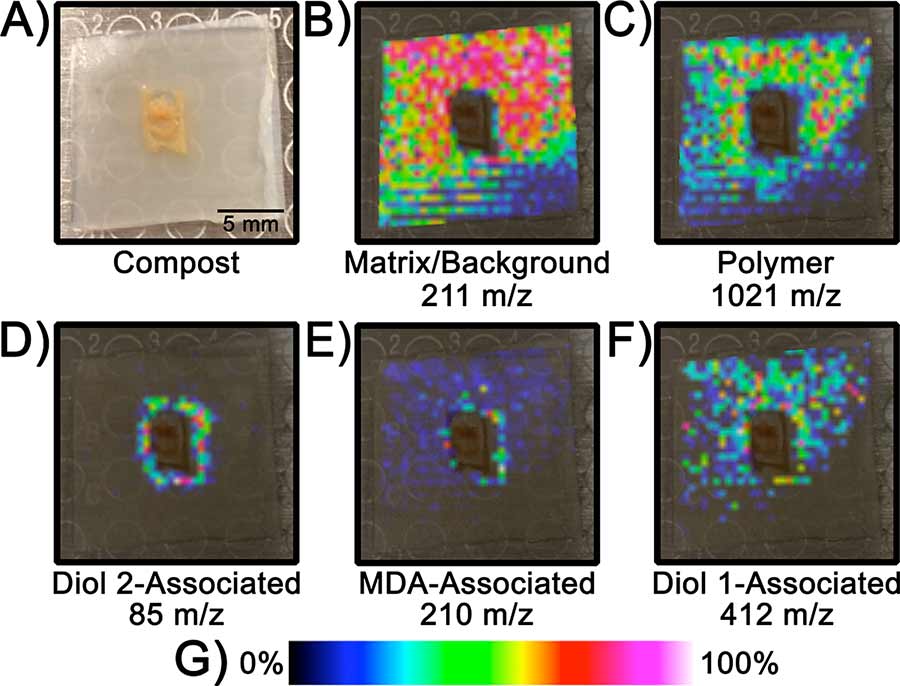

“We took the enzymes from the organisms degrading the foams and showed that we could use them to depolymerize these polyurethane products, and then identified the intermediate steps that take place in the process,” said Mayfield. “We then showed that we could isolate the depolymerized products and use those to synthesize new polyurethane monomers, completing a ‘bioloop.’”

Foot-bed of flip-flops being pulled from a mold. Photo courtesy of Stephen Mayfield, UC San Diego.

This full recyclability of commercial products is the next step in the scientist’s ongoing mission to address the current production and waste management problems we face with plastics—which if not addressed, will result in 13 billion metric tons of plastic in landfills or the natural environment by 2050. According to Pomeroy, this environmentally unfriendly practice began about 60 years ago with the development of plastics.

“If you could turn back the clock and re-envision how you could make the petroleum polymer industry, would you do it the same today that we did it years ago? There’s a bunch of plastic floating in every ocean on this planet that suggests we shouldn’t have done it that way,” noted Pomeroy.

While commercially on track for production, doing so economically is a matter of scale that the scientists are working out with their manufacturing partners.

“People are coming around on plastic ocean pollution and starting to demand products that can address what has become an environmental disaster,” said Tom Cooke, president of Algenesis. “We happen to be at the right place at the right time.”

IMS of compost-derived organisms growing on PUM9 film-agar plates. A) Photograph of the culture growth one week after incubation, with scale bar for all images. B–F) Mass distributions indicating location and relative intensity of the given m/z value and its molecular association. G) Relative intensity scale for B–F. See Supplementary Data for evidence of molecular assignments. Image courtesy of Stephen Mayfield, UC San Diego.

The team’s efforts are also manifested in the establishment of the Center for Renewable Materials at UC San Diego. Begun by Burkart, Mayfield, Pomeroy and their co-founders Brian Palenik (Scripps Institution of Oceanography) and Larissa Podust (Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences), the center focuses on three major goals: the development of renewable and sustainable monomers made from algae and other biological sources; their formulation into polymers for diverse applications, the creation of synthetic biology platforms for the production of monomers and crosslinking components; and the development and understanding of biodegradation of renewable polymers.

“The life of material should be proportional to the life of the product,” said Mayfield. “We don’t need material that sits around for 500 years on a product that you will only use for a year or two.”

In addition to Gunawan, Burkart, Pomeroy and Mayfield, coauthors of the Bioresource Technology Reports paper include Tessman, Ariel Schreiman (Division of Biological Sciences), Ryan Simkovsky (Division of Biological Sciences), Anton Samoylov (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry), Nitin Neelakantan (Algenesis Materials Inc.) and Troy Bemis (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry).

The research was supported by grants from the Department of Energy Bioenergy Technologies Office (DE-SC0019986) and the National Science Foundation (1926937) to Algenesis Materials.

Burkart, Mayfield and Pomeroy are all co-founders of Algenesis and have equity. In addition, Burkart and Pomeroy are scientific advisors and Mayfield is acting CEO and on the Board of Directors.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.